What Lasts

Writing after the fires

This week, I was going to bring you my latest Q&A with Kevin Nguyen, features editor of The Verge, but I have only been able to think about the fires, the victims, and all that is gone.

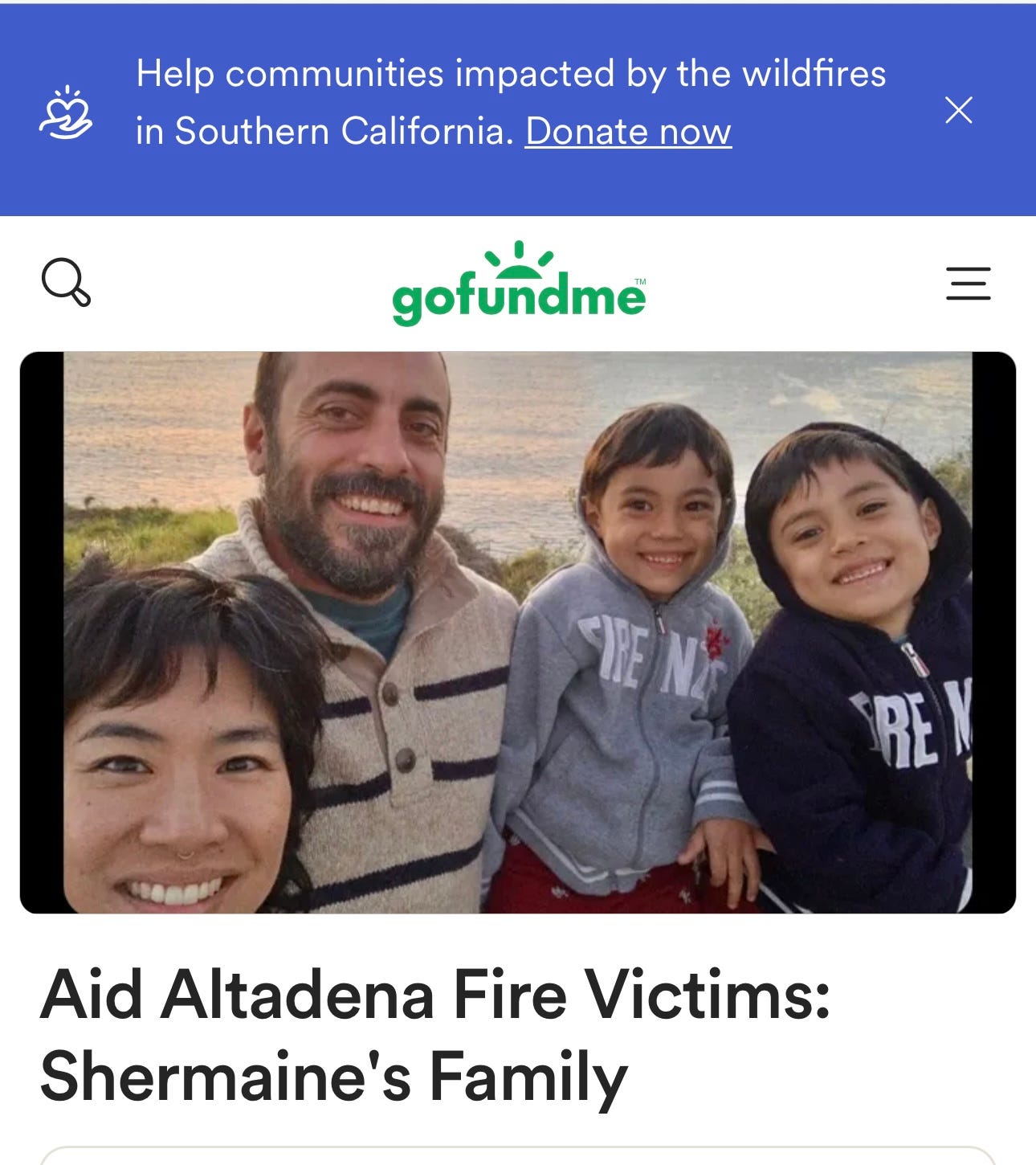

If you live in the Los Angeles area, you likely know someone who lost a home. Like my dear friend of two decades, Shermaine, who in 2012 stayed up all night making tissue paper pom-pom decorations as a last-minute surprise for my DIY wedding. Shermaine also married, and moved to Altadena (near my then-rental in Eagle Rock), giving birth to identical twin boys.

One afternoon in 2015 she visited me, balancing both babies and nursing them simultaneously. I marveled at her mothering and shook my head: I could never.

A couple of months later, I found out I was pregnant—also with identical twin boys. I cried at the ultrasound, shocked and unsure if my husband and I could manage. But Shermaine was there, 10 minutes away, proof it was possible. She passed on advice and hand-me-down twin clothes. Our boys got bigger, year by year.

Last week, Shermaine and her family evacuated in the Altadena firestorm at 3 a.m., as their home—a haven where her twins took their first steps—burned to nothingness. Her family now has a GoFundMe, which you can also find on this list of displaced Filipino residents (Shermaine and her family initially fled to her brother-in-law’s home, but the fire soon destroyed his house too).

So many in Altadena are working-class, everyday folks. Here are other resources to donate directly to displaced survivors, including Black, Latino, and disabled families and residents.

“I had only ever lived in apartments my whole life,” Shermaine wrote on Instagram in a tribute to their home, her first owned house, “where the twins’ doorjamb, marked biannually since the age of two, now rests as a pile of ashes.” Today, her twins turn 9.

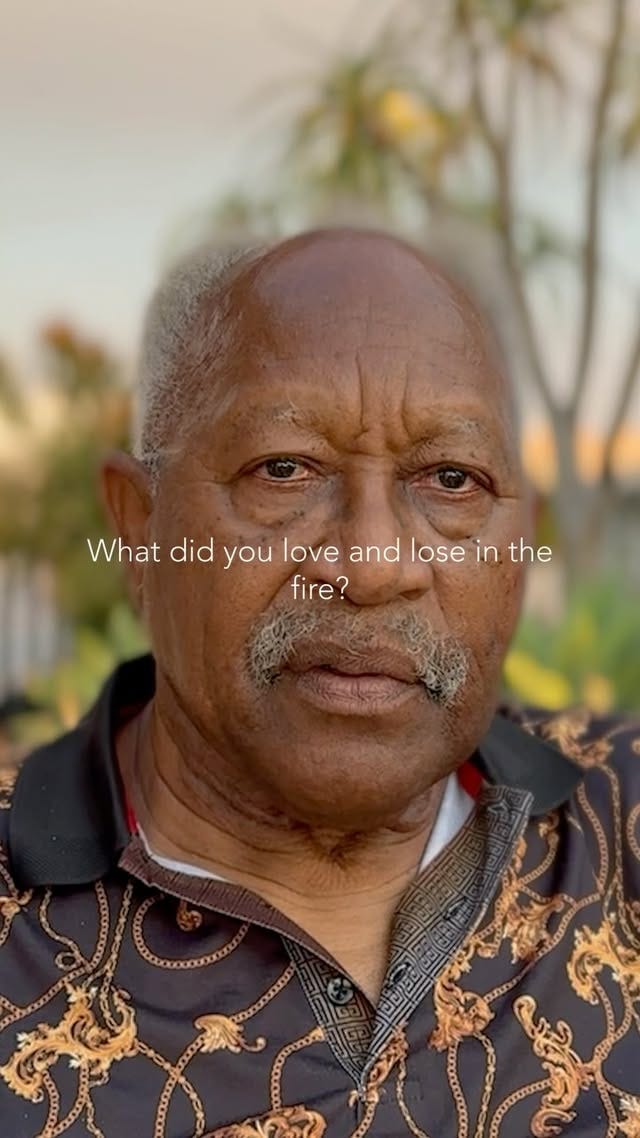

There are too many stories like this. My longtime mentor, Richard Kipling, who hired me as part of the Minority Editorial Training Program at the Los Angeles Times when I was 21 (and who was one of the first generous paid subscribers to this newsletter) also lost his Altadena home.

Four months ago, Richard turned 80. Fellow graduates of that training program from across the country gathered in Los Angeles to surprise him, and honor his legacy. Richard took a chance on us, believed in our talent, and taught us the power of storytelling. Last week, he shared his own fire story on Facebook: “Only 3 houses out of the nearly 30 on the block survived.” (If you read this, Richard, my heart is with you.)

I don’t know what will happen to the Los Angeles area next. But I do know there will be stories.

This vast region of Southern California is rich with storytellers. You will find them on the hillsides and flatlands, in rentals and historic homes, in the mountains and beaches, on campuses and street corners, inland and in the OC. People who grew up here, or perhaps ended up here because they process their ideas and questions about the world through their craft.

Among those I know who have been impacted (in Altadena alone), there are poets, journalists, essayists, editors, screenwriters, authors, bloggers, creators. When they are ready, I know many will tell stories that will move us and make us try to do better the next time this happens.

Stories That Endure

National coverage of any climate catastrophe, and any big disaster, always arrives in waves. First, the aerial shots. Drone footage surveying the devastation, as we gasp at the images of coastlines and neighborhoods destroyed. There will be many of these wide-lens views, until the shock wears off, and we numb to it all.

There will be plenty of birds-eye-view writing, too—sweeping rundowns of damages, loss, destruction, and assessments of what is left. Heavy with stats, officials, experts. In these articles, the writer’s camera will hover above the scenes of the charred landscapes, barely getting close to skin.

But I will be here to read and listen to the human stories from people on the ground. Already, some of these poignant first-person pieces have emerged in our media ecosystem. Like this one from my former colleague, James Rainey, who embarked upon a journey to see if his childhood home was still standing. He makes us wait, and does not reveal what he finds until the end.

Rainey drives to Malibu, taking us on a journey into his memories, visceral and specific: wildflower honey, a Hungarian sheep dog named Zala, woodcut prints, the occasional leopard shark. What I love, and will remember in particular from this story penned on a daily deadline, is how he reveals himself also as someone who has at times grappled with who he is:

“This isn’t just a hometown love note. I had been so ambivalent about being from Malibu that I tended to fudge when asked where I grew up. I’d say “the Westside of L.A.” Or “I went to Santa Monica High.” Both true, but not the full answer.”

How many of us have at some point felt boxed in or categorized by where we are from? It is a tiny personal detail that is also universal. We may not have lost anything in this fire, but we see you.

Micro-narratives are all around us right now. Escapes and returns. How will they end up? On Instagram, we hold our breath as a family drives through ruins, citing their neighbors’ names, until they arrive at their own home, which is, incredibly, still standing. It closes with a cry: “Thank you, Jesus.”

Filmmaker Kalina Silverman seeks to have meaningful conversations with strangers, and if you listen to her recent interviews, these are not just “fire victims,” a trap that storytellers can easily fall into. They are multidimensional people who talk about growing up and having holes in their shoes when it rained, or falling in love on a dance floor at 17. She asks questions that draw out details that humanize them, and depict them as so much more than their trauma. We picture their daily lives before. Like in Rainey’s piece, these particulars connect us.

The national news will move on. This will be the next wave. Big outlets will return for updates and anniversaries, while devoted local reporters will continue covering the lives lost, steps to rebuilding, investigations, lawsuits, survivors forgotten or left behind in this disaster’s wake.

But the camera lens will always eventually pull away. After all, there will be so many more climate-related catastrophes to contend with.

During the last academic quarter, my student struggled to keep up in classes as she realized her hometown of Asheville, North Carolina, had been smeared away in horrific floods. She wanted to write about this place where she grew up, where her parents somehow survived the hurricane and floods, but others did not.

She booked a plane ticket and packed audio recording gear. Before she left, she worried. National reporters had cleared out weeks earlier. Social media had shifted its lens too. “The news has moved on,” she said. Would anyone even care?

“That,” I told her, “is exactly why you are telling this story.” Meaning can come with time, discovered when others no longer seem to be looking for it. This is the storytelling that ripples after the waves.

What made her perspective so valuable was her connection to Asheville combined with her ability to record, ask questions, and write. She was not parachuting into an unfamiliar place. She knew the people, the roads, and the landmarks as closely as the contours of her own childhood memories. They are entwined, and she brought this close-up point of view into her interviews and storytelling.

As many of you know, I spent last year reporting on the aftermath of the wildfires on Maui. I know it is not easy to publish these pieces. Yes, there will be a slew of LA fire stories. Still, maybe you are from here, and you have an unexplored connection to these fires that you want to write about, but you do not have access to outlets, editors, or publishers. If so—even if it is months or years from now—please DM me or send an email reply to this newsletter, and I will try to connect you to the right ones. If the fires touched your life, and you see a story and don’t know what to do with it, or if you want to bounce off a pitch, don’t be afraid to reach out.

In my chat with Nguyen from The Verge (which I will post next week) we talked, before the fires, about stories that last. The kind of writing that, as he puts it, will “be read many years from now.” Nguyen added: “Sometimes, if you’re lucky, it is quite a moving piece of writing. You want it to be enduring in the sense that it stays with people.” We won’t remember the whole story. Sometimes, what stays with people is simply a specific detail, a person, a quote. It might be a moment, or a feeling.

Fourteen Tips for Telling Stories That Hit Home

The next disaster might arrive in our own backyard. When the time comes to write something, here is what I offer as advice, which I also share with my students:

What do you see that others don’t? How have your own life experiences—the way you move through the world, your vantage point, your concerns and curiosities—helped you spot an angle that others miss?

Who are the experts with lived experience?

Reporters don’t be afraid to include yourself, when the story calls for it.

First-person or memoir writers, don’t be afraid to report, when the story calls for it.

Always check the clips. What has already been written? Can you offer something more? Something overlooked? Something that lasts?

Narrow the frame. Consider one house. One building. One block. One family. One journey. One object. One relationship. One day. One hour. One year.

It is okay to let it unfold.

Zoom your lens in tight. Pay attention to the emotions, details, moments and connective points that will resonate with someone who is not living this story.

Look for a natural intersection, and lean in. Psychology, history, philosophy, literature, art, technology, labor, science. The unexpected connections that you instinctively see.

Consider archives. Building planning records, city reports, fundings streams, oral histories, newspaper clips, archeology, internet trails.

It is okay to toggle.

Talk to people. Ask thoughtful questions. Listen. Bear witness.

Don’t turn victims into their trauma. Humanize people, and practice trauma-informed reporting.

Consider the social and existential questions that have always haunted you. Ask yourself how do they manifest in this moment, right now? What might they reveal tomorrow? What will remain when all else passes?

It’s essential to always bear witness, even when others have turned away. Thank you so much for reminding us we all have a responsibility to remember.

Erika I read this twice. It’s instructive storytelling advice, and powerful emotionally, rich with humanity and meaning. Thank you.