Recently, I dropped into the Journalism Group at The Writers Grotto via Zoom to discuss my year of freelance reporting on the Maui wildfires, which I have also detailed below. Started by freelance journalist Katia Savchuk, the Journalism Group is a place for freelancers and other journalists to check in with each other and participate in Q&As.

Over a one-year period, I submitted 20 pitches and two grant proposals to write stories on the aftermath of the deadliest U.S. wildfire in over a century. Thirteen of my pitches were either ignored or rejected by editors. I did not receive either grant.

In the end, however, I did publish seven Maui fire-related stories between January and August of this year. Three are longform, at around 6,000 to 7,000 words. The other four pieces range from 1,500 to 2,500 words each. I have also submitted my rates with The Freelance Solidarity Project’s Rate-Sharing Database.

I am sharing the behind-the-scenes story of my reporting with you because I realize that more than a third of working journalists are now freelancers. At least 8,297 U.S. journalists have been laid off since 2022—nine percent of the 89,330 people employed as newspaper, broadcast, and online editors, reporters, and journalists, according to the Institute for Independent Journalists layoff survey covered by Katherine Reynolds Lewis in the Columbia Journalism Review.

I know this work is difficult, lonely and costly. When I first started freelancing, I had very few freelance friends. Now a decade into it, I rely on my writing communities to help me navigate a challenging industry. Creating regular check-in groups and writing circles for journalists working on longform projects, as Katia has done, can be a major support system in the freelance writing world.

Over the years, I have also been part of trusted longform journalism groups. Sharing a pitch, story draft, or a working chapter with other writers can be a vulnerable experience, so keeping it small (three to five people) is best if you are critiquing each other. Larger groups are also helpful, and can be more of a support system or an opportunity to share strategies.

The best way to find a group may be to start one yourself. Look around for writers who are doing the kind of work you admire and practice. Reach out to them. This webinar I participated in a couple of years ago on “How to Make Longform Journalism Work,” from the IIJ, grew out of one of these writer’s groups.

Why I Made Maui My Assignment

I live in California and remember well the in-depth narrative coverage on the Camp Fire in Paradise—from “We Have Fire Everywhere,” by Jon Mooallem in The New Times Magazine, to “Gone,” by Mark Arax in The California Sunday Magazine. Both cover stories ran eight months after the 2018 wildfire that took 85 lives.

It quickly became clear that Maui’s death toll and destruction would surpass that of Paradise’s. I thought of Hawaii’s colonial history and Maui’s victims, many of them Native Hawaiians, Filipinos, immigrants, workers in the tourist industry.

My friend, Portia, a photographer who has lived on Maui, invited me to join her on the island. She wanted more in-depth local stories told. She is fluent in Tagalog and some Ilocano, and could help with translation. She became a kind of interlocutor, as defined by

, who writes on anthropological methods in journalism.I am a professor of literary journalism, and teach during the school year. I am also a mother, so traveling to cover a story is never a simple or easy decision. But it was summer, and the timing also made a reporting trip possible.

Given the historical context of exploitation throughout Hawaii, and the working class victims who are often the most vulnerable and forgotten after a climate disaster, I agreed their stories deserved as much attention as Paradise, if not more. The storytelling had to be handled sensitively, using trauma-informed reporting. I also believed that narrative storytelling could best convey their experiences on a human level, not just as news headlines.

But I did not yet have an assignment when I booked my flight.

Airline Points

I thought I would write one story, focusing on a few subjects from Maui. I used my Delta airlines points on a plane ticket. Before I left, I sent three magazine pitches. One was rejected. One could not immediately commit. The third, sent to New York Magazine, led to an editor giving me a “green light” the day before I departed.

Before I left, I had already deeply interviewed two main subjects who would end up becoming the focus of the New York piece, “Maui on Fire.” I had connected to Lanz through TikTok. She and her girlfriend, Isabella, happened to be staying near me in Southern California, where they had fled to shortly after narrowly surviving the fires. We met in person. Lanz was planning to return to Maui to help her parents, who had lost their home. I also arranged to meet up with Lanz and her family on the island.

Edralina

On the plane to Maui, I overheard a passenger seated in the row in front of me talking to others. Her parents, both immigrants from the Philippines, had lost their home in the fires and were sheltering at a hotel in Lahaina. I did not want to bother her on the five-hour flight, and didn’t plan to even try.

But later, she ended up standing right next to me outside of the baggage claim while we waited for our rides, which were running late. I introduced myself as a journalist, explaining I overheard her conversation on the plane. She said her name was Jovi, and we exchanged phone numbers. The next day, Jovi texted me: “Hello Somebody here wanna share her story.”

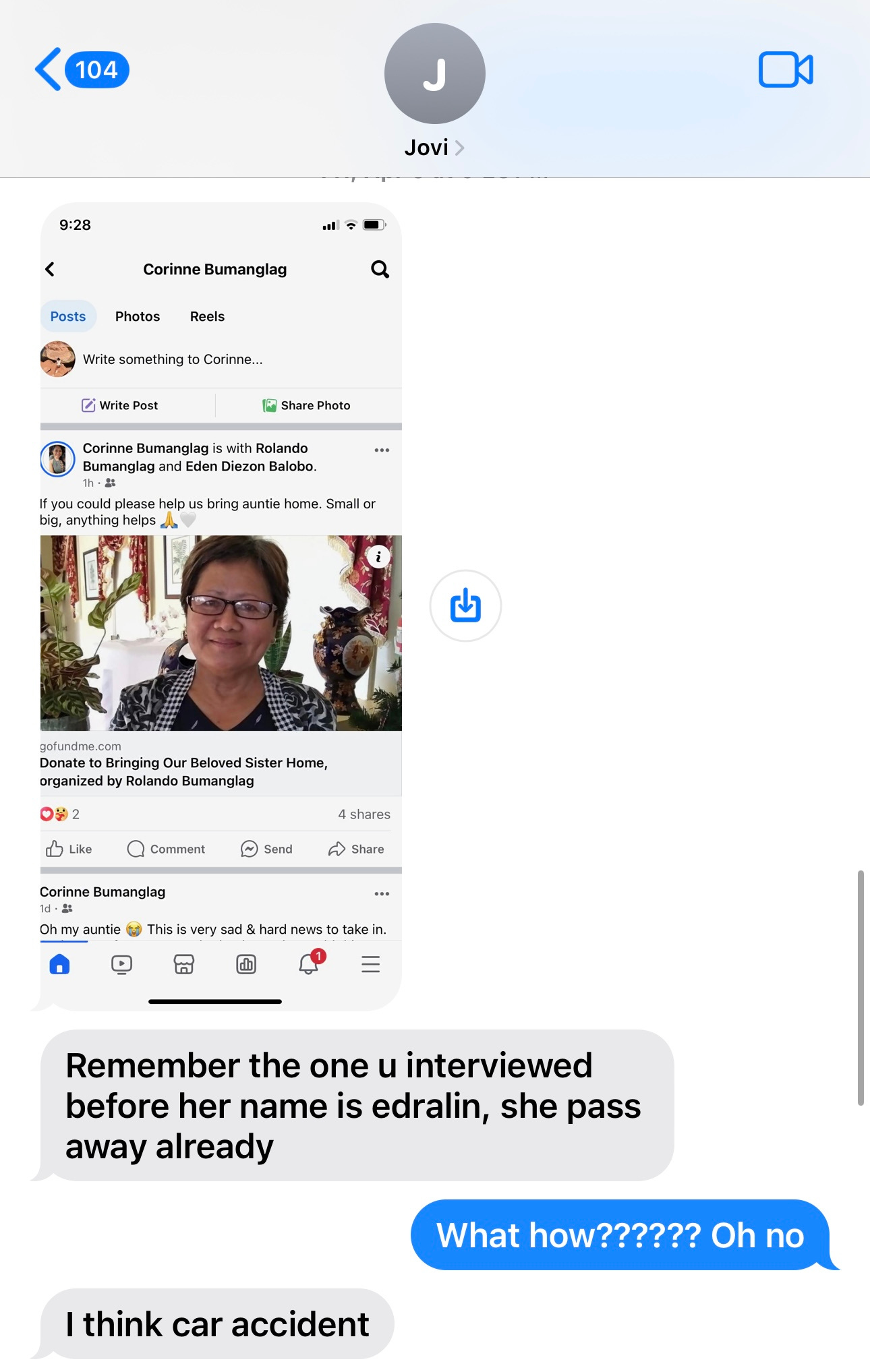

She sent me a photo of a woman, Edralina, who had lost her home and was staying at the same hotel as Jovi’s parents.

I spent the next week with Edralina, tagging along as she applied for funding, emergency services and went to work as a janitor at the Lahaina Gateway, even though everything around the mall had burned down.

I also met up with Lanz and her family in their Maui shelter hotel. And I got to know a half-dozen other survivors closely during my travels, sitting with them for hours, listening to their stories, checking in, and following up in the months after.

The love story of Lanz and Isabella, a narrative that also interrogated how and why so many people ended up trapped in the inferno, was published in New York’s January issue and online at The Cut. At 6,800 words, it involved reviewing hundreds of hours of 911 calls and police body camera footage obtained through public records requests.

But I still wanted to find a way to include the stories of the other people I met, like Edralina, who did not end up in that initial piece.

Separate Profiles

Upon returning from Maui, I secured two more magazine assignments, both from editors who reached out to me on their own during this time period, asking if I had story ideas.

“Is there anything you’re working on that may be a good fit?” wrote an editor for MIT Technology Review. I mentioned my reporting in Lahaina. She was interested in DNA technology, and I told her about a family I had encountered that went through the DNA matching process. We began working on the story, which ran in May.

I had previously sent a pitch to an editor from Men’s Health about a different Maui idea, but I never received a reply. A few months later another editor, also from Men’s Health, emailed me. She had recently moved over from Marie Claire, where I had published stories before. “I would love to discuss anything you may be thinking about that could be a fit for MH.”

I pitched her a piece on an unlikely hero from Lahaina named Kekoa, and the mental health crisis after climate disasters. The piece ran in the magazine in September.

I could have stopped at three. But there were other Maui-related stories left to tell, from people I had come to know.

Six months after my first trip, I traveled back to Maui to follow up with them. I used to be a national reporter for the Los Angeles Times, and now as a freelancer I approached Maui reporting as a national writer would—each story, though originating out of the same place and tragedy, had a significantly different in angle and scope, tackling climate migration, women, labor, the economy, science, housing, mental health, infrastructure, Native Hawaiian practices in land redevelopment.

I felt like each person I got to know deeply in Lahaina deserved their own profile, and each one’s story represented a different facet of the tragedy.

Rejections

I pitched an idea about housing shortages to another magazine editor who asked me to rewrite my story proposal twice—a task that took several weeks of going back and forth, and required additional unpaid reporting. Still, I received this rejection:

I’m sorry to tell you that the EIC has decided to pass on this story. I'm really so sorry the process took this long—I was pushing hard for it, but ultimately she was just looking for something different than what you're putting together.

Here is a sampling of my other rejections:

It’s great that you’ve built relationships with women in Lahaina. My impulse as a features editor is to let things unfold for a few beats so we can start to answer some of the Qs in your pitch.

The team decided to pass on this, but would love to work with you down the road.

Unfortunately I need to pass on this story as we already have in the works a long feature on Lahaina's recovery coming out in a few months.

The situation in Maui so discouraging. But folks decided this one is not quite right for us at this time.

I'm really into Hawaii's ugly colonial history generally, but I couldn't get any traction with the other editors unfortunately.

Multiple Pitches

I pitched three editors at The Guardian. Two of them never replied. The third, Frida Garza, whom I cold-pitched after watching her webinar via an IIJ conference, got back to me one month after I sent her a story idea. Her plate was full, but she passed the pitch onto another editor at The Guardian, who assigned me the piece.

It focused on a woman I met in a hotel on Maui who ended up moving to another climate-stricken city, Las Vegas, along with other Lahaina survivors. I traveled to Las Vegas to reunite with her.

I rarely send multiple pitches at once, but as the one-year anniversary of the wildfires approached, I felt like the remaining stories I had yet to tell were time sensitive and I could not wait months for editor replies before re-pitching. No one was hungry for me to write these pieces. At least six of my pitches never received any response at all. Seven were rejected, graciously.

Two more magazine editors passed, but then sent my pitches along to their web teams, resulting in shorter features for National Geographic and Elle.

A Tragic Turn

Along the way, as I was still pitching and reporting, I received a text message from Jovi, who alerted me to heartbreaking news: Edralina had been killed.

I knew that ever since the fires destroyed her neighborhood, Edralina had waited for rides along a busy highway in the dark to get back and forth from work to her hotel. I felt terrible that I had not yet been able to get her story published. Now, she was gone.

These are the moments that you feel especially guilty as a freelancer. If people have spent time with you and trusted you, yet you can’t publish the stories that you believe are important, you might ask yourself: What is the point of trying to do this work at all? I have had my share of such reckonings.

I began pitching with renewed urgency. At first, I included what happened to Edralina in a more sweeping pitch that included other survivors, in which I wrote to an editor:

“When people think of climate disasters, they often forget that the people who survive the event itself might lose still their livelihoods or even their lives in months or years after, from the fallout and suffering related to the initial tragedy.”

He sent back a rejection. But he also added a piece of advice:

“I do think that the kernel of an idea you identified with Edralina is most intriguing...the idea of the hidden death toll.”

I took that advice, rewrote my pitch to focus solely on Edralina, and pitched it to an editor at The New York Times. He assigned me the story.

When I returned to Lahaina, I interviewed Edralina’s co-workers and retraced her final steps. Edralina was the first person I interviewed while on Maui, and her story was the last pitch to be accepted.

Sometimes as writers it seems like we are guided to stories by our instincts and the people and issues we care about or feel drawn to. This also makes it harder to let go if you can’t get your ideas off the ground.

I have been freelancing long enough to try not to take rejections personally. I know editors are under tremendous pressure. They often have to seek final approval from other editors, who may have their own priorities. Sometimes this involves the editor presenting your pitch in front of their colleagues at an editorial meeting. Budgets are slim. Space is tight. Editors are overworked. They have to field tons of pitches while also juggling meetings, editing stories, their own lives.

Editors are also regularly laid off. In fact, at least two of the editors I pitched were laid off not long after I sent them my Maui ideas. Others barely managed to hang onto their jobs, as layoffs ensued all around them. They may have kept their editing positions, but they also inherited heavier work loads.

These days, if I really believe in a story idea that is just not getting any love, I give myself time to rethink, revamp, and keep trying. I do also realize that sometimes we have to move on.

This time, though, I just couldn’t.

The pitching and rejection cycle can be so lonely, and pieces like this make it just a little less so. Thank you Erica!

Learning from your detailing the behind-the-scenes process of getting a story told is what I appreciate about your substack so much. This post shares so much about your persistence and your drive. I know of a couple of journalists who want to tell stories about L.A. after the wildfires, and I hope to impart your wisdom to them from this post and another about why their local stories will continue to matter. The first photo of Edralina in this piece breaks my heart, knowing what happened to her the year following. Thank you for shedding light on what the toll has been for survivors.