'Truth Before Everything'

Haley Cohen Gilliland on the Ethics & Challenges of Reconstructing the Past

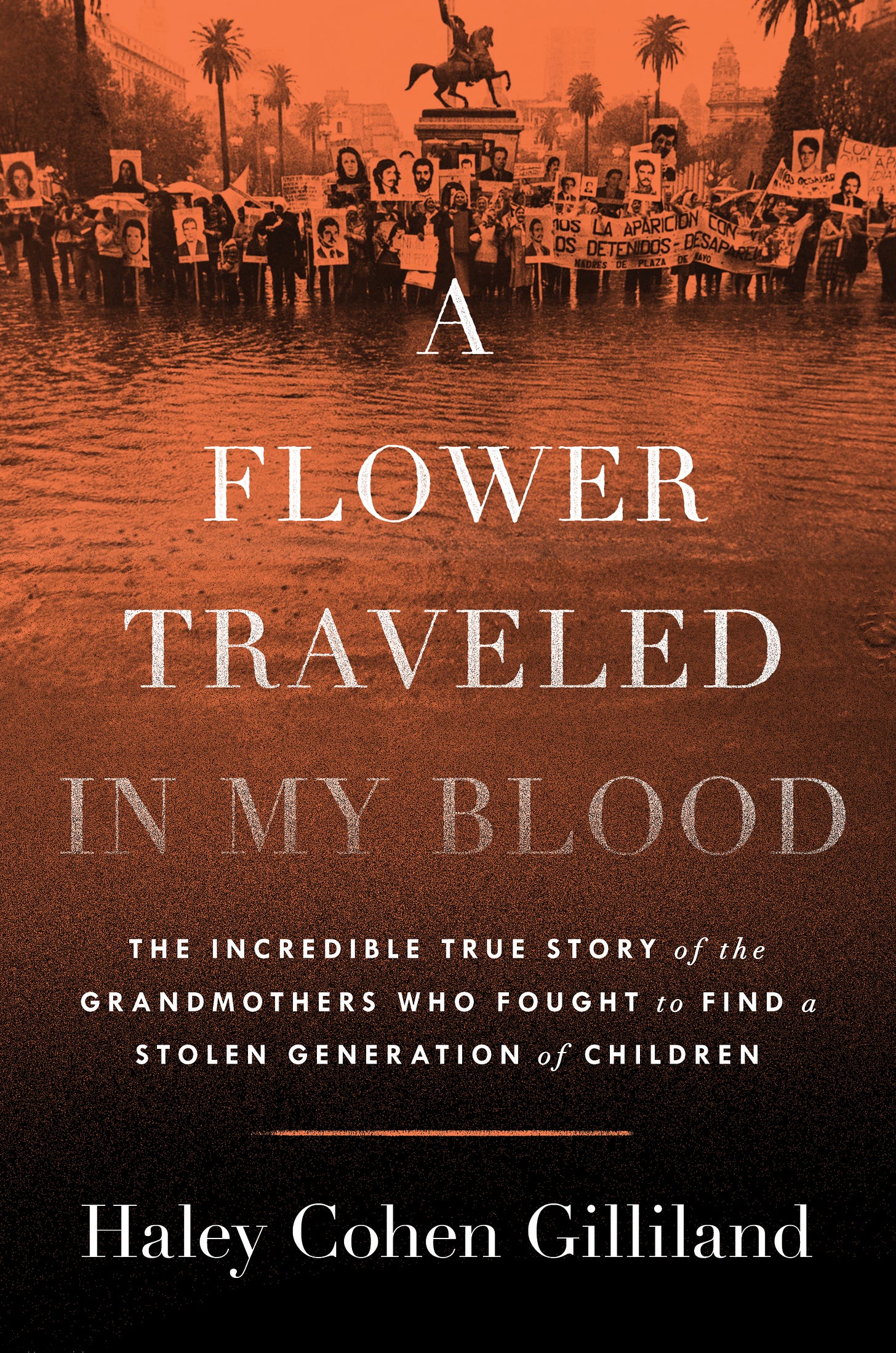

The beginning of Haley Cohen Gilliland’s gripping new narrative nonfiction book, “A Flower Traveled in My Blood,” begins in media res, with a terrifying 1978 kidnapping inside of a toy store:

“The men crept in so quietly she didn’t notice them at first. They moved fast, too fast for her to remember if there were two or three, or to see their faces.”

From there, a nightmarish scene unfolds against the backdrop of Christmas decorations—nativity scenes, shimmering green tinsel, Santa ornaments. Men in beige raincoats capture the shop owner, a young father. Later, they snatch his pregnant partner, who will end up giving birth to their son in captivity. The abducted couple also leaves behind a toddler named Mariana, who howls as her parents vanish: “Papá, Papá.”

Haley’s meticulous reporting illuminates the story of a group of grandmothers who devoted their lives to finding their grandchildren, stolen under Argentina’s right-wing military dictatorship. She carefully braids history and science into the narrative, as the grandmothers work with an American scientist on breakthrough DNA sequencing.

The book also zooms in close to follow the lives of one family ripped apart in the country’s Dirty War, during which thousands of people were tortured, murdered, and disappeared. This kind of intimate lens usually requires building trust and access to main subjects, and Haley’s reporting raises important questions for nonfiction writers: What if key members of the family don’t want to give interviews, or are not physically able to?

The Author’s Note as a Lesson

I often find author’s notes by nonfiction writers to be instructive and illuminating, and Haley’s reveals that Mariana (who would grow up in the shadow of this traumatic history) declined to participate in the book.

Yet Haley got to know Mariana’s brother, Guillermo, born in a torture center and raised by a military couple. He was open to sharing. As adults, Guillermo and Mariana became estranged. Haley moved forward with the book project about the family, but worried her reporting could stir up tensions between them. Guillermo became a main subject, but she also relied on Mariana’s own public writing to reconstruct some details of her life and story.

At the heart of the book is Mariana and Guillermo’s courageous grandmother, Rosa Roisinblit. Last week, Rosa died at 106. “A Flower Traveled in My Blood” chronicles Rosa’s bravery in the face of brutal repression. But during the reporting, another major complication arose: Haley only met Rosa once, in November 2021, before she moved into an assisted living home.

Haley writes in her author’s note:

“When I asked if I could go see her there, Guillermo said she was not in a condition to give interviews, adding: ‘She’s done enough already.’ As much as I wanted to speak with Rosa again, I didn’t feel it would be ethical to push—and I wasn’t sure how much doing so would accomplish.”

Given that the book’s narrative reconstruction, interiority, character development, and scenes are so vivid and close-up, including with Rosa and Mariana, it is remarkable to realize that Haley did not have full access to two of the main family members depicted. This is Haley’s first book, and it’s a powerful example of narrative reconstruction that also employs trauma-informed sensitivity and techniques of the write-around.

In today’s Q&A, Haley talks about how she managed to richly render her subjects—even when she couldn’t always conduct direct interviews with everyone involved herself. To pull it off, Haley studied blogs, oral histories, photos, court documents, news archives, autobiographies and more to construct visceral scenes like toy store kidnapping.

I have such admiration for Haley, and I’m delighted to bring you our conversation. Several years ago, we were part of a longform writing group in Los Angeles, back when she was still polishing her book proposal. I remember being astounded by how long and in-depth her proposal was (a process she also talks about in today’s chat). I appreciated her candor and teaching spirit, and I hope you will too.

One Year at The Reported Essay

This month marks one year since my first post at The Reported Essay. Since starting this newsletter about narrative writing, longform, and freelancing, I am grateful to all of you who have subscribed, and also blown away by the exceptional writers, editors, and agents I’ve encountered on Substack who are sharing their own knowledge and expertise. You can really construct your own nonfiction graduate degree-level syllabus by studying some of these folks and subscribing to their newsletters.

In the last few weeks alone, Creative Nonfiction Founder Lee Gutkind interviewed journalist Jeanne Marie Laskas for

. Alexander Chee wrote a wonderful lesson on description and setting. Meghan O’Rourke offered thoughts on revising a personal essay, and Brandon Taylor gave advice on editing vs. revising. Meanwhile, Christian Elliott at The Science Reporter's Cut is regularly posting behind-the-scenes lessons from the life of a freelancer.I’m also excited for these newly launched or revived newsletters: The Waterproof Notebook by Kim Cross; Baby Monster Story Machine by Chloé Cooper Jones; The Flame by Prachi Gupta; Word On A Wing by Moni Basu; Travels with Mona Gable; and Brendan O’Meara’s Pitch Club.

Haley Cohen Gilliland

Haley is a fellow writer who values mentoring and the sharing of craft and career knowledge. As the director of the Yale Journalism Initiative, she also works closely with students.

Previously, Haley worked at The Economist for seven years, four of which were spent in Buenos Aires as the paper’s Argentina correspondent. Following her time at The Economist, she has focused on narrative nonfiction—bringing history and current events to life through fact-based storytelling. She has published longform features in The New York Times, National Geographic, Bloomberg Businessweek, and Vanity Fair, among other publications. She lives in New York state with her husband, two children, and dogs.

Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

You mentioned in your book being a recent graduate living in Argentina doing a fellowship. You came across an article about the Argentine military abducting pregnant women and stealing their babies. Were you already thinking about this story as a journalist at that point, and as a narrative writer?

I have always gravitated toward writing. In high school, there was one journalism class I really enjoyed, but most of the curriculum was geared toward literature and fiction. I didn’t get much exposure to nonfiction, especially narrative nonfiction. It wasn’t until college, when I started writing for a magazine modeled after The New Yorker, which was called The New Journal, that I felt I’d found my niche.

I started writing there in my sophomore year. Freshman year, I had been in exploratory mode. I was taking architecture, Zen Buddhism, and anything else that piqued my fancy, without any coherence in my course schedule. Then I realized journalism would allow me to explore all these disparate interests and lean into my curiosity. From then on, writing became my focus, the narrative thread in my academic experience.

I was lucky to take narrative nonfiction classes with Anne Fadiman and Fred Strebeigh. Fred has since retired, but is still deeply engaged at Yale and has remained a generous mentor. Anne continues to teach the same course I took in 2010. Those classes confirmed for me this was what I wanted to do, if I could make it work.

After graduation, I moved to Argentina on a research fellowship. It was supposed to last a year, and my parallel ambition was to try freelancing. I started writing pieces mostly related to my research project for small outlets. One of those pieces made it in front of an editor at The Economist. They reached out and asked if I wanted to try for a job in Argentina. That worked out, allowing me to stay in Buenos Aires for four years. But The Economist is not a narrative magazine…

Right. I recently interviewed a features editor at 1843, which is part of The Economist and now focuses on narratives and longform.

1843 is such a great magazine, but it didn’t exist at the time. So working at The Economist was a diversion from my ambitions in narrative nonfiction, but it was an incredible opportunity and experience. I ended up writing narrative pieces on the side while in Argentina.

You had the narrative passion early, so you knew you were drawn to that kind of writing. Then you find this story idea, but in your mind, did you already think: Maybe one day I’ll tell the narrative story? Or were you thinking: I just want to read the narrative story somewhere?

I was thinking: I want to read the narrative story. That’s always been the type of writing I most enjoy reading. It’s just how my brain works. I was a history major, but I struggle to read very dry histories. I gravitate toward books in which history is relayed through vivid storytelling. In college, I took many classes on biography and memoir, which were very narrative-forward.

When I first learned about the Abuelas, I was 22, had just moved to Argentina, and I already aspired to write narrative nonfiction for magazines. I also suspected I’d enjoy writing a book, because I loved working on my thesis, the longest project I’d ever done. But it didn’t occur to me then that I could take on a project of this magnitude. Looking back, it’s for the best. I probably didn’t yet have the experience to do justice to the story.

That said, I’ve often kicked myself that I didn’t have the idea to write this book earlier, because its main subjects are elderly women. By the time I officially took on the project in 2021, they ranged from their late 80s to 100s. One of the Abuelas, Rosa Roisinblit, was a central subject of my book. She was incredible. Sometimes I would think: Why didn’t I have this idea when the grandmothers were younger and healthier, when I could have immersed with them more fully? But again, I was very young and probably didn’t yet have the necessary skill set.

You got access at the right time. I know you also relied on archives, but what struck me is how powerfully you wove history, characters, and science. You came in with all this historical knowledge and had to discipline yourself to make the book human and narrative. Tell me about that decision.

I never lost conviction that I wanted to ground this broader story through one family. That felt important because the events described in the book can defy belief–the state abducting pregnant women, stealing babies, and throwing its own citizens out of planes alive. It felt important to anchor that history in a structure everyone can relate to: a family. Whether close, estranged, or adopted, everyone has some form of family. Telling the story of Argentina’s dictatorship that way lets readers engage with the enormity of what happened, and connect with the complexities, how even reunions with biological families weren’t always smooth.

That said, I did struggle. In this context, where a regime disappeared people, historical memory is a powerful rejoinder. They killed people illegally, with no records of how or when, or where their remains are. The way to push back is through enshrining the disappeared in historical memory. So it felt complex to exclude people for that reason. But I firmly believed the best way to connect with readers was to stay with one family.

Yeah, I remember back when you were putting together the book proposal. You had done so much work already. Not just a little—you had practically written a huge part of the book. What was that process like? Did you already have the main characters figured out when you were doing your proposal? Or were you still working that out?

I had the privilege of working with an incredible agent, Will Lippincott. He was such an active and crucial partner, especially in the proposal phase. He asks his authors to write 100-page proposals. His philosophy is that yes, it feels risky to do that before you have a commitment from a publisher, but it gives editors such a clear sense of the book that they’ll come to you with a higher offer if they’re interested. They can see exactly what the book will look like. It’s also a bit of a filter: are you obsessed enough with this subject to produce 100 pages? If not, maybe it’s not the right project. I was lucky to have his guidance and his gentle flame at my backside.

Did that process confirm for you that: Yes, I’m obsessed, I can do this?

Yes, it definitely confirmed that this wasn’t a fleeting interest. I found working on the proposal very fulfilling, even if I had moments of panic, pouring so much into it and wondering, what if nothing comes of this?

In the proposal, I already had a pretty clear sense of who the main subjects would be. I haven’t gone back to reread it lately, but I think it was pretty faithful to how the book turned out. The general arc and even the structure were quite similar. There were diversions. For instance, I once thought about starting the book with a birth in captivity, and my editor dissuaded me. I think I even shared that scene with our writing group. But overall, the benefit of writing such a robust proposal was that I had already thought through the big questions about character and structure.

I did one reporting trip while writing the proposal, before I had a contract. Looking back, that was a very lucky decision. Argentina had completely shut down during COVID. When they reopened in November 2021, I had a four-month-old daughter, but I was desperate to make it down to Buenos Aires in person, so I decided I’d just bring her with me. I’ve since learned that traveling with babies of that age is much easier than when they get older. You strap them on your chest and they go where you go. Because not many tourists were returning right away, my flights to Argentina were like $200. I thought: I don’t have a commitment yet, but I need to go. I felt urgency because of Rosa’s age and the age of other Abuelas. I didn’t want to wait.

Yes, you have to listen to that feeling and just take the jump sometimes.

Exactly. I was privileged to be able to do so, and very lucky it worked out, because it was the only time I met Rosa in person. I was also able to download very critical court recordings that informed the arc of the book, especially the later chapters. So when I did get a contract, I already had a clear idea of where I needed to direct my reporting.

And Rosa had already shared so much publicly, her family too. That raises questions for me about trauma-informed reporting. Are you going to re-traumatize someone by walking them through something already in the record? Why make them relive it? Can you talk about how you handled that?

I met Rosa when she was 102. She told me during the conversation that it was still difficult for her to speak about the disappearance of her daughter and the theft of her grandson, but that she was happy to do so in the service of sharing the story of the Abuelas more widely. That response was echoed by the other Abuelas I interviewed, which I found deeply encouraging.

But I tried to rely on archives, court documents, and historical interviews as much as possible to avoid asking the Abuelas the same questions they had already answered hundreds of times. These materials were critical. As you know, narrative writing requires such sharp granularity. You want to ask: What were you wearing? What was the weather like? Asking a 102-year-old to recall such minute details is difficult and unfair, but I was lucky that some of those details were recorded elsewhere.

By the time I returned to Argentina, after getting the contract, Rosa had moved into a care home. Those around her said: “She’s done enough. If you want to learn more, she’s done hundreds of interviews. She has a biography.” It felt unethical to push back on that.

In the last six months of drafting, her personal archive was donated. I flew to Argentina and spent a week paging through every document: travel notes, correspondence, wedding photos, and photos with her family. Even though I didn’t spend as much time with Rosa as I wanted, I still felt close to her, and I felt I could paint an accurate and rich picture of who she was.

You did the archival work that drew this person in all the multi-dimensional narrative elements we’d want if you were interviewing them personally. So in the beginning, was that a panic point for you? Did you wonder: Am I going to get that level of detail if I can’t talk to her?

That was one of my biggest sources of anxiety while writing. There were others, but that was definitely a major one.

This book, like most historical books, really benefited from the work of other authors and researchers who had written about the dictatorship and the Abuelas before. In the author’s note, I mention Rita Arditti, who wrote the only other English-language book about the Abuelas. She sadly passed away in 2009, but her life partner, Estelle, found tapes of her interviews with the Abuelas and generously donated them to the University of Massachusetts, making them publicly available. She had done lengthy interviews with most Abuelas alive in the 1990s. Those conversations were critical and I was so grateful to Rita for her thoroughness in conducting them.

You had the challenge with Rosa, but then you had the archive to bring in. Maybe you could also talk about one of the other subjects of your book, Guillermo?

Yes. Guillermo is central to this story. That relationship was deeply sensitive, wading into family pain and trauma around adoption, reunion, and everything else. There are Cinderella stories in the Abuelas’ history, where grandchildren embraced their biological families right away, and everything proceeded peacefully. Those are real, but I felt it was important to give space to the more complex reunions, to show how the dictatorship’s brutality continues to ripple through generations.

Most recovered grandchildren, even if they struggled at first, eventually embraced their biological families and the Abuelas. I wanted to understand that transformation through someone who had lived it. I met Guillermo on my first reporting trip at the end of 2021, when I also met his grandmother, Rosa, but I had talked to him for months before that. My timing was lucky—Argentina had been locked down, so Guillermo, a busy father of three who also works with the Abuelas, suddenly had more bandwidth. We Zoomed constantly in the months before I took that first reporting trip and built a rapport. I had first contacted him through Facebook Messenger.

I’m still on Facebook for that reason. If you don’t have someone’s email, especially in another country, Facebook can be the easiest way. Guillermo was very responsive and invested early on.

He’s generous, thoughtful, and eloquent. He’s processed so much and has an incredible memory for detail. He could tell me about the sound of the ice machine at the fast-food restaurant where he worked, or the flavors of sodas there. He has a natural narrative mind. Such a gift.

The only complicated dynamic was that, as the project became real, Guillermo grew nervous about being centered over other recovered grandchildren. The Abuelas’ movement is very dedicated to collective action, and he sometimes felt uneasy being singled out. We had moments where he pulled back, and then I’d explain why it was important to center one family, and why his was such a powerful entry point.

By the end, he was excited to see the fruits of four years of conversations. He was a great sport. Before the book went to print, I sent him a fact-checking document with 350 queries. I tried to make it look less intimidating by shrinking the font and the margins, but that backfired. It just looked like a 20-page wall of text. Still, he says he ultimately appreciated the care, even if it felt overwhelming at the time.

You’d been a fact-checker before, right?

Yes, I had been a fact-checker. I was also privileged to hire one for this project–an wonderful former checker for The New Yorker, Vera Carothers, who is currently on a Fulbright in Argentina and recently published a great oral history about Argentine “artivism” in the Brooklyn Rail. Even though I know how to fact-check, it’s essential to have someone else check your work if you are able to, because if you wrote something, it’s easy to normalize it in your own mind.

In my experience, fact-checking can also interfere with writing. Toward the end of the book writing process, I was fact-checking sections myself, and the vigilance required made it hard to write. You’re constantly asking: Is this true? Is this really true? Instead of writing more freely and then checking afterward.

And you had that back-and-forth with Guillermo. When we’re doing this in-depth work, people share their whole selves, but it’s not a normal reporter–source relationship. Sometimes you almost have to explain what you’re doing as a narrative journalist. How did you have those conversations?

I talked to friends about this, and one who was extremely helpful was journalist Katie Engelhart. She said that, in her experience, sources can’t really grasp the level of investment required for long-form projects, even if you tell them at the beginning.

Right, and if you tell them up front, it might scare them away.

Exactly. It’s a balance between building trust and not overwhelming them by saying: “This will take years of your life, and I’ll need every single detail.”

And in the beginning, you don’t always know who your main subjects will be.

True. I do remember in my early conversations with Guillermo saying this was going to be a long-term project, not a parachute assignment. By the second or third conversation, I told him I wanted to center the narrative on his family, and asked if he was okay with that. I was pretty clear from the start.

And then walking Guillermo through the process as you went, over years. But his sister didn’t want to participate, right? That’s another ethically complicated situation, navigating who shares and who doesn’t. How did you deal with that?

Guillermo and his sister, Mariana, are completely estranged. They’re still locked in a court battle over reparations for their parents’ disappearance, and otherwise don’t interact. I suspected she wouldn’t want to participate. She’s also a writer and has written about her family extensively. When she declined, she directed me to her writing.

As a journalist and, as I say in the author’s note, an “incorrigible empath,” I struggled with telling such an intimate family story without all its members’ participation. I didn’t take that lightly. The way I tried to channel that empathy was by being as accurate as possible, carefully reading Mariana’s writing, citing rigorously, and relying only on the written record for her perspective. Guillermo wanted to tell his story, and Rosa had told hers many times. In the end, I felt they also deserved that opportunity, while handling Mariana’s story with care and grounding it in fact.

Yes. These are the challenges of nonfiction, and memoir too. Some family members want their stories told; others don’t. But those who do have the right to share. What matters is handling it with care, which it seems you did.

Definitely. For me, that empathy I mentioned manifests as a fierce sense of responsibility. Telling other people’s stories is a privilege. It deserves to be treated with seriousness and rigor.

And it shows, even in your opening scene. You reconstruct the kidnapping of the couple, Jose and Patricia, with such detail—the toys, the moment. How did you do that?

That scene was braided together from court records, transcripts, and one of Mariana’s blogs. It took ages to compile all the details. Fairly early on in my research, I found descriptions of José’s abduction in official government records and court documents, but there was little about the physical nature of his shop, where his abduction took place.

On a reporting trip in Buenos Aires, I visited the building where the shop was located in hopes of finding out more. But I couldn’t gain access to the interior of the building, which has since been taken over by a business school, and anyway, I had no way of confirming how much the interior had changed between 1978 and 2021 when I visited.

A breakthrough came when I began combing through Mariana’s blogs, post by post. My eyes bulged when I stumbled on one entry. It was about her father’s toy store. In it was a photo of Mariana’s grandfather visiting the toy store right before her father, José, was wrestled away from there on October 6, 1978. I could see the wood walls, the tinsel Christmas decorations. That allowed me to recreate the scene with more vividness.

Another question: some scenes in the book are brutal, violent, difficult. Yet you don’t sensationalize. The violence builds gradually and helps us understand the stakes. How did you think about handling those sections?

It definitely provoked nightmares for me. The subject matter was very hard to engage with. But without understanding the depth of brutality, you can’t fully understand the stunning courage of the Abuelas. That context was crucial.

I tried to be careful. My drafts were covered with reminders like “avoid purple writing.” I wanted those sections to be factual, not salacious or sensational. Still, they were extremely difficult to research and write.

And also being a new mother yourself, what was that like, raising kids while writing about grandmothers, parents, children?

You don’t need kids to grasp the horror of the dictatorship’s crimes, but becoming a mother during this period connected me differently to the story.

I remember going into labor and thinking about the women who gave birth in captivity. Their stories were always present in my own experience of motherhood. I started working on the story when I was pregnant with my first child, and I gave birth to my second a year after getting my book contract. I was basically pregnant with or nursing a baby for 95 percent of the research and writing process. That deepened both my connection to and commitment to telling this story.

The empathy?

Yes, and what drove the Abuelas to resist. I could understand what it means to love a child, to know you’d truly do anything for them. I was so grateful to have children while writing this book. My daughters deepened my understanding of the story, but also gifted me levity. They didn’t know I was doing hyper-dark research; at the end of a writing day, I’d see them with blueberries smeared on their faces, giggling at silly sounds, asking to go dig for worms outside. They grounded me. Without them, I might have lived only in the darkness of the material. I’m obsessive when immersed in a project, so they were an anchor to the outside world.

Technically, how did you write with two kids and a job? When were you writing?

For the first three years, I maintained a fairly normal rhythm. At first, I was freelance, fully focused on the proposal and book, which coincided with having my first daughter. I took my academic job at Yale when I was deep in the research phase, but the juggle still felt manageable. Then it got very intense. The last year or so became pretty grueling as I tried to finish.

Like you, I wrote during early mornings before the kids woke, evenings after bedtime, and lots of weekends. For about nine months to a year, I worked more weekends than not. There weren’t enough hours in the week otherwise.

The hardest moments were in the long stretch when I couldn’t see the end and really missed spending time with my kids, particularly on weekends. I was writing and writing and writing, but I couldn’t gauge where I was in the process. Once I saw the finish in sight, things became easier. It was still hard, but I’d always wanted to write a book, and this story in particular. I didn’t want to waste the opportunity to finally do it. The intrinsic motivation and the recognition that the more intense rhythm would not last forever made the grind possible.

Did the new semester start at Yale? Can you tell us about the program?

Yale classes started recently. The Yale Journalism Initiative has existed for 20 years. Its mission has always been to help Yale students who want to become journalists. The program serves as a bridge between all of Yale’s incredible writing instruction and the professional world of journalism, which is more opaque than other professions like law or medicine.

What does that mean practically? I meet with a lot of students one-on-one to listen to their ambitions and try to provide guidance. I hear from everyone, from first-years without a single byline who are curious about campus journalism to seniors with experience at major outlets looking for jobs. We also bring inspiring journalists to campus to show the many different paths into journalism. And we have funding to support unpaid and underpaid internships.

One last question: what writers inspired you while putting your book together?

Oh, so many. Certainly, Patrick Radden Keefe’s Say Nothing was a huge model. My copy of that book is marked up and dog-eared to the point it’s hardly legible anymore. Bob Kolker’s Hidden Valley Road. Books by Hampton Sides, who is masterful at weaving historical narratives. Isabel Wilkerson. Rebecca Skloot’s The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, especially for balancing science with accessibility. And also Erik Larson.

Steve Coll, too. I worked as his fact checker. That experience ignited my desire to write this kind of book, and I returned to his work often.

*Note from Erika: After Haley and I had this conversation, Rosa Roisinblit, the main subject of the book, died on September 6, at the age of 106. Haley offered a few additional thoughts about Rosa, whom readers get to know so intimately in the “A Flower Traveled In My Blood.”

I am grateful to have played a part in preserving her story of courage and resilience for future generations. Rosa’s remarkable longevity accurately reflects the force of her determination; she remained an active member of the Abuelas until her 102nd birthday, fighting to find the grandchildren of her fellow Abuelas long after she had found her own. She was a fierce advocate for truth, however painful its telling might be. “I have always told my story exactly as it is,” she told me when we met. “The truth, before everything.”

I pretty much devour everything you write, Erika. And thank you for the mention.

What a beautiful interview with Haley! I remember that afternoon at our writers' group when she shared her proposal and we were all riveted. I'm so happy to see her book in the world.

And thanks for the shout-out for my Substack!