Writing With ‘Interiority’ in Narrative Nonfiction

Abigail Leonard on getting inside her subjects’ heads

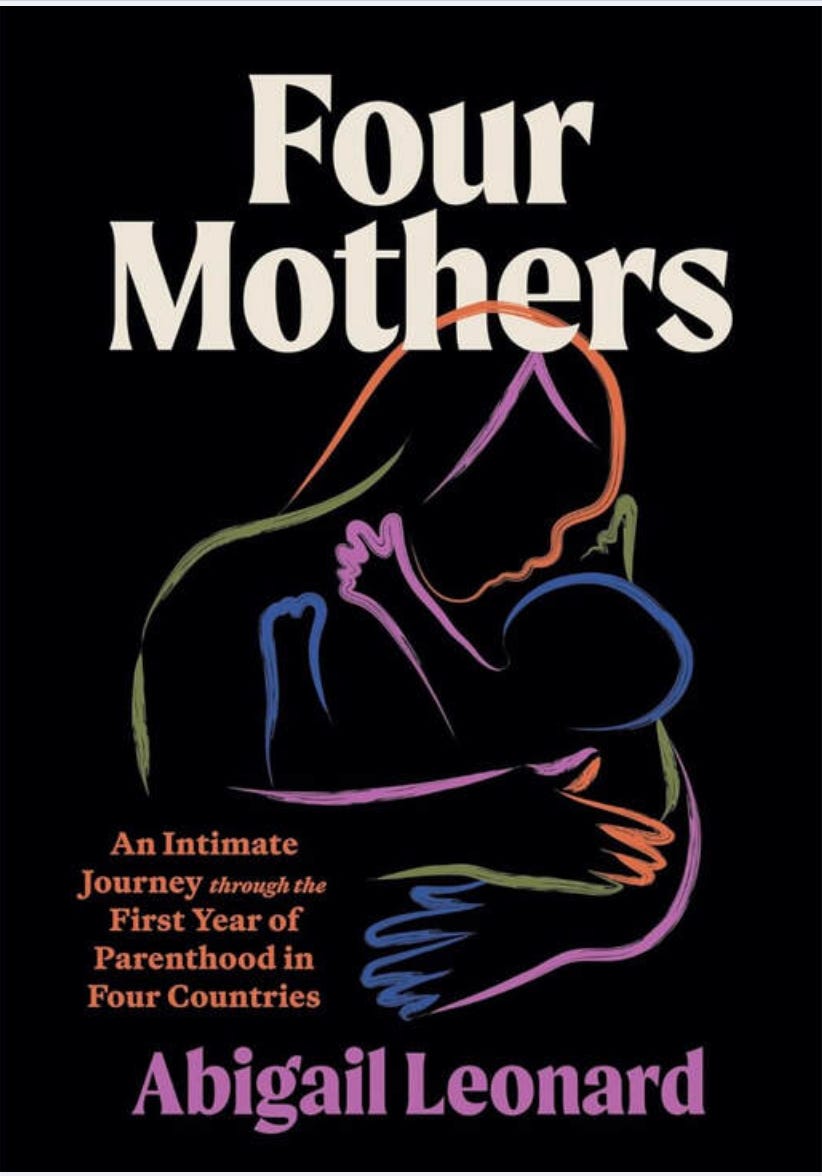

Last year, I received a galley of journalist Abigail Leonard’s book, Four Mothers, which follows the journeys of women in Japan, Finland, Kenya, and the U.S., as each navigates their first year of motherhood. In her introduction, Abigail describes her reporting endeavors as a new mother herself who had moved to Japan and started asking questions about how different societies support families. She quotes the poet Muriel Rukeyser: “What would happen if one woman told the truth about her life? The world would split open.”

The New York Times offered a glimpse of that truth this week, speaking to women across the country about the real cost of motherhood in the U.S., for a video short that I first watched on TikTok. Four Mothers, which was released last month (and has already been named as an Amazon Best Nonfiction Book of 2025), goes even deeper into the daily realities, using specific techniques of narrative nonfiction to report intimately on her subjects.

Abigail begins in the style of a reported essay, positioning herself as the narrator and guide into the worlds of new mothers. Her book feels in conversation with Essential Labor or Like a Mother, both by Angela Garbes, or more recently Second Life: Having a Child in the Digital Age, by Amanda Hess—books grounded in journalism and reflection, weaving facts, scenes, and research with personal observations.

But as I delved into Four Mothers, I was particularly struck by the close attention Abigail devoted to each woman she profiled. After the intro, she shifted away from her own point of view, and instead wrote relying heavily on her subjects’ interiority. Here is Abigail describing the emotions, thoughts and feelings of Tsukasa, as she goes through childbirth in Japan:

She’s sweating, though she’s not sure if she’s hot or cold. Waves of contractions seize her like a vise around the midsection and she struggles to remember what the nurse had said about how to stay calm. There is the emptiness where her husband should be—where he would have knelt to comfort her.

Free Indirect Discourse

In traditional literature, this approach of writing a scene in third person through the sensory experiences of a character allows a reader to feel closer inside the protagonist’s perspective. It collapses the narrative distance between reader and character, and feels more immersive. This technique relies on free indirect discourse, as the narrator shifts seamlessly into the character's perspective, tapping into human-condition inquiries.

When nonfiction writers delve into the minds and feelings of the people they write about using free indirect discourse, it seems as close to fiction as the reported form can get. The reader is experiencing the scene—in third person—through the emotional lens of the real-life individual going through the events on the page. Journalists love to zoom out. And we must, to convey the social dimensions and implications beyond a single person’s story. But zooming in is a tool for powerful narrative.

Tom Wolfe once described his approach to interiority and the “new journalism” this way:

“Sometimes I used point-of-view in the Jamesian sense in which fiction writers understand it, entering directly into the mind of a character, experiencing the world through his central nervous system throughout a given scene.”

In reported stories, I prefer writing close-up and viscerally, when it is possible (I once got away with a lede about motherhood and creativity almost through the view of a rat). When I notice journalists taking a free indirect approach, I often find the writing highly readable. But readability should not be mistaken for being easy to report. Every detail still must have a source.

Reporting for Interiority

You may obtain some of this interiority through records—email, social media and texting trails, court transcripts, journals, letters, videos. Meanwhile, to achieve such a felt-life literary technique through human interviews, a writer must peel the layers of a scene, asking specific sensory questions: What went through your mind? Can you walk me through that moment again? What did you see? Can you describe it? Did you say anything? If so, what? What song was playing? Whose voice did you hear in your mind? What did the air smell like? What did you regret? What did you fear? What happened next?

Interviewing for these emotions and memories can be quite hard to do and even uncomfortable, because it involves psychological questioning, building relationships and trust with sources, relying on memories, and fact-checking for accuracy. It may also involve going back over a particular scene multiple times with your interviewee to see if you as a journalist interpreted their feelings correctly, and “triangulating” with other reporting, as Abigail put it.

Here is how Kim Cross detailed her process of fact-checking with subjects to me last year:

“Errors of nuance are one of the dangers of narrative. You’re using your vocabulary as a writer to convey the emotional experience of someone who's not a writer, who doesn't have the same vocabulary. So you lean on your words, but your words may or may not accurately convey what they’re trying to say. So I feel like it is my responsibility to go back and say: ‘This is how I described your experience. Do my words feel true to you?’”

It is helpful to break down the steps of points of view, and how journalists move between each one as a narrator: Inside the mind of a subject. Or on someone’s shoulder. Or across the room. Or hovering high above the scene. Here is a Google Doc with throwback examples of ledes and lines I sometimes share with students showing this closest narrative stance.

More recently, Sarah Topol’s story, “The Deserter,” in The New York Times Magazine leans on interiority, as does Rhana Natour’s “Coming to America,” in The Atavist, both of which won national magazine awards this year. (*The Atavist, by the way, is looking for pitches of “deeply researched and carefully crafted” longform nonfiction stories, according to Study Hall. Rate starts at $6,000 for 8,000 to 30,000 words.)

It was a pleasure speaking to Abigail for this Q&A. Abigail discussed how she crafted a narrative proposal that sold, and how she approached reporting like a documentary producer when tackling a book to achieve such immersive reporting from afar (she does not live close to any of her subjects).

Abigail is an international reporter and news producer, previously based in Tokyo, where she was a frequent contributor to NPR, Time, and The New York Times video. She has also worked as a staff producer for PBS, ABC and Al Jazeera. Her work has earned a National Headliner Award, an Award for Excellence in Health Care Journalism, an Overseas Press Club Award, and a James Beard Media Award Nomination.

Our interview has been edited for length and clarity.

I know you come from a broadcast background, but what’s your trajectory into journalism? And how did you get to the point where you decided to write a narrative book?

I have a master's degree in journalism. I went to NYU and did the Science, Health, and Environmental Reporting Program. In undergrad, I studied anthropology. It may have helped my reporting, thinking about anthropological studies of different societies.

I always liked to write. I interned at Newsday and at CNN. At Newsday, everyone was telling me that the newspaper jobs were on the decline, and everyone was being laid off. It was a terrible time to get into newspaper journalism. But CNN was growing. I liked broadcast journalism too. So part of it was a practical decision.

I ended up working for the medical unit at CNN. Then I worked for PBS for a while and did more longform news documentaries, which I loved. That was incredible. So that was, I guess, the broadcast version of a book—because it's long, you get to build character, you get to set scenes, travel to places, and really get to know a place and understand a story. And PBS is a place that cares about reporting on policy. So I got to do all of that, and I learned from some incredible people—mentors who are still mentors to me—and just really learned the craft of journalism in a way that I don’t think I even learned in my master’s program.

Some of the work is very tedious, like going through transcripts and doing really intensive fact-checking, and then trying to build a narrative from that. Trying to find a through line in a person’s life, which isn’t always clear at the beginning, because people move in different directions. So I learned a lot there.

Then I actually worked for a couple years doing political analysis shows, which was totally different. I worked for Keith Olbermann and Jennifer Granholm, who went on to be the Secretary of Energy. They had daily news shows. My PBS show had gone away, so I had to find something else. I had to write like 15 minutes of television each day. It was completely different but really fun. It wasn’t like building stories over months, it was literally hours. I got really good at writing fast.

You need to learn that sometimes.

I actually enjoyed it. It was a different kind of voice, and writing what comes out of an anchor’s mouth is different than crafting a story.

I went back to more documentary work at Al Jazeera America. Then my husband got a job that brought him to Japan. I was pregnant and moved to Tokyo when I was six months pregnant with my first child, which was sort of crazy in retrospect.

My plan was to work from there, but it was challenging with the whole dislocation of moving to a new country and new motherhood. Later on, I was also able to do some work. I had two more kids in Japan and ended up reporting for NPR, because I’d always wanted to get into radio. I also did some print work, like for The Washington Post.

So with narrative writing, it sounds like you really picked that up just because you got to work with longform, documentary-type work? Do you feel like the narrative muscles translate across the genres, from documentary to book-writing?

I do think some of the skills I learned in broadcast writing helped me. In broadcast, you often string out your sound first. You gather your sound bites, and then think about the B-roll you're going to lay over it to set the scenes. I approached the book in a similar way.

I never took a formal class in narrative writing, not even in undergrad, so my approach was shaped by broadcast. I’d figure out what I wanted the characters to say, what the strongest quotes were (which is like sound bites in writing), and then I’d build scenes around them. I’d talk to the subjects about the scenes, then flesh them out more when I was on the ground, looking for details.

When you do broadcast filming, you're always searching for strong visuals. I had that mindset when writing. I was always looking for evocative scenes, sights, sounds, smells. All the sensory detail you can include in a book but not in broadcast.

I also worked with local reporters to find the women and help me report over the year, because I couldn’t be in every place at once. That’s also a broadcast structure: you have field producers who gather material and work closely with senior producers to get exactly what’s needed. I’d often write all the questions, and even if I wasn’t doing the interviewing myself, I’d make sure we captured the scene properly. It was kind of like having a shot list or a question list, very much like a producer would do.

Yes because producers don’t always travel for every story or every scene. How did the idea for a book take shape?

It was after we came back from Japan. My youngest was not even a year old, so I was still in that early stage of motherhood, again, for the third time.

The concept for the book really stemmed from my own experience, understanding the difference between Japanese and American approaches to supporting mothers. In Japan, there’s a strong support system, but also deeply entrenched gender roles. In the U.S., there’s more professional opportunity, but far less support. I wanted to explore that contrast somehow.

At first, I thought maybe it would be a magazine article or a radio piece. But in the dream version, it was always a book. So I just kept working on it. Eventually, I wrote a nonfiction proposal, got an agent, and that was the moment I thought: Okay, maybe this really can happen.

But before that, I was hesitant to say it out loud. To others, I’d just say, “I’m working on a project,” because I wasn’t sure where it was going.

I know that feeling. You don’t want to jinx it.

Exactly. I didn’t want to get ahead of myself. The whole thing, even in retrospect, feels kind of amazing. All four of the women stuck with it, their stories came together, things I couldn’t have predicted made them more interesting. It really worked out. But it was a leap of faith.

Did you find all your subjects before writing the proposal?

Yeah, I was pretty deep into reporting before I wrote the proposal. I wanted to include as much as possible, since I’d never written a book before. I needed to prove I could do it and that there was enough material.

Also, on a personal level, we moved to Japan for my husband’s job, and I just felt this strong need to have something of my own. I think that need helped propel me forward. I’m not sure I would’ve stuck with it in the same way otherwise. I just had this deep drive to create something big that was mine.

Did you leave your job for that move?

Yeah. I left my job at Al Jazeera, which was a great job. I was reporting from the West Coast for a national news magazine show. That never happens. Usually, everything is East Coast–centric. It was a really good position. But I gave it up.

I get that. I also have family in Japan. My dad was born in Osaka, and I’ve got a lot of aunts and cousins there. Some of them are mothers now, and yes, the gender roles are really baked into society still.

Totally. I came from San Francisco, probably the least like that in the U.S., and then just got thrown into a totally different cultural reality.

You feel it immediately. So, do you have any advice for someone working on their first book proposal? Sounds like you did a lot of upfront reporting and had your characters figured out. The proposal process is such a mystery to so many people. You even landed your agent with the proposal?

Yeah, I really overprepared. I don’t know if I overwrote it, but I did a lot of work. I had a strong sense of the narrative arc, tons of background research, and enough to show I could handle it all. I think doing more only helps. So I did a lot.

Yeah, same here. I’ve done reporting for proposals that didn’t sell. It happens. It’s really hard these days.

Yeah, and I got a lot of rejections. People said things like: “Moms don’t read books,” or other dismissive stuff.

But women and moms do read books.

Exactly. But I guess they need something to say when they reject you. I just kept going until someone said yes. It definitely didn’t happen right away.

That’s how it works. Just keep submitting. By the way, I remember reading Lisa Taddeo’s Three Women. I imagine people compare your book to that one. Was that in your mind while shaping your structure?

Yeah, definitely. When I was writing the proposal, the book wasn’t called Four Mothers yet. It had another title, so it wasn’t overtly tied to Three Women. But yes, I thought a lot about structure. At first, I even considered doing it like Three Women, with just the women’s stories and no outside reported context. But I’m glad I ended up including the political and social parts, it added a lot. There were a few other books I studied too. One was Strangers to Ourselves, by Rachel Aviv. Also Adrian Nicole LeBlanc’s Random Family, and Katherine Boo’s Behind the Beautiful Forevers. Those aren’t all structured the same way, but they do follow characters. And I was thinking about how to do it, and I didn’t know if I should just have each character in their own section, or weave them together, like in Three Women, which is effective, because then you can compare them to each other.

I also had the chronological structure of one year, so then breaking it up into three chunks—like pre-birth, first six months, second six months—made sense. And I put in the different themes, like maternal health care, paid leave, and then childcare. In broadcast, there’s so much structure, you're always creating these storyboards. So I tried to be as structured as possible.

The structure is easy to follow. You get what’s happening immediately, and you’re moving through time with each person simultaneously.

It’s so obvious now, it makes sense. But at the time, I really struggled. And then even to figure out which story to put first. I decided to put the U.S. at the end to land there, so it’s all an implicit comparison with the U.S..

How did you find everybody? Especially because you’re working in other countries.

Well, in the U.S., I actually posted on mothers’ sites, or mom groups, to ask if anyone would be willing to participate in the project. And then I had more choices. I really liked Sarah. I thought she was open. And obviously you want someone who's open, and funny, and just talks and talks.

Also, she’s a teacher. Her husband’s an Amazon delivery driver. She felt very American. She left the church, which also feels American. And she was a first-time mom.

To find the other ones, I did work with local reporters, or fixers. They were amazing. In Kenya, the woman I worked with was so wonderful and smart, and she found Chelsea and really helped me connect with her throughout the year, because that was the hardest story to report on from afar. We worked closely together, and she was able to follow Chelsea. She would take videos and take pictures and do lots of interviews, and I would talk to Chelsea directly, and then she would talk to her.

Tsukasa in Japan didn’t even speak English. So similarly there was a woman I worked with there, a fixer, who is one of those people who could pull things out of her hat. I had to do something about COVID in Hokkaido, and she found me a million sources in a weekend.

How did you find the fixers? Did you go through a fixer network?

I knew the fixer in Japan from living in Japan, and she was really active in the journalism community. To find the other ones, I looked online. There were some postings, and on LinkedIn. The fixer in Kenya did a lot of work for The Washington Post.

And then there was one other Kenyan fixer I used who was a recommendation of a friend at The New York Times. They had all embedded, and were clearly very good at their jobs.

In Finland, a fixer helped me find Anna, but then after that I just communicated with Anna directly. And Anna sent me a lot of photos of her own. And Tsukasa did too. Basically after she gave birth, she sent me an entire rundown of what had happened. Time-stamped: and then they gave me oxygen to help me breathe. Then the doctor came in, and then I felt like this.

I could ask her in the next interview about it. She was even taking pictures of the food she got while she was in the hospital afterwards. She was very into documenting this. Which was like a sort of a collaboration, too. They understood what I was trying to do.

It’s helpful now that people can document their own journey, and how those records can be used in a written project that feels different than social media alone.

Yes, I feel like there is a lot of technology in this book. It was super helpful to have all those kinds of technology. Videos, texts. I could just be in constant touch with them. Without that it wouldn't have been possible.

You were able to draw a lot from all of the women, particularly in felt-life scenes and details.

With Chelsea, I would realize that I had a question about the transcript, and I could just text her and she would get back to me. All of them were really good about it.

And then when I was there in person, they would have told me something in a phone interview and I would go visit the place where they told me something had happened, or they would take me there. I remember Chelsea took me to the place she got her daughter’s ears pierced, and she was like, "Oh, it’s the same chemist." So I could describe the woman who was also in the pictures I had and the videos I had. So it was all triangulating.

That makes sense. One thing I really admired about the book is that you had that interior life of the people. A lot of journalism stays at a distance, or it hovers high above. But to get close—to get to how someone feels in the moment of childbirth, or right after, or even in flashbacks—you need to have those deeper conversations. That takes a certain kind of work. Can you talk about your process of writing through people’s points of view, instead of from above, like the journalist surveying everything at once?

Yeah, I thought a lot about that. One thing I was mindful of was that if I wrote too much from my point of view, I’m American, so I come to this with all kinds of preconceived notions. I wanted my presence to be light. I didn’t want to get in the way.

And yes, I definitely wanted to get inside their heads. I was trying to be as factual and accurate as possible, but all I had to go on was what they told me. So I’d ask them the same questions again and again. How they felt in that moment. And I’d try to talk to them as soon as possible after something happened, so it was still fresh.

Getting their authentic feelings was key. That was always a focus in interviews. Trying to access their interior lives. They would recall conversations, and I’d try to represent those accurately. So I used a stylistic device: if it wasn’t a direct quote—if it was a recalled or reconstructed scene—I’d put it in italics to signal to the reader that I wasn’t there. It’s such a balance, trying to be accurate, trying to be in narrative, and trying to get into people’s emotional truths. It’s hard.

Yeah, it’s really hard. It reads so easily, but writing it? Totally different.

And figuring out what’s less interesting or less useful, that’s hard, too. I had so much material, and I had to cut a lot of it. That’s always a challenge.

You do weave in these brief moments of social context—why this matters. Earlier, you mentioned being glad you did that. You referenced Three Women, and how that book focused entirely on interiority without explaining a big broader social lens. But you made a conscious choice to include that context. Otherwise, we may just be inside people’s lives with no clear sense of why. Your reporting is conscious to not just be voyeurism. Can you talk about that process?

Yeah, structurally it’s helpful to provide context. There’s so much to explain. Why people are doing certain things, how they’re giving birth, for instance. That context matters.

But really, I wanted to convey a bigger message about the intersection of politics and motherhood. Motherhood is inherently political. It’s shaped by social structures we don’t control, like where we happen to give birth. That place determines so much about daily life.

So I wanted to bring history and politics into each story to help readers understand the pressures these women were under. And the more I learned about history, the more I realized how much I didn’t know. How close we came to things like universal daycare, paid leave, and how those efforts were blocked. It was enraging.

Looking at other countries and why their systems are different helped me see that it’s not just, “Oh, this is 2025 and this is how America is.” Why don’t we have the support systems others do? So I was glad I included all of that. It helped me understand, and it felt a little relieving. Like, this isn’t all my fault. We carry so much personal responsibility, but we’re also operating within massive systems.

And when I talk about the book, mothers really respond to that part. I was worried at first. Is it too much policy? But it turns out women are hungry for that kind of information.

Right. How did we end up here? We tend to internalize everything, like it’s all our fault, when in fact it’s structural. There’s a reason we’re at this point. So I think it makes sense that women respond to that. But was it hard to include that without overwhelming the narrative?

Definitely. I worked hard to keep it narrative. To weave it in rather than drop big chunks of policy. And there was stuff I found fascinating, but it was just too much. You can’t include everything about, say, colonialism. But I tried to focus on what mattered most to the story.

I also wanted to show how things change over generations, and can change again in the future. That felt hopeful. I had to go back in order to go forward, in a way.

How many drafts did you go through? I know you had a lot in the proposal already.

The proposal had the first part—the first four chapters, one per woman—but I went back and re-did it with new research and new things they’d said in later interviews. I don’t even know how many drafts. So many. It was fluid, constantly revising the same sections. I’d work on a chunk, like the Kenya section, dump everything in, and slowly chip away.

You blocked it out like we do with childbirth. We forget the pain and then do it again.

Totally.

Once the book was out in the world, and since you had these close relationships with the women in it, how did you handle their reactions? There are even photos of them in the book. How did you prepare them for such personal stories being made public?

I wish I had prepared them more. They were fine in the end, but it caused me a lot of stress. I talked to a lot of journalists about how to handle it, how much to show them in advance. I went back and forth about giving them the full draft, which you're not supposed to do. But I didn’t want them to be surprised.

So I did intensive fact-checking with them. I’d say, “You said this. Is that right?” I didn’t let them read the full thing, but I sent them early copies of the book. They couldn’t change anything at that point, but they saw it before the world did. And then I just waited anxiously.

That’s the most stressful part.

I’ve definitely had people get very upset before. It’s hard. But I keep reminding myself: my job isn’t to make people happy. It’s to be accurate and fair. I’m not their friend. They entered into this relationship knowingly, and I’ll do what I can to protect them, but we’re not writing hagiographies. We’re trying to tell a larger truth.

If you didn’t get anything wrong, that’s all you can do. Some people will be upset, and others, surprisingly, won’t.

Be accurate and fair. And giving people the chance to prepare, like you did. Without letting them edit the whole thing. It’s agonizing, but it’s part of writing about real lives. That intimacy makes the book powerful. The distance we see in some books—where we don’t really get to know the people—avoids that, but at the cost of depth. And your book has depth.

Yeah, it’s so stressful. I was like, maybe next time I’ll just write fiction. No people to deal with!

I know some people only write about dead people. Too stressful otherwise. And now that it’s out, do you feel like it’s a birth in a way? Your first book, done while being a mother?

Yeah, it’s a lot. It’s scary. I was in an author chat group with other first-time authors, and it reminded me of being in a birth group. Everyone’s due around the same time, and then they start having their babies and reporting back, like, “It’s wild.” And I was like, Oh God, I’m not ready. But then my day came. And now I’m in it.

And unlike birth, people actually tell you what they think of your baby. Which is terrifying. You put your soul into this thing, and people can criticize it, or worse, ignore it. Getting attention is its own challenge. You think, "If people read it, they'll like it." But first you have to get them to read it.

We don’t think about that part when we’re writing. That we’ll have to be our own publicist. You have to keep pitching, like journalists pitching stories. It’s ongoing.

Yeah, you really have to love your subject, because you’re going to be talking about it a lot.