Janet Malcolm Told Him: 'You Betrayed Journalism'

Sheon Han on writing as an ‘attentive form of existence'

I taught my last class of the academic quarter last week (summer does not officially start on my campus until mid-June, and even later for those of us still grading). Hoping to send students off on a high note—despite everything feeling so upsetting right now—I invited journalist Sheon Han to Zoom in and talk about having a writing life. Sheon published his first freelance piece in 2021, and since then his writing has appeared in The New Yorker, WIRED, The Atlantic, The New York Times Magazine, and many more.

It wasn’t until our discussion with Sheon ended that I realized how much some students needed to hear his advice. Truly talented young writers have watched other classmates find jobs, get into grad schools, receive awards, or land freelance assignments with major publications. Meanwhile, their job and internship applications have been met with rejections or silence. Some have found themselves rooting for their friends—while also comparing themselves, wondering: Am I even good enough?

Even those of us who are veterans recognize this kind of envy and self-doubt. I love how Pulitzer Prize winner Jennifer Senior offers such an honest note about envy in her 2022 reported essay, “It’s Your Friends Who Break Your Heart.” She includes a scene about her close friend Bob Kolker and his book, Hidden Valley Road, being selected by Oprah. Senior writes of “the cramped quarters of my ego, crudely bound together with bubble gum and Popsicle sticks.” Was his achievement as amazing as she told him? “No, it wasn’t. I wanted, briefly, to die.”

Sheon’s visit, several students told me after class, helped remind them of why they want to write. Professional envy can bring on feelings of insecurity. But it can also fuel writers to identify and sharpen their ideas of what they want. Sheon’s drive and passion for magazine storytelling resonated. He is a writer based in Palo Alto, California, and today he is sharing some guidance he gave to the class with you—along with answering a few bonus questions for The Reported Essay.

A Podcast Episode

I will be posting more good stuff in this newsletter throughout the summer. In the meantime, I wanted to drop this link to a podcast interview I did recently for the Institute for Independent Journalists and its Freelance Journalism Podcast, also available on Apple Podcasts. It’s with Isabelle Kohn, a senior editor for Slate, who specializes in stories about sex, gender, relationships, and work. Happy to report that one of my students pitched Kohn after this interview—and landed an assignment.

I first connected to Isabelle and Sheon through this very newsletter. So thank you to both of them—and to all of you—for continuing to support my work and The Reported Essay.

I hope you enjoy this insightful Q&A with Sheon.

You are a relatively new freelancer, how did you first discover magazine and feature writing?

As a Korean citizen, I had to serve in the Korean army for two years. And they blocked access to most websites—news, social media, and whatnot. But one of the few websites I could access using my military computer was this website called The Electric Typewriter. It was like a precious corner of the internet that wasn’t blocked. They have an archive of the 150 best pieces on art or classic journalism, like stories by Hunter S. Thompson or Joan Didion.

I printed out a bunch of these pieces — probably unauthorized use of my work computer. I would read those magazine pieces while pretending to do work. I think I read a lot of them during my downtime or work hours. But back then, I don’t think I even knew those were magazine articles. I just thought they were good writing.

But then I remember the first time I became aware of a magazine as a magazine. My then-girlfriend, now my wife, Yeseul, sent me a Rachel Aviv profile of the philosopher Martha Nussbaum in 2016. That piece was incredible. I was a philosophy major then, and I thought, I’m sure I’ve read New Yorker pieces before, but this—this is what magazines can do.

After that, I just started reading things religiously, listening to the Longform podcast, reading long reads from every source.

That’s so interesting. You kind of stumbled into it just from reading great articles and narrative pieces, and then you decided you wanted to try to do this?

Yeah. So that was during my military service, which I did in between my freshman year and sophomore year in college — I left for two years and came back because I wanted to get it over with early, and most of my friends would still be there as seniors. I don’t know if people know this but if you’re an international student with a non-STEM degree, you only get 12 months of work authorization after graduation, until you get into the H-1B work visa lottery, which has an increasingly low selection rate. But if you have a STEM degree, you get 36 months, which means you can apply for the annual visa lottery three times. So I changed my major from philosophy to computer science, which had been my minor. It was a huge blow to my ego. That was during a time when everyone was majoring in computer science, not to throw shade, but, you know, I thought I was a philosopher but now on paper, I was a tech bro.

In the end, it wasn't a terrible bargain because it made me comfortable with technical concepts, and I am still in this country as a green card holder. But in my senior year. I was struggling with this image of myself as a literary person versus my actual major. Then one day I was talking to a freshman, and he randomly mentioned this journalism course that was being taught that semester. It was called “The Art of Profile.” Princeton has this program where visiting professors come for a semester, teach one course, and then leave. This one was taught by Rebecca Mead.

This single course changed my life. The class was already full, and I thought it wasn’t going to work. But Yeseul said I should still send an email. And luckily Rebecca just ignored the class quota and let me in.

That’s when I really realized I wanted to do this. For 12 weeks, each class featured a New Yorker staff writer who came in and talked about a profile they had written. One week it was Michael Schulman on Meryl Streep, then Raffi Khatchadourian on Julian Assange, Jia Tolentino on Gloria Allred, which was her first profile for the magazine.

Then there were guests like Larissa MacFarquhar, Rachel Aviv, Andrew Marantz, Nick Paumgarten, and, finally, Janet Malcolm. I was taking four courses that semester, three of them being computer science because I had credits to make up for. But I was spending 80 percent of my time on that journalism course.

You realized you loved it?

It was the only thing I wanted to do.

So it was just one class. How did you turn that into an experience where you could actually get published? How did you start learning how to be in this journalism world, coming from a totally different background?

In my last semester of college, I took one more journalism course taught by Jim Dwyer, a longtime columnist at The New York Times. He was incredibly generous. One of those people with gracious, old-school virtues. I remember a Times reporter who was a guest speaker telling us that Jim would always be the first to approach new reporters at company parties and make them feel at home.

For two years after graduating college, I didn’t reach out much to Jim or Rebecca because I wanted to have something good to show them. Something that would make them proud. I didn’t want to just ask for help.

I graduated in 2018, and I don’t think I was very diligent about pitching or continuing to write post-college. I sent out a few pitches but they didn’t get accepted, and I was busy with my day job. Then, in 2020, with the pandemic and remote work, I suddenly had time to write in the morning because I didn’t have to commute.

In June 2020, when George Floyd was murdered, I wasn’t sure it was safe for me, as a non-citizen, to attend protests. So I emailed Jim to ask about the risks. He gave me practical advice about what to expect, and at the end of the email, he added: “By the way, Sheon, I just learned I have early-stage lung cancer. I’m having surgery tomorrow. So far, there’s no sign of it spreading, so I’m optimistic. I should be back by the end of summer.”

We kept exchanging emails. A month later, he told me the surgery had gone well, which was a relief. But then, a couple of months later, I opened the New York Times website and saw his obituary.

That moment really hit me. I had waited two years, and now it was too late to show him what I could do with what I'd learned from him. I was devastated. Reading the comments in his obituary and what people posted at the time of his death, I was profoundly moved by how many lives had been touched—and often saved—by this great-souled person. I admired his infinite generosity but he had passed away so early, in his early 60s. I spent weeks in sorrow, rereading his old pieces.

I realized I couldn’t keep waiting. That’s when I really started pitching, because I didn’t want something like that to happen again. A couple of months later, I got my first piece accepted.

It sounds like, for you, the loss of a mentor was also a turning point? Like, it was now or never? Every writer goes through times when nothing is working out. What helped you keep going?

I hope this doesn’t sound a little too romanticizing, but for me, writing is the one thing that brings me this intense, quiet focus. Especially in the morning when it’s early enough to be completely dark. There’s a kind of blissful concentration I can only get from writing. I think living as a writer is one of the best forms of life I can imagine.

I’m a curious person. In college, I always audited extra classes because I wanted to learn more. But I didn’t think I could become an academic who needs to be an expert in only a few areas. I remember Tom Bissell once said writing a book is like getting a master’s degree. For me, working on a feature story feels like taking a semester-long course. Two features? That’s a double-credit course. A book? Maybe a PhD. It’s the most immersive way of living I know.

That comparison to taking a class or getting a degree through writing articles or books—I hadn’t heard it put quite that way before. It really resonates.

You know this already, but the journalism industry is so opaque, especially freelance pitching. I didn’t know what pitching was at all. I was scraping together advice from random articles on the web and listening to tons of Longform podcast episodes. Probably half their archive.

The archive is all still available.

Yeah. One thing that helped was a freelance writer community Study Hall. They had pitch databases and stuff. But beyond that, it really came down to pitching well, not necessarily pitching a lot.

I usually spend a long time writing pitches. I think it's important to use your pitch as a chance to show that you can write, give a sense of your voice and style in the pitch itself.

Show that you can write a feature in the pitch itself, not just describe the idea. Did you study other pitches or get feedback on yours? How did you navigate that?

Not really. Most of my journalist friends were staff writers, so they didn’t really understand the freelance pitching world. I wasted months doing things I shouldn’t have, like sending pitches to generic submission addresses. That’s my number one rule now: Never send to a generic inbox. Always find an individual editor.

When friends ask me about freelance journalism now, I have a little packet—which I am happy to share with anyone who reaches out. I send them with rules like that and sample pitches. I didn’t have a mentor, and I hesitated to ask for help. But I don’t want other people to waste time like I did.

What was the first piece you landed?

Actually, two got accepted around the same time. One was in Catapult—an essay about my long-distance relationship and how that’s kind of the default for immigrants. The other was a book review in The New Republic of an anthology of philosophical science fiction. I think The New Republic piece came out first.

Student question: How did you maintain a relationship with an editor after the first pitch and story?

It’s usually pretty natural. If you enjoy working together, and the editor does too, they’ll often email you asking for more ideas. That’s been the case with me and Wired. After a while, you get a sense of whether you enjoy working with that editor or publication. There’s no formal follow-up. It just evolves.

Student question: This might sound obvious, but a few of us are pitching completed pieces. Have you done that? How does it compare to pitching just an idea?

Yeah, my very first pitch was a completed draft of a profile from a class. It didn’t get accepted, but perhaps there was enough substance to get actual rejection emails, which was better than silence.

If you have a completed draft, you can choose whether or not to mention it. Most editors don’t like it, some don’t mind. Writing on spec is risky, because if they don’t accept it, you’ve spent a lot of time for nothing. But editors also do a lot of shaping and sometimes even restructuring the whole piece. I’ve written on spec only once. It’s better to pitch the idea and adjust based on what you discuss with your editor.

That first pitch I ever sent was actually to The New Yorker. Probably impossible to get accepted, but I figured, why not? I pitched a profile, and sent it to an editor named Anthony Lydgate. He didn’t accept it, but years later, he ended up being one of my editors at Wired. So even when a pitch gets rejected, you might work with them again later.

Exactly. Relationships carry over between publications. Editors remember you, and when they move, they might want to bring in writers they already know. Every pitch can open a door, even if it’s a rejection.

Student question: Do you write from a particular lens, maybe influenced by your computer science background? Or do your stories span a range of topics, and you pick the publication based on the topic?

That’s a great question. When I first started, I wanted to pitch to every culture section at every magazine. But I realized quickly that each magazine, and even each editor, wants something different. Even within the same section.

So now, if I have a story, I think really hard about where it fits. For example, I once thought about pitching an essay about a Korean term called gwichaneum, which doesn’t quite exist in English. It means something like “lazy,” but more nuanced. It was a culture essay, but there were only a few places whose culture sections would be a good fit for it. I published the piece, “The Case for Selective Slackerism,” in The Atlantic. So now, I think not just about the publication, but the specific editor.

Yeah, you also have a mix. You do first person, book reviews, science pieces, more narrative magazine work. You wrote a reported essay for The New Yorker on “Steven Yeun’s Perfect Accent in ‘Minari,’” which weaves in some of your own personal reflections. Can you walk us through one of your favorite stories?

Many writers I admire are versatile. They do criticism, profiles, and reporting, and those forms inform each other. That mix works for me. Usually, pitching takes a lot of time. If I need to pre-report, I have to talk to people; if I’m reviewing a book, I need to read the author’s past work. But the pitch for the Steven Yeun piece came to me somewhat organically. During the pandemic, I was at home watching “Minari” with my wife and my brother, and in the middle of the movie, as I was listening to Steven Yeun speak, I had one of those rare, sudden self-realizations—when a half-formed thought I hadn't been able to articulate for a long time coalesces into a clear picture.

I remember scribbling in a small legal pad as I was watching, and I knew what I wanted to say. The piece was pegged to Oscar season, so I had fewer days than I would've liked to write the draft, but it came together without much friction, perhaps because I was drawing from something so personal, already etched into my bone and marrow, which I was just bringing to the surface.

What is another favorite piece you worked on?

“A Tale of Two Clubs” is, in a way, the first longform piece I ever published. Nassau Weekly is a student-run magazine at Princeton, co-founded by David Remnick in 1979 when he was an undergrad. The piece is a critique and a kind of "quit lit" essay about an eating club called Ivy, which I used to be a member of and eventually left.

There's a raw, rough-edged energy to the piece—I was a college senior, after all—but it's meaningful to me because it was my first time feeling that electric sense of being read. After the piece was published, it became the second most-read article in the magazine's history, according to the web editor. I received texts from friends who had already graduated and emails from alums.

But more than that, it was the first time I felt I had managed to fully project my interiority—to make visible what I think and who I am as a person—and how writing can humanize the writer, who might otherwise remain a nameless and inscrutable presence.

Looking back now, it's wild that I had the space to just write and publish a 5,000-word essay. So perhaps a practical tip for students is to take advantage of school publications, because the freedom to write long features every week if you want to doesn’t come so easily later on.

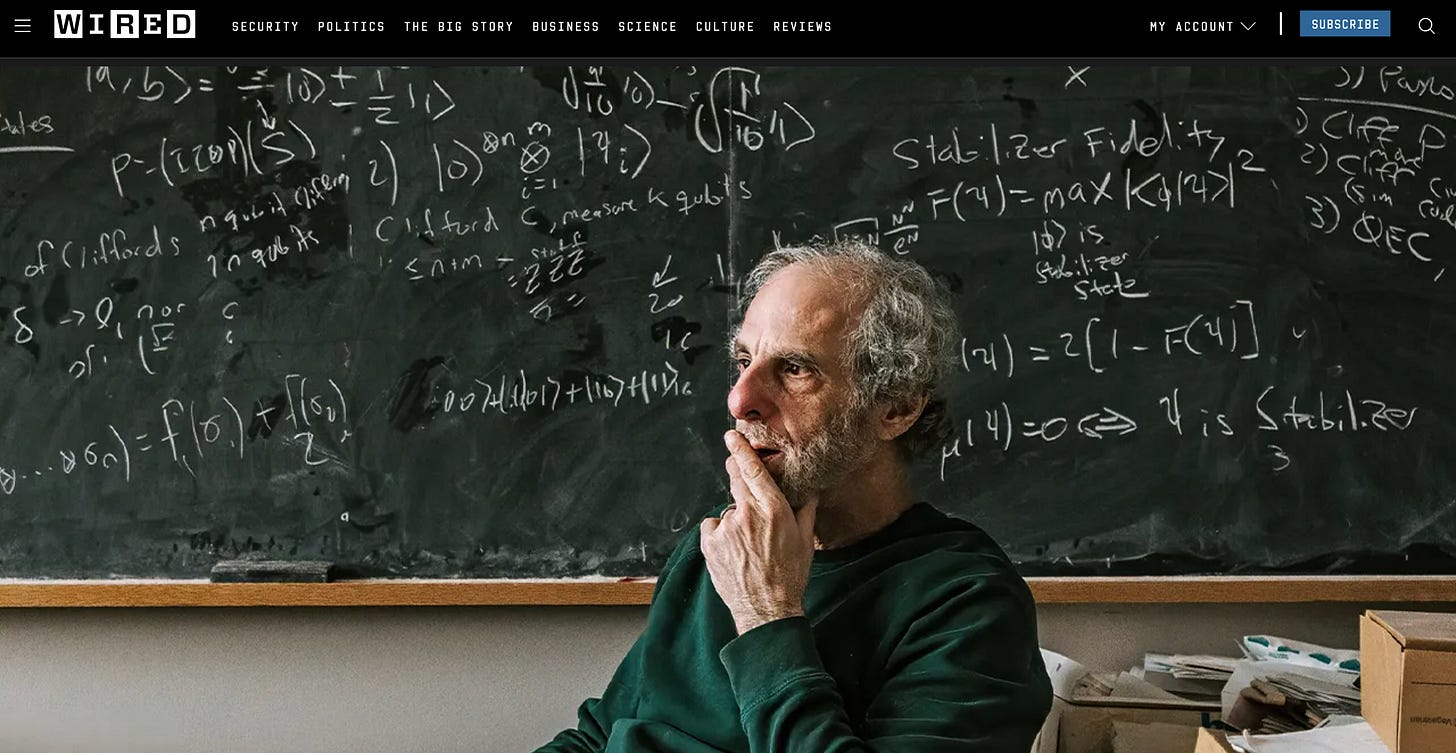

You also recently published a Wired feature about an online repository and its creator, “Inside arXiv—the Most Transformative Platform in All of Science,” which is really a profile.

This piece was about one of the arguably most consequential platforms in modern science. I initially approached it as a kind of profile of an intellectual institution, part of which would also become a profile of its creator, Paul Ginsparg.

But as I kept reporting, it turned out to be much more about Ginsparg as a complex person—I admire him a great deal for his honesty and integrity. He’s the type to call out that the emperor has no clothes. He can be blunt, but never in a hostile manner—rather in a strangely inviting way that made me feel as though I’d been granted the equal license to be direct during the time I spent time with him.

Still, as I spoke with people who had worked with him, and even old friends, many admitted that he could be difficult at times. To be clear, not abusive, but intense and unrelenting in a way that some found hard to handle. I don’t think that kind of tenacity should be uniformly villainized; in fact, in this case, I came to believe it’s part of what helped this embattled institution survive.

There was a stretch when I found writing this piece difficult because it brought up that age-old question in journalism. It’s painful to realize that something I’ve written might be seen by the subject as unflattering—but I also know it needs to be there for the piece to be more than just an anodyne, feel-good profile. I never want to write a hit piece, but writing a hagiography is also bad journalism.

It’s an oversimplification, but I think there are two poles when approaching that question: Janet Malcolm and George Saunders. Both arrive at truth, but the emotional valence of their work is diametrically opposed. Malcolm is one of my lodestars—someone I always come back to reread, but her pieces are often not without a trace of meanness, even malice, some would say. In both his fiction and journalism, Saunders has a way of being generous without lapsing into schmaltz. But in less skilled hands, following his approach can risk veering into sentimentality.

Which other writers do you admire?

When I first started reading magazines, Larissa MacFarquhar’s work left an indelible imprint on my understanding of what great journalism can be—for example, through her profiles of Harold Bloom, Aaron Swartz, Hilary Mantel, Derek Parfit, and others. Her book Strangers Drowning, about extreme altruists, is one of the most sublime books I’ve read.

What’s more, her work is profoundly revealing, yet it doesn’t commit psychological or moral violence against her subjects. That’s such a difficult balance to strike but she maintains this almost mystical equilibrium.

I once met Janet Malcolm when she came to the class on profiles taught by Rebecca, as the final guest speaker. During the Q&A, I mentioned that I’d profiled a philosopher who had said a few things that, if included, would have cast him in a bad light—so I left them out.

She looked at me, smiled, and said: "You betrayed journalism." There was a moment of dead silence, and then the class burst out laughing. She said it in a way that was unmistakably teasing—not intimidating at all, but playful. Still, that moment stuck with me. And for the longest time, I wasn’t sure if I really had betrayed journalism.

A couple of years ago, I got to know Larissa, and I asked her about her thoughts on Malcolm's famous pronouncement in The Journalist and the Murderer. What she told me was incredibly thoughtful—I'd risk butchering it if I tried to summarize it—but the upshot is that it simply freed me from that dilemma. Even before our conversation, I had believed that one does not need to betray one's subjects to do good work—because Larissa had been doing exactly that—but her response confirmed it, and it was reassuring to hear that from the very person.

A student question: You mentioned editors you enjoy working with. What attributes make an editor a good fit and foster a strong working relationship?

Responsiveness is always nice. Also, when you feel your editor truly values you. I’ve worked with two Wired editors—Angela Chen and Jason Kehe—who made me feel this way. They’re thoughtful, supportive, and trust me. Jason and I even drank two bottles of wine on our first meeting—and yes, as a Korean, I appreciate the kind of bond sealed over alcohol. He shared my thoughts about how tech journalism could use more imagination and invention, and he gave me freedom to pursue stories. That made me feel really valued.

Finding those editors is crucial. How did you cultivate these relationships?

Pitching to various venues helped. I got to work with a number of editors. Over time, I learned to trust when I felt valued and recognized. You also need to negotiate edits. Trust your editor’s instincts, but don’t adopt suggestions blindly. When they point out where something needs to be fixed, they're invariably right—but how they think it should be fixed might not be. And when you do come up with a better way, they will trust you more.

Is the life of a freelancer having a mix, rather than focusing on one type of storytelling or job?

I’m still figuring it out, but I do love all of it. My spiritual background is in literature and philosophy, and reading literary criticism shaped me. I was actually afraid of reporting until my editor assigned me a piece about a concept called “migratory grief,” which involved talking to people from Ukraine, Hong Kong, Afghanistan. But overall it was relatively light reporting, so it wasn’t intimidating, hence a gentle introduction. A big perk of freelancing is if you have a day job to pay the bills, you never have to take on a piece you don’t want. I’ve never been forced to do something I was not invested in.

Great advice. What do you do as a day job, and how do you balance freelancing?

So, I code. But I have complicated feelings—almost a moral guilt—about being in tech. Because I had a computer science degree, I could only work as a programmer. Until I got my green card in 2022, I could not get paid for any of the writing that I did. If you’re on an H-1B visa, it's illegal to work in something that's not tied to your degree.

When I was moving from New York to the West Coast, I wanted to get a job that might be useful experience as a writer even when my role would be programming. I thought, Huh, what's a company that writers are obsessed with? Twitter. I also had this weird boundary, because I did not want to work for Uber or Facebook, but then I thought Twitter was different. Like we all complain about Twitter, but many Twitter users hate Twitter the way New Yorkers say they hate New York--they don’t. It was a moral compromise that I could make. I joined Twitter the week Jeff Dorsey resigned. Five months later, Elon Musk decides to buy this company. I completely overlapped with the whole saga. Elon Musk takes over, he fires half of the company, half of my team, I did end up writing about it.

I left three weeks after Musk's takeover, and freelanced full-time for about 18 months. It wasn’t miserable, but it was hard. Living in the Bay Area on freelance income is tough. Plus, writing to pay the bills can make you resent the craft. You only have a few good writing hours a day. Maybe three or four. When I had a day job, I’d write early before my first work meeting. As a freelancer, I wasted those hours. I learned that having a day job that doesn’t drain you, so you can write in the mornings, is valuable.

Perhaps structure matters more than passion. Even a job that lets you clock in and out can leave space for those precious writing hours.

Exactly. I thought I could maintain structure without a day job, but I couldn’t. I struggled to wake up as early, and that was disheartening.

Yes, we often dissect pieces we love and figure out how to apply those techniques in our own work: how to pitch, how to structure, how to start. Can you also tell us about your book? How did you get into writing the proposal?

It started last December. I had been working on a different book and shared the proposal with my agent, but I eventually decided it wasn’t the right project for me at the moment, so I paused it.

Then, around that time, Elon Musk had a feud with MAGA over the H-1B visa on Twitter. I remember seeing "H-1B" trending, and it struck me because my life was so tied up in that visa. If I hadn’t gotten it, I would’ve been kicked out of the country.

Around the same time, a green card holder was detained, and student visas were being canceled. I’ve read a lot about undocumented immigrants, but I realized I knew little about other legal immigrants. We may not be undocumented immigrants but we are certainly over-documented immigrants.

Now I’m a permanent resident, more bureaucratically, a "permanent resident alien." There are a lot of interesting stories around legal immigration, and I wanted to tell those. The working title is Resident Aliens. We’re not naturalized citizens or second-generation immigrants. We’re in between.

So it’s a mix of personal essay, reporting, and history with different chapters focusing on various visas and types of immigration status: like when the first Korean student graduated from a university in the U.S. in 1891; how H-1B was created; why the fastest way to get U.S. citizenship is to serve in the military; what kind of people get visas for "aliens of extraordinary ability." And along the way, answer a question for myself: should I naturalize—a strange word, by the way—and if so, how do I do it with integrity, since I'd have to give up my Korean citizenship?

So it’s narratives of different individuals, braided with your reporting and personal stories?

Exactly.

Do you have any final thoughts or advice on the writing and freelancing life, as many students graduate and embark upon their own journeys?

On writing, I personally find it vital to have a "first reader" you can trust—someone who reads your drafts with care and insight before anyone. My wife has been that first reader and editor for every single piece I've written. Having been married for years—and known each other since high school—means she doesn't need to hold back, and I can take brutal honesty without being offended.

Whenever she points out something in a draft and I ignore it, my editor inevitably flags the exact same issue. She is a historian and has an unerring sense for what works and what doesn't. Maybe I'll write about it someday, but for now I'll just add that I insist on paying her a share of any fee I receive—because, needless to say, unpaid labor from a spouse is still unpaid labor. We don't do this for anything else—just for writing.

On freelancing, this might sound banal, but don’t give up when you face rejections starting out—being passed on and pitching again is the name of the game. Living as a writer, even if it’s not your full-time job, can be such an attentive form of existence.

Thank you for this amazing conversation. And yes, “Strangers drowning” is a beautiful book and it also helped me to better understand my work and values 🩵.

This is such a generous piece. Thank you Sheon for your insights and Erika for your questions!