‘Why are we the people asking questions others avoid?’

Adrian Nicole LeBlanc on journalists and ‘The Vulnerable Subject’

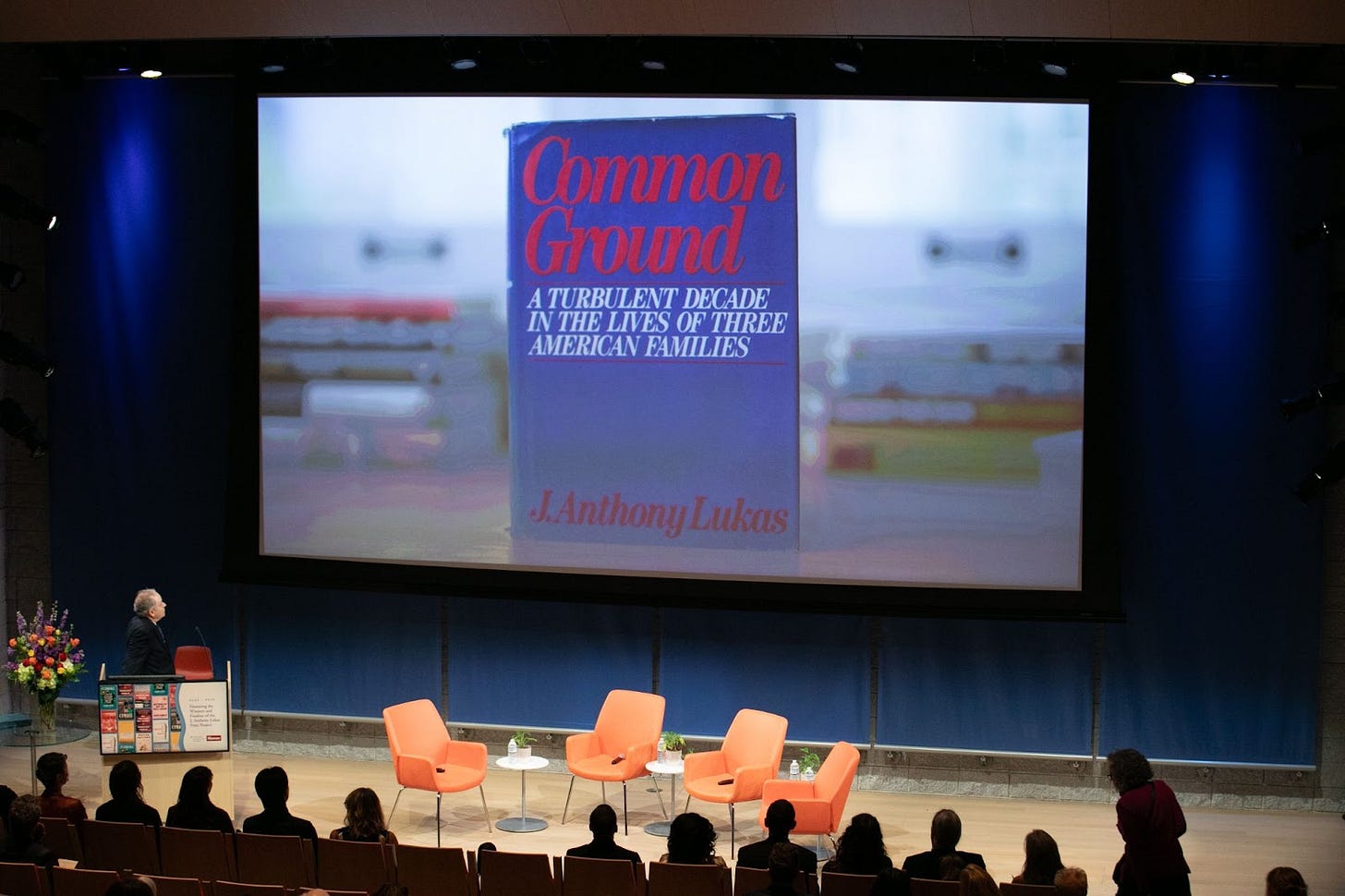

In 1985, the Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist J. Anthony Lukas, whose work examined critical fault lines in America’s social and political landscape through the lives of individuals, gave a remarkable quote to interviewer Diane Osen for the National Book Foundation, who asked why he found writing about families so compelling:

“All writers, I think, are, to one extent or another, damaged people. Writing is our way of repairing ourselves. In my own case, I was filling a hole in my life which opened at the age of eight, when my mother killed herself, throwing our family into utter disarray. My father quickly developed tuberculosis -- psychosomatically triggered, the doctors thought -- forcing him to seek treatment in an Arizona sanitarium. We sold our house and my brother and I were shipped off to boarding school. Effectively, from the age of eight, I had no family, and certainly no community. That's one reason the book worked: I wasn't just writing a book about busing. I was filling a hole in myself.”

Lukas was discussing his seminal book on race, integration, and the busing crisis in Boston, “Common Ground: A Turbulent Decade in the Lives of Three American Families.” But his quote is surprisingly introspective, coming from a journalist. Often we tell ourselves—and everyone else—that it was a subject, a question, the news, or a social concern that pulled us to pursue a particular story. Rarely do we get into the psychology behind our journalistic impulses, or the larger forces shaping our ideas and approaches to reporting.

Lukas committed suicide in 1997, before his final book was published. “He wasn’t so much looking for truth in its purest sense, or the quaint satisfaction of solutions,” writes LynNell Hancock in the Columbia Journalism Review, “as for something much bigger, much messier.”

In May, a roster of brilliant honorees gathered for the ceremony of the J. Anthony Lukas Prizes, created in the author’s memory. Their narrative nonfiction books, on topics of American political or social concern, exemplify his commitment to research and social responsibility. You can watch the ceremony and Q&As with awardees on YouTube or on C-SPAN.

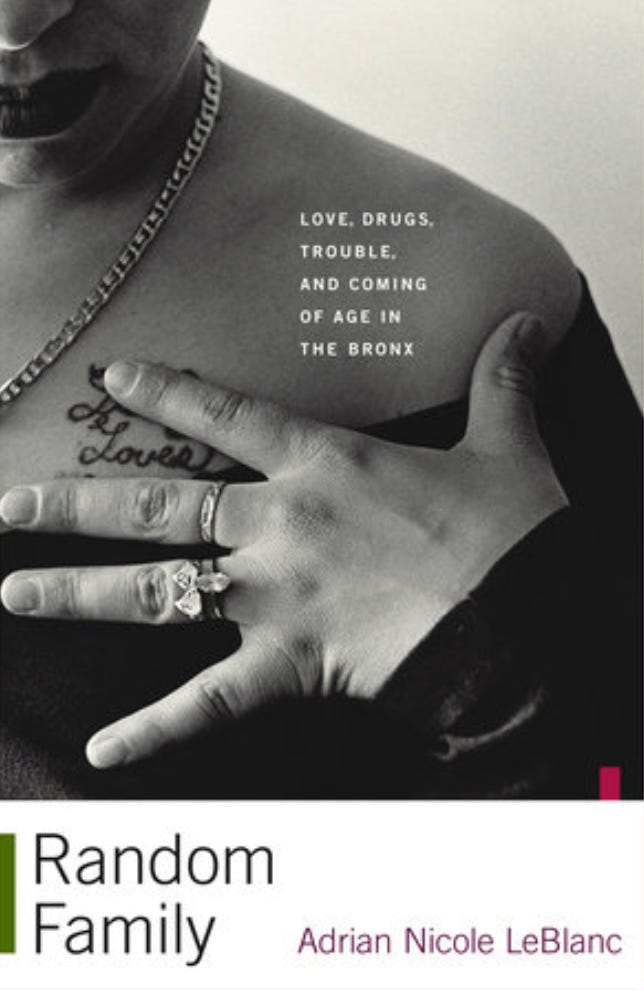

At the Lukas ceremony, I had a brief chat about the subconscious motivations of journalists with another legendary narrative nonfiction writer, Adrian Nicole Leblanc, author of “Random Family: Love, Drugs, Trouble and Coming of Age in the Bronx.” LeBlanc’s book is a widely studied and enduring work of literary journalism, “unflinching” in its attention to details and intimate moments in the lives of the young people she followed.

A continuation of my conversation with LeBlanc is the focus of today’s Q&A.

The New York Times named “Random Family” one of “The 100 Best Books of the 21st Century.” In 2013, The New Yorker wrote: “LeBlanc’s subjects sold drugs, did drugs, committed murder, went to prison, had sex, fell in love, got pregnant, fed their children. They shared ambitions and fears with a writer who was by their side for a decade.”

I learned that LeBlanc has taught a class called The Vulnerable Subject, which explores some of the same questions Lukas articulated when he talked about “filling a hole.” Her class also engages in the kind of conversations I think about often in my work and teaching, issues like positionality, power dynamics, and trauma-informed reporting.

LeBlanc has inspired generations of narrative journalists. In the short time I have been publishing this Substack, writers including Abigail Leonard, Lauren Smiley and others have mentioned LeBlanc’s reporting as being profoundly influential on their own. “Random Family,” Smiley told me, is “just the bible on non-exotifying people that are involved in a crime.”

Like Smiley, I first read “Random Family” two decades ago. At the time, I was a young reporter at the Los Angeles Times covering the education beat, and I found it to be a pivotal work of nonfiction, expanding my ideas of narrative journalism. It was also one of the first books I taught as a professor. I assigned it to my undergraduates again just last quarter. LeBlanc’s reporting and writing still deeply resonates, leading to passionate discussions about class, crime, poverty, craft, ethics, and immersion journalism.

Our Q&A delves into LeBlanc’s approach to teaching students about the vulnerability of the subject and also the writer, as well as how it has evolved over the years. If you want to learn more about LeBlanc’s craft and reporting in particular, I will point you to essential resources I started with when I first began to study her work:

—Robert Boynton’s interview with LeBlanc in “The New New Journalism” remains one of the very best out there for writers—delving into questions about how she discovered the story, how she organizes ideas, what obsesses her, how she approaches interviews.

—“Telling True Stories: A Nonfiction Writers' Guide from the Nieman Foundation at Harvard University,” features essays by many notable narrative journalists, including one by LeBlanc: “(Narrative) J School for People Who Never Went.”

—“Literary Journalism: A New Collection of the Best American Nonfiction,” reprinted LeBlanc’s must-read piece, “Trina and Trina,” originally published in a different form in The Village Voice.

—In 2013, The New Yorker interviewed LeBlanc for “‘Random Family,’ Ten Years On.”

—And I also appreciate this short video clip with Katherine Boo and LeBlanc, recorded in 2014 at the New York Public Library.

I hope you enjoy this discussion with LeBlanc, which has been edited for length and clarity.

I’m interested in the class you’re teaching—or have taught. What exactly is the class about?

The class is called “The Vulnerable Subject.” I haven’t had time to research where in the history of journalism the academic conversation around vulnerability or empathy really begins. There are all these ways it’s been talked about. It’s my sense that the default assumption tends to be about conjuring empathy in the reader, or for the people in the story.

The class explores these issues along with a related one, which often gets subsumed by the discussions of objectivity and subjectivity, and the powers at play. All crucial, but the class is trying to get the writer or reporter to understand that it’s their connection to their own humanity that is the primary lens through which they’re viewing whatever world they are in--that they are vulnerable as well. It’s one shared world, the one in which we live.

There's this habit of going into places where “story” gets defined almost exclusively by the harms or problems done to them, by social inequalities. How does the writer accurately render vulnerability to those forces when capitalist hierarchies are ideologically organized by personalizing vulnerability and casting blame?

The framing can make ordinary human behavior seem exceptional or surprising while normalizing catastrophic oppression; this requires real consideration of this complexity narratively. What may present as a challenge of characterization, for instance, may be solved by further contextualization, or exposition on the dynamics operating in that context.

But even in other situations, perspective can skew unintentionally when the writer isn’t aware of how their own biases are operating in the piece, which aren’t only biases of their own, but those in the assumptions of the culture at large--about what constitutes “story” to begin with, for instance. Not to mention the vast gaps in knowledge--of history, for starters, or an industry a person is working in. And of course the writer exists within the framing, however it is drawn.

I think writers need to be alert to the fact that their needs, traumas, stigmas, biases—all of it is playing out in the work. And you have to be cautious about being too sure of yourself in understanding what’s resonating and why.

There’s a term in social sciences, “positionality,” laying out where a researcher comes from, their biases, traumas, life experiences—all the factors that shape their identity and work. Is that something you’re thinking about too from a journalistic standpoint—acknowledging where we come from as we pursue stories?

That’s a really good question. I do think one of the differences—though of course the modern writing business has changed a lot—is that in the social sciences, there is an established process. You're trained, evaluated, and shaped within your academic field. You learn to use cases that came before you. There’s shared parameters and rigor.

I’ve not been to journalism school, but my students often have to move fast and make meaning with limited time and knowledge. Our reportorial processes are sometimes improvisational. In the past, people might have developed deep expertise on a beat over time. But now, there’s pressure to create something out of a very brief observation or experience. That’s one issue.

Also making a statement about your position and your experiences, that's great, but that's still limited to our own understanding of ourselves at a given point in time. Healthy journalism means its practitioners are always learning and growing.

You mention writers being alert to how their needs, traumas, stigmas, biases play out in the work. Do you have any thoughts on how we can tune into that ourselves—or how you have done so in your own work?

I have learned a lot from reading widely about scientists and artists, about how other professions “listen,” so to speak. I found psychologist and ethicist Carol Gilligan’s “The Listening Guide” to be an especially helpful method for some more recent projects. The tools she has developed encourage us to see research relationally rather than as some solo information-seeking quest.

I can’t begin to do justice to it here, but her method’s tools can be adapted to some reporting. They can help one “hear” one’s initial ideas, motivations and interests, and also help to prepare to actively listen in ways that bolster curiosity over quick binary meaning-making.

That being said, the usefulness of the tools depends upon the practitioner and the parameters of the story and all sorts of other things. There’s tremendous variation in the needs and skill sets, which is why creative nonfiction can be such an exciting genre.

Journalism is changing. And I remember you mentioning this idea about why we as journalists are drawn to certain topics. Are you also asking students to think more about that?

Yes. Though I know that’s a privileged question. Many writers don’t get to choose. They take what pays. But I do think about it a lot.

I don't know if it's a romantic notion of a journalist, but in the old days, when you had local newspapers and you had local reporters, you're writing about a community that you live in, usually, and you're held accountable. You're walking around the streets, and if people have an opinion about what you're doing, they're going to tell you or you’ll get feedback in some way. You're not filing a story about some place you don't have any grounded and ongoing connection to.

There are advantages and disadvantages, of course, and all kinds of arrangements and stories, but being regularly present in a community or place forces a more ordinary accountability, and even if it’s not possible, the questions it provokes are helpful to consider: Would you write the same story if you knew you'd see these people in your neighborhood for the next five years? If your children play on the same softball team? It’s similar to early discussions about community policing: there's a big difference between being a police officer in the community you live in and driving two hours to another town to do your job.

What feels familiar, say, or dangerous? Why does it feel that way? How does it shape what one chooses to use in the writing, and what proportion might those details take? Do the feelings change the actual focus of the text? I think those questions are often underneath some of the questions I’ve been asked about what people call “intimacy.”

There’s also a discipline to this work that proximity at a certain part of the process can sometimes compromise. So much solitude is required! We’ve chosen a profession that requires us to find ways into places that aren’t our own. Or into familiar worlds we want to understand better. Why are we the people asking questions others avoid? Why are we asking: What’s going on here? How do you feel about it?

That idea of intimacy comes up so much in narrative journalism—when you're inside someone’s world, or in their head. That closeness is often what makes something memorable. But we’re still outsiders.

Exactly, and yet I am not sure I believe it to be entirely so. I remember in LynNell Hancock’s piece about J. Anthony Lukas in the Columbia Journalism Review, she noted that she couldn’t tell who his favorite characters were, that he gave everyone a fair shake. That’s remarkable. But I also believe you can write a piece where love is obvious, and still be clear-eyed. We do love people, imperfectly. And that doesn’t necessarily always disqualify our judgment. It might make it sharper sometimes.

I often think when we're reading literary journalism, we may read it like a novel, but we can't just analyze it like a novel—because there are human experiences we can’t even see happening in the background.

Yes, including that of the writer to one’s audience. You're trying to write in a way that if a practitioner of the form is reading, they understand what you're doing, right? But if a layperson is reading it—you're trying to have them enjoy the engagement with the story without stepping out of the narrative. That's a problem, if you step out and explain what you're doing in the actual narrative, it can break the experience of the scene. Although so much contemporary creative nonfiction is finding elegant and exciting ways to better address accountability.

Facts place demands on the possibilities of narrative. I remember there was a draft of “Random Family” where I had all these scenes in prison, and my editor said: “You can only have one or two visits to prison in the entire book.” That's it. And I can't even tell you how many times I went and reported in prisons. But the editor said: “You can use everything you learn from all of those visits. You just can't show it with each scene.”

So there’s a scene in the book that describes going into a prison and what you go through to enter. That's where all those scenes I witnessed got broken down and put into this kind of index of experiences. It's sort of like a roundup of all the details that you learn, but you're not locating them to a specific prison, a specific time, with a specific character, even though some of that is how you got that information.

So when you teach, how do you guide students to think about these questions about vulnerable subjects in their own work?

I encourage them to practice self-awareness. To periodically take an inventory, and to try and unearth their blind spots. For example, when playing back an interview, notice when you may have missed a follow-up question. Ask: Why didn’t I ask that? Were you shy? Intimidated? Distracted?

And I tell them to develop a “cabinet” to guide them: teachers, books, peers. To try and make at least one good writerly friend during your program, someone who challenges your assumptions and reads your work with care. But, also, be as good a reader of their work as you want them to be of yours. And that's a real commitment. It’s hard, editing someone else's writing. It is very time-consuming.

Ideally, this person will stick with you through your career, and as you grow into new problems in your writing, you’ll have developed a shared language. It can add to the joy of tackling whatever you next need to address. They might say things like: “You’re over-explaining again,” or “You’re avoiding X or Y here!”

We all need people who’ll tell us the truth. We may need advice as we navigate complex situations. Best not to be alone in those decisions and it takes time to develop trust. You're going to write some good stuff, and some mediocre stuff. And you've got to keep learning. And—this is advice I wouldn’t have taken when I was younger—but it’s really important to take care of your health and to pace yourself.

Yes. No one warned me in journalism school that I could absorb other people’s trauma. So when you talk about mental health, is that something you’ve processed yourself?

Yes, and now there’s more awareness in the profession. Journalism schools and news organizations have trauma-informed training and other support. It’s important for your own well-being, and for protecting the people you write about.

You want to be a good guest in people’s lives and, ideally, in the house of the story. Doesn’t matter whose house it is, whether it’s a Wall Street office or someone’s personal life, you have to be aligned with your values and your purpose. That’s a high bar, but aiming for it helps.