The Story 'Hook'

What happened when I tried to write about Chinese and Black history in Mississippi

In 2021, during the Covid lockdowns, I sat in on a few virtual classes at the University of California, Irvine (where I also teach journalism), including one by Claire Jean Kim, a professor of political science. It was a period of Black Lives Matter protests and anti-Asian violence, and at the time Kim was finishing her book, Asian Americans in an Anti-Black World, which was published in 2023.

In her lectures, Kim shared a brief lesson on Black and Chinese American history in Mississippi—about a time when Chinese immigrants had moved to the south to work on plantations. Kim mentioned a point that stuck with me: By the early 1900s, about 30 percent of Chinese men in Mississippi were married to or living with Black women. Many of these couples had children, some of whom had been later rejected by their Chinese family members. I am mixed, raising mixed kids, and I was curious to know what happened to the descendants of the interracial couples and their children from Mississippi.

So I began searching for living relatives connected to one couple I found in history books: Emma Clay, a Black woman born on a Mississippi plantation in 1865, and Wong On, an immigrant from the Canton Province, who worked on the Transcontinental Railroad before moving to Mississippi. The couple married in 1881. I started tracking names on Ancestry.com, searching for phone numbers and addresses attached to those names on the people finder, Intelius.

I received a reporting grant from the wonderful Knight-Wallace Foundation, which allowed me to travel to the Mississippi Delta and elsewhere to interview these descendants in person, some of whom did not even know of each other. I came back with rich interviews and a wealth of research.

But I realized, while trying to pitch and publish the piece, just how difficult it can be to get editors to commit to a story about a small segment of society that dates back to the late 1800s and early 1900s. For a long time, I failed to secure a home for the story. I felt guilty. Some people I interviewed died before knowing if the story about their family would run.

I put the piece aside for a while—until recently, when filmmaker Ryan Coogler released his hit vampire movie “Sinners,” to great fanfare. “Sinners” takes place in the Mississippi Delta in 1932, and it happens to include Black and Chinese characters who have close relationships. This storyline (inspired by documentary filmmaker

) raised the question for many viewers unfamiliar with this history: How did the Chinese end up in Mississippi?The film’s release gave my story a fresh “hook” (so thanks, Coogler). Admittedly, my original reporting started out quite ambitious in scope. I had envisioned an epic longform narrative. I ended up publishing a solid news feature. Sometimes as freelancers we just have to put an idea on pause, keep thinking, or wait for the right moment to try again. Sometimes, we also have to let go of what we cannot completely control.

I am grateful to the editors at Smithsonian Magazine for accepting my pitch, after I figured out the “Sinners” hook, and editing it so quickly. Thank you also to my friend Maya Kapoor, for first spotting this potential hook after listening to this Fresh Air interview with Coogler.

Here is the recently published piece.

Perhaps one day I will do more with the research on Mississippi and the descendants I met that did not make it into this version. In the meantime, I am adding a few photos and extras from my reporting at the end of this post.

Why Now?

I am teaching a class on historical narratives, and students have read work by Isabel Wilkerson, Michael Luo, Wright Thompson’s The Barn (also set in the Mississippi Delta) and others. Recently, students submitted story pitches drawing from historical events. I also referred them to examples in the Open Notebook Pitch Database.

In my Mississippi pitch, I had to work on the same note I gave to many of my students—answering ‘“why now?” Most magazine feature pitches need a nut graf explaining why this story matters in this very moment, and why people should care about it now. That answer might come from conversations in the zeitgeist, events in the news, scientific breakthroughs, social topics in conversation.

For history stories, it may be harder but not impossible. My class also read this 2019 piece, by Adam Hochschild, about a period in the early 1900s: “When America Tried to Deport its Radicals,” which feels particularly salient today.

I want to echo advice that Hochschild offered when he recently visited my class, which he says he is happy to also share with you. The co-founder and former editor at Mother Jones magazine is also a celebrated author of 11 nonfiction books, many about historical events, as well as scores of magazine articles. He admitted, even his ideas are often rejected.

Hochschild told students:

“There are all kinds of reasons why magazines turn down ideas, and it doesn't necessarily mean that it's a bad idea. It just doesn’t fit what the magazine is looking for that month, or that week, or whatever. So get used to being rejected. Always have a list of a half a dozen places in which you’re going to try to pitch your story idea. The moment you get turned down by the first, try, the second.”

A Reporting Fellowship

For anyone out there looking for programs that might help fund the stories that you feel compelled to report on, I recently came across this post for a Reporter in Residence for the Omidyar Network. It is aimed at helping “freelancers make ends meet while engaging in deep, nuanced reporting that drives national conversations, but may not always pay the bills.”

Applications are due soon, May 30th. Candidates who advance to the final round of interviews but are not selected for the residency will receive a $2,500 stipend. The Summer 2025 program runs from July to December of 2025. Each reporter contracted will receive a stipend of $8,000 a month and $2,000 travel budget (totaling $50,000).

The Best American Series

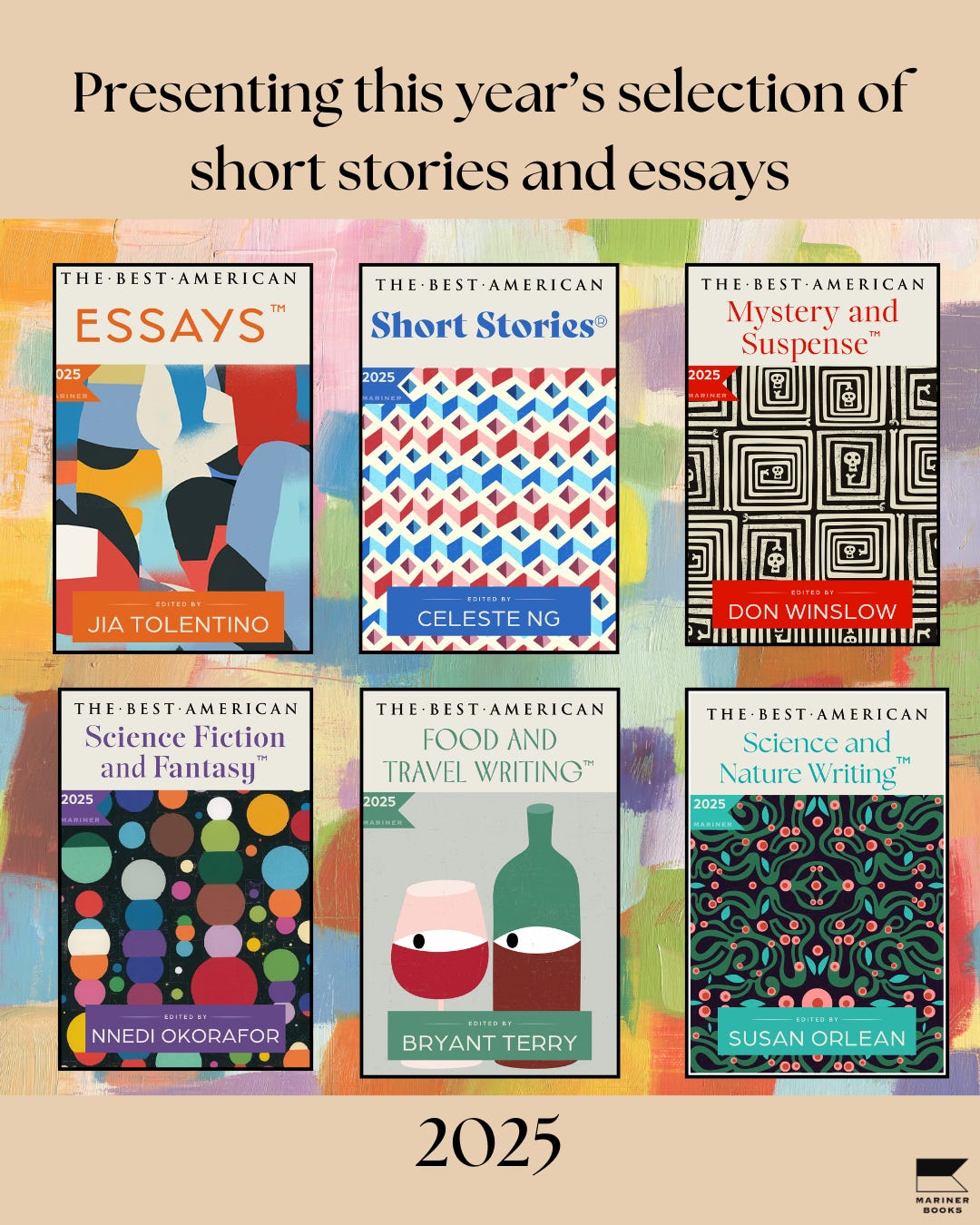

Last week the Best American Series announced guest editors and covers for its 2025 series, showcasing short stories, essays, science and nature writing, and food writing.

I’m honored to have a piece in The Best American Science and Nature Writing of 2025. The book comes out in the fall, but the Mariner Books marketing team is on top of it early, sending authors graphics to share:

Mississippi Reporting Extras

When I traveled to Mississippi, I brought my daughter, then 8, along on my reporting trip—visiting museums, cemeteries, and homes, and sitting in on interviews with elderly subjects in the story. She learned about this history along with me, which made this excursion particularly meaningful.

Here is a trailer from a 1985 documentary I also recommend, “Mississippi Triangle.”

The full documentary is also available online.

Details about the behind-the-scenes challenges of making this film in Greenville, Mississippi—especially when discussing Chinese and Black history in the region—got cut from my original story. So, I am also including those here:

Forty years ago, the release of a 1985 documentary, “Mississippi Triangle,” captured the local Black, Chinese and white racial dynamics in the region. In a 1987 Cineaste interview, filmmaker Christine Choy explained how they used three separate film crews—Chinese, Black and white—to gain access in Greenville. The Chinese community, for example, welcomed a film crew of Asian women into its churches and Mah Jong parties. “But there was one exception,” Choy explained. “They refused to take us to the Black-Chinese areas. No one wanted us to talk to the Black-Chinese woman who became a major character in the film.”

That woman, Arlee Hen, would grant interviews to a handful of researchers, historians, and filmmakers before her death.

Born in 1893, Arlee was also one of the children of Wong On and Emma Sing—the Greenville family I wrote about for Smithsonian.

During production, Choy’s film crew announced they were leaving town. Then they snuck back into Greenville, hid their car in an alley, and spent two days filming inside of Arlee’s home. She had married a Chinese man, J.S. Hen, who died in 1980 and was granted burial in Greenville’s Chinese Cemetery, a controversial decision, according to Ted Shepherd, a white pastor who conducted his funeral services and wrote about it in his book, The Chinese of Greenville. J.S. Hen requested that six Greenville police officers serve as his pallbearers, instead of local Chinese men, who he believed would have been ashamed—since he had married a Black and Chinese woman.

Arlee passed away in 1985, before the documentary was finished. Her recorded voice provides a haunting coda: “I couldn’t be buried in a Chinese cemetery,” she said. “And I couldn’t be buried in a Black cemetery.”

🔥