Learning to Trust the Making

Grace Talusan on where ideas come from

Classes are back in session, and so is The Reported Essay. I am excited to feature one of my favorite creative nonfiction writers, Grace Talusan, as our first newsletter guest of 2026.

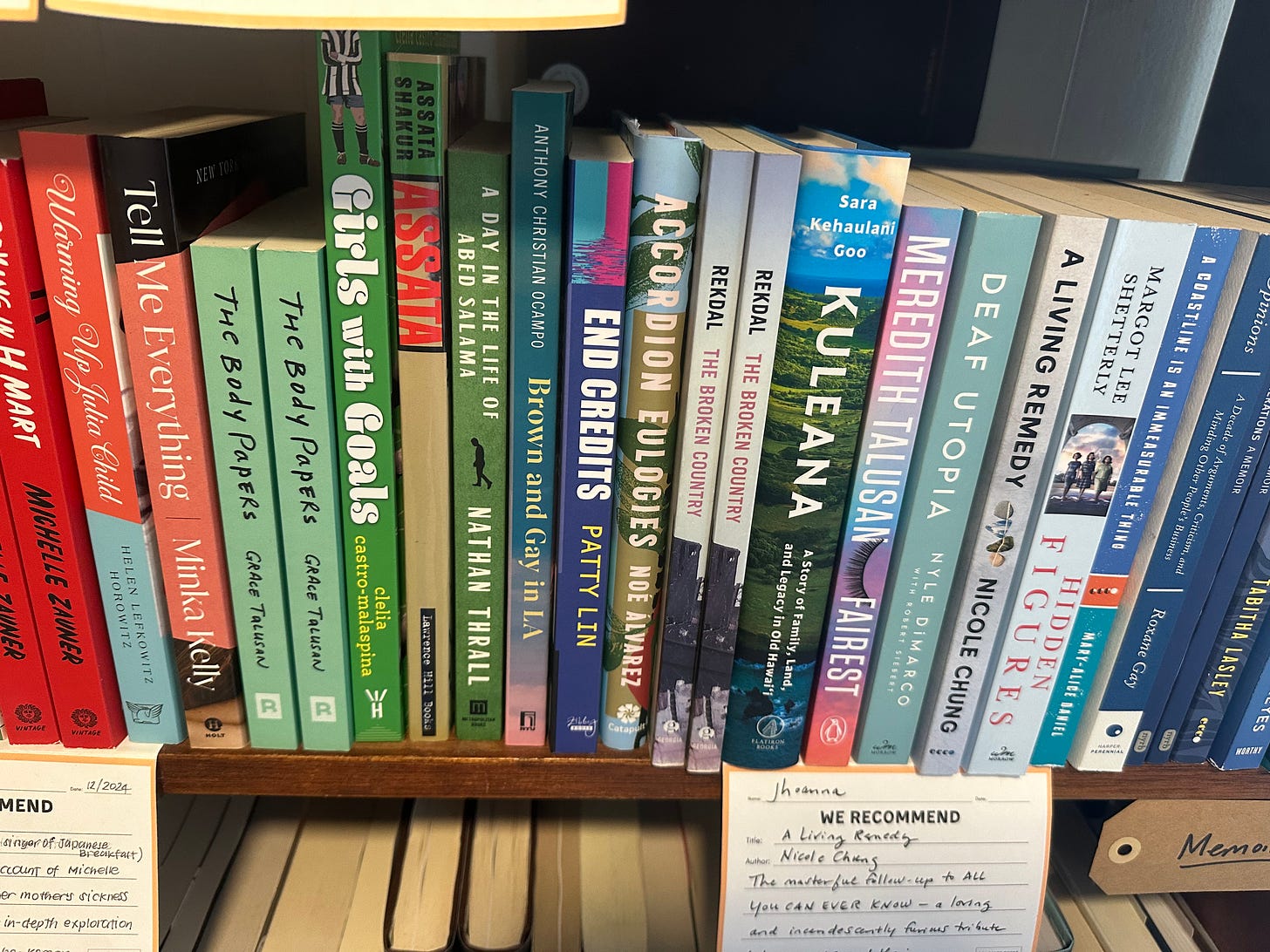

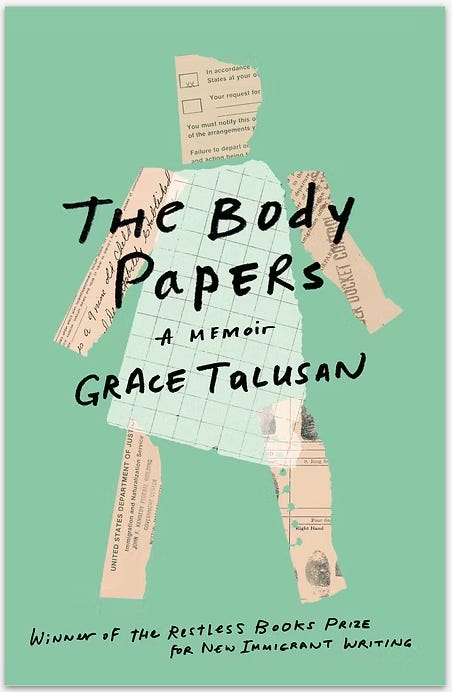

Grace is the author of “The Body Papers,” which won the Restless Books Prize for New Immigrant Writing and the Massachusetts Book Award in Nonfiction, and she serves on the board of the National Book Critics Circle (currently as chair of the Autobiography committee), which recently announced its Longlists.

For The Reported Essay, we talked about finding your way into ideas for essays and books. You can also read more from Grace over at Nieman Storyboard next week, where she spoke to me about teaching creative nonfiction and drawing from writing exercises that help her students tune into the world around them.

As an assistant teaching professor of English at Brown University in Rhode Island, Grace is one of several instructors who teach “Introduction to Creative Nonfiction,” the school’s most popular humanities class. Our conversation took place before the tragic shooting at Brown on Dec. 13th, when a gunman killed two students and wounded nine others.

When I checked on Grace after the shooting, she was still shaken and coming to terms with the devastating events. She now plans to re-introduce a class, “Writing Wonder, Joy, and Awe,” which she created a few years ago as a direct response to the students’ inundation with wars, pandemics, and climate disasters. She hopes it will help her students begin to process their emotions.

Writing nonfiction can be a way to explore trauma, memory, love, and looming life questions, but figuring out where to start can feel daunting. Grace tells her students to write freely in her classes. They never have to share if they don’t want to. She believes in the process and where it takes you.

On Generating Ideas & ‘Stranger Things’

My own writing workshop this week begins with talking about ideas. Where do they come from? How do you find them? I’ve written about finding the longform idea before. This year for the newsletter, I will continue to ask writers about the “story hunt.” How do they know when they have an idea that could be an essay, a reported feature, a narrative, or a book?

I also want students to think about themes they are drawn to. For me, themes are the existential questions we are forever grappling with. I’m interested in how writers seem to return to the same ones, even if the stories through which they explore these themes are entirely different and unique.

It took me years to realize that the same core themes seem to run through my work, whether it’s a profile, an essay, a science story, a narrative feature, or a book: coming of age, memory, identity, everyday people encountering surprising and remarkable circumstances. These themes are pulled from experiences in my own life, even when I write about other people.

One of the most popular coming-of-age shows in the zeitgeist right now (and in my household) is the Netflix series “Stranger Things.” I’m a parent of a middle schooler who loves writing fantasy fiction and is a new fan of the show. We had fun binging some of the series, starting with the pilot, over the break, while also watching a few Master Class episodes from the show’s creators, the Duffer Brothers. The screenwriters offered tips that echo Grace’s advice from our Q&A, about leaning on your own life, memories, and interests to generate ideas.

Nonfiction writers can learn from fiction writers, and one pointer the twins offer is to take some time to immerse yourself in the stories you love. For them, it’s movies and comic books. For nonfiction writers, this may include forms of fiction, nonfiction, longform, podcasts. The brothers then ask you to consider what connects all of these stories? What similar thread runs through them?

Next comes brainstorming. For the brothers, this involves letting your mind wander, listening to movie music, driving, taking a walk. It also inspires reflection. Thinking back on your life, moments with friends, stories you recall. At some point in this process for them, a merging of theme and plot occurs—the potential seed of a great idea.

The screenwriters keep lists of ideas, some good, some bad, kernels they may return to years later. I keep fragments of nonfiction ideas in my notes app—articles, random thoughts, themes, questions. Grace explores memories and life stories she has tested out by telling them to friends. The key, as Grace notes in our interview, is to trust yourself and the process, and to allow yourself the creative freedom to try.

Grace Talusan

Here is my interview with Grace, which has been edited for length and clarity. You can find her book, and others mentioned in this newsletter, on my Bookshop Page. And stay tuned to Nieman Storyboard next week for more writing insights from Grace.

Congratulations on turning in a first draft of your next manuscript. Are you allowed to talk about it yet?

The book is called “The King Died of Grief,” at least for now. The title comes from a misremembering of the EM Forster quote in Aspects of the Novel: “The king died and then the queen died is a story. The king died, and then the queen died of grief is a plot.”

It’s a book that just happened. It appeared while I was working on something else. Because I had been writing with a friend every morning, I had accumulated a lot of material from a project I thought of as “Essays I Will Never Publish.” I did publish some essays from that project and I showed my publisher this collection, but at the last minute, I said, “Oh, I just want to show you this other project I’m working on. I don’t know what it is.” And then my publisher was encouraging so I thought: “Okay, I’ll do it. I’ll see what’s there.” I still have a lot of work ahead of me, but the story is about death and the plot is that my cousin, the writer Meredith Talusan, led me to the book. Do you know Meredith?.

Yes, she wrote “Fairest,” and she’s actually talked to my UC Irvine students before over Zoom about nonfiction writing and journalism. But I don’t think I knew you were cousins.

I love that people don’t assume we’re related to each other just because we’re both Filipino and share the same last name, but Talusan is not a common name, so chances are good that I’d be related to another Talusan. So, Meredith and I didn’t grow up together and I’m older than her. We tried to figure out how to describe our relationship. Depending on which cultural context one is in, Meredith is my first cousin once removed because she is my uncle’s grandchild. In another context, I’m Meredith’s tita or auntie. At this point, we are friends and she is a beloved person in my life. We grew up in different countries and living separate lives, but we both became writers.

When my book was published, Meredith suggested we get to know each other and we started talking once a month. Then we ended up traveling to the Philippines together, and I was just following her around Bulacan, where my father and her grandfather are from. On the way out, we stopped at the San Rafael cemetery. She was going to visit her grandfather’s grave, and next to his grave was my grandfather’s grave. It was a surprising moment.

So the book is about that moment. The story of what that moment meant to me. The plot of the book is me standing at his grave for 25 minutes, which is not a plot, but something happens internally. Then the book goes in all kinds of directions.

I know that can be such a push to get to that point. What is your writing routine?

That’s a good question. My writing partner is Calvin Hennick. We are taking a break right now, but for three-and-a-half years, we were writing from 7:00 to 8:30 a.m. on Zoom every day, and then we would share what we wrote that day on a Google Doc. Now, I write on Zoom almost every day for a few hours with Alex Marzano-Lesnevich and intermittently with other writers such as Alysia Abbott and Gilmore Tamny either on Zoom or in person at public libraries and cafes.

How did you find your writing partners?

Calvin, Alex, and I are in the same writing group together, the Chunky Monkeys. Yes, the writing group that was written about in the “Bad Art Friend” debacle. We’re still meeting.

I remember you talking about how you wrote your memoir, and that writing group being essential to that process. A lot of people don’t have writing groups. They don’t have writing partners. They don’t know how to find community. Maybe you can talk about the process of finding writing communities?

The creative writing workshop I took in college was the first glimmerings of what is possible when you have other creative people around you. People who also care deeply about the same things you do, which in this case was writing stories. That’s when I first got that feeling of how important other people can be in a process that seems solitary. After the fiction workshop ended that semester, my classmates suggested that we still meet, get food, hang out, and read aloud our writing to each other.

And then, after I graduated college, I moved in with a poet friend, who actually is in “The Body Papers,” Joanne Diaz. As an aside, check out her podcast, Poetry for All. Within a month of us moving into our apartment, we wanted to be like Gertrude Stein and host literary salons. Our first one was a bust because we only invited people who lived in the apartment building, thinking we’d create community with them. No one came. And then we invited our actual friends and people who liked to write, not people who randomly lived in our building in Somerville.

Those salons were overflowing from our living room, and into the hallway and the bedrooms. They were very popular. People read from their journals and folded up pieces of paper. It was so fun. People read the craziest stuff. I still remember the absurdity of the things people read, and it didn’t matter if they were ever going to publish it because they entertained all of us.

Those literary salons were a way of creating a literary community, but it wasn’t a writing group. Before I went to UC Irvine for grad school, I took creative writing classes at Harvard Extension School mostly, and then a private class with a former literary agent. Those were fun, affordable ways to gather with other writers. My teacher at Harvard Extension School stopped me after class one day and said, “You should think about graduate school.” And I said, “What do you mean? Like medical school or law school? ” And he’s like, “No, no, you can go to grad school for creative writing.” I told him, “Oh, I don’t have any money.” And he said, “The best students will be offered full fellowships. They’ll pay for it.” I had never heard of this thing, that you could go to grad school and make a living and not have to rely on your parents or anything.

This was before the internet. I sent away for brochures through the mail and applied to anything in California. And then I got into UC Irvine, and that’s the life-changing point where I took writing seriously as a career, not just a hobby. At UCI, I realized: Oh, there are all these different ways I can build my life around my love of writing and my desire to write.

How did you shift to creative nonfiction or memoir, to write a book like “The Body Papers.” How did you make that decision?

Two things happened at the same time. I saw a call for Brevity, which was to write under 750 words of nonfiction and I was intrigued by the challenge of compression and writing something “true.”I was taking a weekend creative writing workshop, and in one of the generative writing sessions, I wrote “My Father’s Noose.” I am pretty sure that this was my first foray into creative nonfiction.

And then my toddler niece got sick, and I realized that creative nonfiction was a way for me to bring all these things together. She had eye cancer, and I did a bunch of deep dives into medical journals, reading all this stuff about eye cancer. It was just a way for me to contain and express my experience.

I wanted to talk to people when we were in the deepest parts of that eye cancer experience. Part of the way I dealt with it emotionally was by taking notes, which for some people who are not writers may sound terrible, but being really attentive to the moment is the way I got through it. That is the sound of her screaming because she is in pain, down the hallway. I cannot go to her because we are in the hospital, but I can attend to the sound of her screaming, and pay attention to everything that is going on around me.

So that is how I dealt with it, and then it became an essay that I published pretty quickly. I wrote it and Creative Nonfiction took it pretty fast, within a matter of months. That gave me feedback, which I think students, anyone, should pay attention to. Feedback. When you are writing, what is alive to you? What do you have so much energy for? What do you want to wake up early in the morning and return to? But also externally, what is actually getting published? Like, my fiction, I very religiously sent it out and it was rejection all the time, pretty much. But my Creative Nonfiction essay, it got snapped up immediately by a place I admired.

I also love the essay that you wrote recently, “How to Drown in America,” about almost dying with your now-husband.

Thank you. So I did write that as fiction first, and turned it into my workshop at Irvine at least once, if not twice, and it just didn’t work. Probably, what happened is some weird distancing thing was evident on the page, by writing it as characters in fiction. Also, that was in Irvine, a long time ago. I have returned to that experience and tried to write about it for various publications and in different-sized containers, but nothing worked. I even performed it as an oral story on stage at the Somerville Theater.

Then, a couple of years ago, a former writing student reached out from River Styx and asked, “Do you have anything?” And I was like: “What about this?” I worked on it with her editorial feedback and eventually found a way to finish it.

I love that you are talking about the different levels of privilege. And also just the fact that your husband did not grow up with swimming pools and lessons. You talked about how you make these comparisons. But also then you bring up yourself, like, how you had not thought about this. And so in a lot of first-person writing, we have to be honest about ourselves too. Was that something that came in the second draft too?

That was part of the more recent additions that would not have been there if I was younger. In the last couple of years I’ve been trying to explore my own complicity in all kinds of things. I’ve been digging in more deeply. I wrote “The Haunted,” too, about when my husband and I finally saved enough money and time to spend a week in Paris. We were so excited to go, but the trip didn’t go as planned and I ended up interrogating more deeply, “What does it mean for me to be Asian American?” Even within Asian Americans, there is so much difference in how people are treated, or what opportunities people get.

There was something there that happened with my husband, and also in the Paris essay, there is that part at the end that I could have never allowed myself to write until more recently, which is implicating my own anti-Black fears or whatever. Like, that moment at the end of the essay when I think, Oh, there is a man. I mean, is it because he is a man? Is it because he is a man of color? I do not know. But on a certain, just visceral, quick level, we are all taught to clutch our purse or whatever. And then it was horrifying that it was like, Oh my God, that is my husband. I feel terrible that I had that reaction. But there is something there about how we have taken in all these messages about race. And it is very clear about how we feel as a society about Black men.

That’s why I also appreciated your essays, because we’re sort of left out of the conversation of where we fit into this Black and white society, often. And then sometimes, we don’t even acknowledge our role in these systems, as Asian Americans, and how we’ve played a part in the inequities. All these things, we have to be honest about.

And the ways that we’re actually pitted against other groups. And then there’s the human part of survival, right? It’s like, “Okay, then that person can take the brunt of things, and then I’ll get away.” It’s very human.

Can you talk about how you moved from writing essays to books? Or your first book?

So during this 10-year time span, maybe even 15-year time span, after graduate school, after Irvine, I said I was working on fiction. I dreamed of publishing a novel someday, but the reality was that I was doing long-form journalism and publishing creative nonfiction. But what I said aloud is that I’m trying to write fiction and publish a novel without paying attention to what was happening, which is that I was writing creative nonfiction and what became my first book. So it is like this bifurcated thing.

I still want to publish a novel someday, but what happened is, I was on the Fulbright. I had a lot of projects. That is when my friend Joanne says, “But you have all this published, why do you not make an essay collection and call it ‘The Body Papers?’ Just do that.” And then I thought, Good idea. You are right. And since everything was published already and went through an editorial process with editors, I thought it would just be easy once the manuscript was accepted.

But once it was accepted, there was still like a year and a half of solid work, where I would dive in. We took things apart. So in some ways it was great. Take this one paragraph from this essay, and then throw the rest away.

So it became like a cohesive book. You did not just put the essays together and then you are done. You are making it into something else again.

Yes. And there was a switch. I got very frustrated. I was getting tired. I was working as an adjunct, so I was working a lot of gigs to make money. It was a very hard time. But there was one moment where something clicked in me, and I was like, Okay, I am going to edit this manuscript not for me anymore, but for the reader. What reading experience do I want a reader to have? And I thought about that and imagined it, and then that helped me make decisions from there about how to edit. My editor, too, but that just made things easy. I was like, what is the experience?

So how did you define that?

I wanted a propulsion. I wanted someone to feel like they just have to read one more chapter, you know. But how do you do that when you already know everything that has happened? It is not like the way a mystery would work. Like, how can I keep it positive and engaging, and also not too long? We cut lots out that I liked, that I wanted to say, but the book did not need it.

Yes. I appreciate that. I think there are a lot of long books out there these days that do not need to be as long.

It makes me sad, because I often read and think: Oh, if this were 100 pages shorter, then I would have really loved it.

Maybe they do not necessarily go through the editing or the groups to get that point of refining. But that is really interesting, just craft-wise, because you have these essays, you are putting them together, and you are thinking about an arc within a book. But again, it is not linear. It is not like the mystery, which is the classic kind of narrative journey, where you just have the arc. So then how do you work on an essay to make sure it draws the reader to the next section, if you are thinking that way?

So, I will say what I did for “The Body Papers,” and about essays in particular, I did all the mapping out of what I thought would be a memoir someday. I did all the things that people recommend. I read the Robert McKee book, “Story.” I learned from everything.

But the actual work of “The Body Papers” was printing everything out and moving things around once they were written. It was chronological first, because I heard that quote about New Yorker editors, like, you can turn your piece in, and then the New Yorker editor will just put it in chronological order. So it was that. Then what that meant was, “My Father’s Noose” was first, and then some readers were like, “I do not know if that is the place to start. What do you want the first note of this thing to be? You are going to scare people too early.”

Again, thinking of the book as a book, and what is going to be good for it. And so we had a writers’ group, and it was very late for me in terms of the process, but Celeste Ng suggested a move of a chapter. I think “Yogurt.” She was like, “What about if you put it at the beginning?” And I was like, Oh my gosh, wait, then I make a frame. And then I did it.

But I could not have pre-planned. That is at least part of my process and how I teach, which is: Allow yourself to trust that you will get there. But I could not plan it. I tried to. It just did not work well that way.

That is another advantage of having a group that you trust, because you are too in it sometimes to see that, or you never visualized this chapter over here.

The other thing that they helped me with in “The Body Papers” was that I was still really angry about a lot of stuff, and they could point things out and say, “I do not know if you want to do this. That just seems like revenge.” And I do not mean what you and I were talking about—interrogating oneself and one’s own contribution. It was actually nasty. I am so glad they told me about those points, because I do not want to be that person. It is fine that I wrote it. When you write it, then you can throw it away.

Being a writer, being a published author, that is power. I do not want to do that to somebody in a book. I do not need to do that to somebody. I do not agree with revenge or getting one’s feelings or grievances out in that way. I do not want to be that kind of writer.

Even though in the beginning of your book there are names you change, there is a fear of telling stories that you thought you would never tell, and then you realized at one point that stories needed to be told, and this is worth the risk. How do you teach and convey how to navigate that space of not bashing anybody, but still people are going to come away feeling uncomfortable, because how can you not when you are honest?

I try to be honest with my students about it. I mean, I was honest with them before, but I think things are changing. My husband works at a university. We live blocks away from where Rümeysa Öztürk was taken away after she wrote a group op-ed that appeared in the student newspaper.

So there is power in writing and this can sometimes come with real consequences. I do not want to scare my students, but I want them to be aware. It is different for everybody. Not everybody has the same privilege of free expression. We should have the same rights, but things are rapidly changing. We have to be careful.

I think of classrooms as sacred spaces. We want privacy. Of course, I also tell them that I am with the university, I am a mandated reporter. That is a responsibility I have, if someone is getting hurt or abused. But you can write freely in this class. You never have to publish it or share it or let your parents read it or anybody read it. You do not even have to let the other students read it. But I think it still is worth writing it.

Something could happen. Something could be transformed inside of you, or you could decide to publish it, and that is going to be very important. But I think it matters just to write it. I want people, if they decide to publish, to be thoughtful about where and how they are going to engage with publishing. My writing partner, Calvin, would get terrible threatening mail delivered to his home, handwritten after her published essays about race. He is white. His wife is Haitian. He has biracial children. One has to be more careful when engaging with the public these days.

Did the reporting part of essay writing come naturally to you? To draw on documents, to draw on archives, to do interviews. You said you’re taking notes on situations in your life.

Everything I did with reporting and journalism was all self-taught. I don’t think I ever took even one journalism class or had any formal kind of mentorship outside of the back and forth with an editor who assigned me a piece. I just started writing for the community newspaper when I was in maybe sixth or eighth grade, like middle school. I loved community newspapers. By high school, I was writing for an ethnic newspaper, the Philippine News Agency out of San Francisco. I loved doing it.

So you brought those skills naturally into your nonfiction. It sounds like it was just like it made sense to report your memoir. How do you then know something would be an essay? Like there may be so many experiences in your life, you’ve got all these things you’ve kind of jotted down, written in different places, but how do you realize it’s an essay?

I mean, in a few ways. One, because I’m telling my friend a story, and they might say, “You have to write that as an essay.” But part of what I’m doing is rehearsing the essay already. I don’t consciously know I’m doing it. I don’t realize until later, but I am testing the idea out to see if I can feel it. If I start taking notes on my notes app, if I have a document with a title on it, I already know that is going to start being an essay.

That makes sense, because there are these things that stick in our mind. These moments. There is a reason it comes back to you. And you start writing, and you might not know what it is. But then at some point that feels like it connects, or feels universal.

This is the journalism part, where you are trying to see if this moment is a good opportunity to add to the conversation. And I don’t mean like a hot take.

With the stories about your husband, how did you know those were essays?

Writing is how I process my feelings. That is writing for me and sometimes that turns into an essay. I think because I was so upset, I just was like, What am I going to do with these feelings? Let me transcribe my memory of what happened this afternoon. And so I think it just gave me something to do. I think writing is a coping mechanism for me. I mean, reading is too. My way of having privacy in the world. Everything can be going on, but I can be in my book reading. And I think writing is a way for me to be with people and not be with people at the same time.

It is all about trust and faith. Trust yourself. You just have to find that burrowing hole. Is it an image? Is it a taste? Is it the scene? You are only going to find out by sitting down and doing it. And you are not going to know, until you make it, if it is going to hold together.

Such a great interview. I love Grace's work!