Journalist Donovan X. Ramsey on 'Building Something New'

A conversation for our times with the author of 'When Crack Was King.'

My students started reading Donovan X. Ramsey’s excellent book, “When Crack Was King,” in the lead up to the election. They discussed its opening chapters on the same day that so many of them stood in line for up to four hours to vote. For most, it was their first time casting a ballot.

In class, they had been thinking about how Ramsey portrayed crack itself as a fifth central character in the book, which focuses on the lives of four human subjects. Ramsey braids their deeply reported stories into a narrative chronology that traces the rise and fall of the crack epidemic in the United States.

As one student wrote in a response: “Ramsey zeroes in on the roles the Nixon, Reagan, and Bush administrations played in shaping the war on drugs, highlighting how these policies led to mass incarceration rather than rehabilitation...”

“I was getting chills reading it,” wrote another. “I saw so many parallels with the present day, especially when Ramsey was describing the election between Nixon and Hubert Humphrey.”

Ramsey had generously agreed to speak to our class via Zoom long before we had any idea of what the results of the presidential election would be. But he could not have visited at a more necessary time. One week post-election, Ramsey offered words of wisdom to young journalists—advice I also really needed to hear.

“Hopefully we will survive this, and maybe the goal is building something new. We as journalists do the work of looking at history and connecting with people, because we're trying to find possibilities for something new.” —

He was kind enough to agree to share our Q&A with you as well. I hope you also find inspiration in it. Each of the questions below came from the students themselves. Thank you to Ramsey for being our professor for the day.

Ramsey’s reporting has also appeared in The New York Times, The Atlantic, GQ, WSJ Magazine, Ebony, and Essence, among other outlets. He has been a staff reporter at the Los Angeles Times, NewsOne, and theGrio. He has served as an editor at The Marshall Project and Complex. He holds degrees from the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, where he concentrated in magazine journalism, and Morehouse College in Atlanta.

“When Crack Was King” pairs well with “Rosa Lee,” a book I first read when I was an undergrad studying journalism. It was written by a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and professor, Leon Dash, who I came to know and respect from my alma mater. A pioneer in immersion reporting, Dash drew from ethnographic techniques to tell the story of “Rosa Lee,” which traces the life of a drug-addicted woman and her family’s life in poverty in the 1990s. I’ve taught Dash’s book in the past as well, and it makes for good discussion about ethics and immersive journalism.

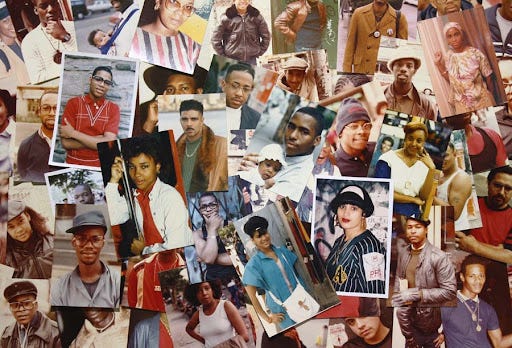

Ramsey’s sweeping and compassionately reported book takes an intimate and panoramic view, beginning in the 1960s, and taking us into the lives of four people, Lennie, Shawn, Kurt and Elgin, through history and into today.

Here is our Q&A with Ramsey, led by the students:

Did you ever consider establishing yourself as a first-person narrator for the entirety of the book? And if so, why did you decide against that?

I didn't study journalism in undergrad. I was a psychology major. So all of my early training came from my graduate program in journalism, and I was taught to never write yourself into the piece. I had a professor who was just old school: “You should never be in the story.” That voice has always been on my shoulder. So when I wrote the book, it was without the foreword or the afterword, which mentioned me growing up. I realized that in writing the book, something was missing. Actually it was useful to explain to the audience why I cared about this subject. I wanted the audience to trust me as the narrator.

So I just decided that I would explain how I met each of these remarkable characters, and what my observations were of them, but also why the subject matter was important to me. I did consider writing myself more into the story, explaining where I was in my life as the crack epidemic rose and fell, but ultimately, I thought that putting myself in the foreword and afterword was the right balance. Journalism is changing, and the needs of journalism are changing, and one of the needs, I think, is for us to be more transparent about the process. So writing about yourself is, I found, one of the ways of being more transparent.

I read Act Four after election night, so this was difficult for multiple reasons. Since the results came in, I've been struggling to stay positive and remain hopeful for the future, but it's been really hard. I want to use my role as a journalist to uplift others, especially those in the queer community. I find your motivation behind this book—to uplift your community and deconstruct the stereotypes and myths—so painfully relatable. My question is how did you approach your four main subjects? How did you begin to think about structure for this very big, difficult story?

The story is about this terrible period in history, but it's also about how people survived that. History does not repeat as much as history rhymes. I think of history not as a straight line, but almost like a spiral. So we're moving forward, but we're coming back to familiar things. I wanted to remind people, even when they're at some of the ugliest parts of the history, and the personal narratives of Lennie, Shawn, Elgin and Kurt, that all of these people survived it.

So going into structure, that’s why the story starts with us meeting them in the present day. I wanted people, as they're reading, to know something terrible is going to happen to Lennie or to Shawn. But you have to remember that you met them in the present day, at the beginning of the book. So they're going to survive this. You don't spend the entire book thinking, “Oh, my god, is this person going to die?” Some of the feedback I've gotten from people is: “Well, not everybody survived the crack epidemic. Why focus on these survivors?” I think we have something to learn from survivors. They came out of it with some scars, but they have some incredible insights from what they survived that are worth lifting up and celebrating. So when history does come back around, we can actually learn those lessons.

I modeled that based on the HBO show the “Watchmen,” which is about superheroes. I realized in watching that, every superhero has a origin story that is about trauma. Superman’s family sent him in a spacecraft to earth, because their planet is being destroyed. Or Peter Parker gets bit by a radioactive spider. That's traumatic. You meet them as a superhero, and then you learn about the trauma that made them a superhero, and how they've navigated it. I realized that each of my characters was a hero in some regard, in that I had to put them in the present day in their cape, and then you learn the story of how they got there. Even writing nonfiction, we can steal from fiction.

Do you think your own background allowed you to step in your subjects’ shoes a bit more, or do you think that made them more comfortable sharing these very vulnerable moments with you?

That’s a really important element of the reporting process. How you situate yourself and your identity, both the reporting and the writing. Again, I was taught to lean away from that, but I think that we are entering a period in journalism where you can never avoid your history and your identity in the work that you do. That was always a fallacy of the sort of unbiased journalist who is very neutral, and it's something that really centers white men who are seen as neutral identity-wise. Over the years of reporting leading up to the book, I had to free myself of this idea that I was supposed to ignore and hide and compartmentalize where I came from. Because it binds you up, to not lean into your expertise.

I got to a place in my reporting where I realized I've been a Black man a long time. I know a lot about being Black. I'm from a Black family. I grew up in a Black neighborhood. I went to a Black college. Instead of trying to act like that doesn't exist, I'm going to lean into that. A part of writing this book actually was a reclamation of myself saying: “I can be a legitimate journalist, writing about stuff that impacts me and reflects my history, as much writing about, say, the economics of agriculture,” which people would have you think is some higher duty and calling as a marginalized person. As if writing about yourself is somehow easy or less. No, it's actually very hard. So I want to encourage you all to not spend as much time as I did struggling with that fallacy. It makes the reporting so much easier when you're leaning into who you actually are.

It's a part of why I wrote about also meeting each of those characters. I had to sit down with Lennie, who spent years in her addiction, and be able to earn her trust. For her to know that I wasn't coming from a judgmental place, the way that I did that was to say: “You remind me of ladies in my neighborhood. There's something that we have in common.” To not reflect that in the writing, again, wouldn't be transparent.

Every journalist has their tricks of gaining a source's trust, and a lot of times we don't write about those tricks. So it was also a pleasure to say: “This is how I got these people to talk to me, and to be transparent about that.”

What was the process of research, interviews and writing like for you, and how did it impact you emotionally?

Growing up in a space with lots of trauma, lots of family conflict, I had a tolerance for trauma. It's a part of why I do the kind of stories that I do, because a lot of people look away from or can't handle other people's mess. We as journalists sometimes put ourselves in positions where we're doing that work in communities, writing other people's stories, just trying to make sense of it. I've always had a big tolerance.

What I didn't realize, though, was that you’ve got to have breaks. I'd always written longform stories, 3,000 to 4,000 words. That gave me enough time in between stories to recover. Well, I spent five years writing “When Crack Was King,” so I was in it even when I wasn't working on it. It was playing in my subconscious. Also because there are elements of it that were personal, about the neighborhood that I grew up in, and the folks in my community, it brought up a lot of stuff. I didn't realize it until I would sit down and type, and I would wonder: “Why am I always so itchy every time I sit down to work?” Maybe it's the coffee that I'm drinking, or maybe there's mold in this coffee shop where I'm working. I was breaking out in hives. It took me actually getting through the book to realize that I was working through my own trauma, and I was also processing with my sources in real time their traumatic memories, as we were trying to make sense of it by putting it into narrative.

You have to recognize, the first step is recognizing that you're doing that work, and you're not just some emotionless robot scribe. You're a real person that's really in it, and that you have to care for yourself if you're going to take on those kinds of stories. That means seeing a therapist. Exercising. I got into yoga during that time, because I realized I hold my breath when I get anxious. Just trying to find joy. Life is not all doom and gloom. Even serious subjects have beauty, fun, and levity in moments. Lennie, who's one of my sources in the book, was an addict and a sex worker for decades. She is one of the funniest people I've ever met.

Also, I want to say something, because I can feel the heaviness of this election and the sort of scariness on y'all. I feel it too. Not to be preachy, but this is what I tell myself: There were over 60 or 70 million people that voted for Kamala Harris. She raised over a billion dollars for her campaign in a handful of months. That may not be enough to win an election, at least in this climate, but you can do a lot with 60 or 70 million people. That's 1/5 of the entire U.S. population. Elections aren't the only things that matter. How we put together a society, and how we take care of each other, that is important. Being engaged in building community. If 60 million people is all that I can get to be allies, I'll take it.

It might feel like it’s the end of America, which is scary. But a part of me feels like, as a Black man in America whose ancestors have been here for seven generations—many of those generations being enslaved—I think my ancestors are cackling on the other side, knowing that this thing is coming to an end, and there might be something else on the other side of it. So as much as we want to hold onto the hope and the promise of trying to reform this country and this government, if it all comes crashing down, that doesn't mean the end of the world. It doesn't mean the end of us. Hopefully we will survive this, and maybe the goal is building something new. We as journalists do the work of looking at history and connecting with people, because we're trying to find possibilities for something new.

I want to create a document that people can pull up when they're building a new America to say: “Let's dust off ‘When Crack Was King’ to see how not to do it again.” That's the work that we have to do. Good, honest journalism that helps people make better choices. That means reflecting the history, but also showing the possibility.

We were talking about trauma-informed reporting, and I was curious, how do you approach your subjects to make them feel more comfortable? Was there anything that you specifically learned?

I think it's really important when dealing with people who have experienced trauma, that you go as slow as possible because you don't want to re-traumatize. You don't want to trigger people. You want to allow them to share at their own pace. That means also you have to do a lot more interviewing than you would otherwise, because you're going slow. People who've experienced trauma often have fractured memories, because trauma takes you out of your body. So in those moments, in their own personal histories, they might not have full memories of events, and it might come to them in fragments. So you have to be patient with that. But also there is possibility in that.

Every struggle that you face in your journalism is also a chance to do something new. So I found that with Lennie, for example, she didn't remember much of her 20s because she was high for a lot of her 20s. So that was an opportunity for me to write what she could remember, but to then fill the gaps in her memory with the stories of other women like her, to write about what life was like for Black women, addicts in the 80s, or for sex workers in the 80s.

Lennie may not know what happened between 23 and 27, but that might be, even from a creative writing perspective, a way to think about how you can present somebody's history in fragments. One of the reasons why the story takes the shape that it does, with these chapters of personal history woven through the history of the crack epidemic, is because that's how our memories work. It’s not just one big linear story. It's vignettes and scenes. We think about what else was happening in the world, and then we think about something personally that we went through. I think that this goes back to some advice that an editor at One World gave me, which is that a book can be whatever you want it to be. It should be whatever you want it to be. You don't have to follow any rules. Longform journalism is the same. A longform story should be whatever you want it to be. You have the opportunity to get creative.

What goes into writing a nonfiction book, because longform is different from short articles. So how did that experience feel for you, and what can we take away from that experience in our own writing?

It was the hardest thing I ever had to do. I have always loved magazine writing and always wanted to write a book. The thing about writing a nonfiction book is that it has to be a topic big enough. One you want to talk about for the rest of your life. I will be the “crack guy” for the rest of my life. I didn't think about that. So that's one thing. The other thing is that it has to be something where you can go down a lot of different rabbit holes. A topic where there are so many tentacles to it. I just want to connect all of these loose strings for people. That's a great reason to write a book. Also for me the crack epidemic was a story that was on the tip of my tongue. Whenever I talk to people about the system we have, I would say: “How did we get here?” And they would say: “The crack epidemic.” Everyone had an understanding of it, but nobody agreed on what it was. So for me, I thought, this is a reason to write a book.

One of the reasons why the book is structured the way that it is, with so many different little chapters interwoven, is because I come from a magazine background. I can write 4,000 words without getting tired. But I do get tired after 4,000 words. I thought: “I'll just write it as a series of magazine stories and piece them together.” That was my hack, and also hoping it would give the readers breaks.

I was just wondering what kind of skills or experiences do you feel are most important to develop your voice as a writer? And were there any challenges specifically when writing this book?

I love interviewing. It is my favorite part of the journalistic process, because I am such a talker, as you can tell. I grew up in a family of gossips, liars, and jokesters. So we all are talkers. For me, that's the thing that comes easiest to me. Some people love collecting research and literature, and then analyzing and making sense of it. I would say Malcolm Gladwell, he’s that kind of writer. You can tell he loves that part of the process.

Some people love shoe leather reporting. Being out in the field and just gathering details about what they're seeing and who they're talking to. Some people love the editing process. You may not love writing, but you might like working with someone to find the right word or the most beautiful sentence. For most journalists, we like one part of the process, and we put up with the rest of it to do that thing. I put up with writing and editing so I can interview people. I put up with research so I can interview people. In order to keep doing the work that is fulfilling for you, whether it's a short form story or a longform story, make sure that the part of what you love is in it. For me, if I have to write a story where I can't interview people, it's a pain, it's going to be slow. I'm not going to like it. I'm going to beef with the editor in editing. I'm a Leo, so I'm dramatic. I'm a little bit of a baby, so I act up if I don't like it.

I think the book process made me better at editing, and it also made me a better researcher, because it is ultimately a history book, so I had to make sure that the history was accurate, that I did justice to the events, to the political history, to the social history. Also I did something I wouldn’t typically do: I showed the history chapters to historians, and asked them to read and be in conversation with me, so I could fill in gaps in my understanding. It's part of my research process now. Actually running it by experts in ways that I wouldn't before, so that it's as tight as possible, because information is becoming more contested.

When you're reporting and writing a story, how do you handle situations in which people do things you don’t necessarily agree with, or what if a story changes on you?

Going into this book, writing about Shawn and Kurt, I had very different ideas about them. Kurt was a mayor, and I tend to be a little anti-authority. But Shawn was somebody that had been a drug dealer, despite having basketball scholarships and being a college student. Both of those people, I knew that I needed to tell their stories, because I wanted to represent all perspectives. But they rubbed me the wrong way because of my personal stuff. Like, “Shawn, you were a knucklehead, and you made poor decisions for a good part of your life,” and it got on my nerves. A lot of people love Shawn as a person for that reason. He annoyed me, and I hated writing about “here’s Shawn making another stupid choice.” Even the whole thing with Kurt, who was a mayor, and who was, from a policy standpoint, against criminalization, but who was also completely down to use the police.

Some of the best advice I got from a mentor is that, as a journalist, when you're dealing with sources you have to take them seriously as people. You can't allow them to become “characters.” What I found that to mean is that even when you don't understand, appreciate, or respect someone's choices or thought processes, you have to imagine there's still a real person who is coming to that conclusion because they think that it's helping them or somebody else, right? That's who we are as people. Always keep in mind that every individual, famous, not famous, powerful, not powerful, has emotions and ideas of their own that are guiding their choices. Even when they do things that you don't like, or they go in directions and you're thinking: “Why are you going in that direction?” That will help you stay anchored to something that's real. Why are they making this choice? Stories can be messy. They don't have to fit into any boxes. Sometimes things won't make sense, and there will be characters who do things that you don't expect or don't like, events that you don't see coming, and that just adds to the reality of a story.

You touched a little bit on the empathy you had for Lennie, for example, and then your annoyance having to write about Shawn multiple screw ups. So I was wondering, despite your upbringing during the height of the crack epidemic, what biases were you forced to confront in writing a book?

I was certainly raised with a bias against addicts, and I realized that in putting together the book, I grew up being afraid of people who had addiction. We were taught through Dare and Just Say No programs that “those people are like zombies,” and by associating with them, you were willing to become one of them. Essentially, it didn't make any sense, but I grew up with that fear.

I also had a bias against people who make poor choices. I was raised to think you have to stay on the straight and narrow, and that people who make poor choices are left to their own devices, and whatever happens to them happens to them. But that was countered by the fact that I had addicts in my family. We had neighbors and members of our community who struggled with addiction that were still part of our lives. So how could I think Lennie was a zombie when I had a neighbor two doors down who was an addict, who I saw, and loved her daughter, who goes to church every Sunday with her mother?

A part of the job of being a good journalist is questioning everything. They say: “If your mother says she loves you, get a second opinion.” If someone says: “People started using drugs because they were just prone to using drugs,” as journalists we’ve got to say: “Wait a minute, is that true? Why is that true?” That is the antidote to stereotypes and ideology. Taking people seriously. Assuming that every source you come across is a human being just like you. A person who probably wants to live a good life and do well. That opens up your imagination for who they actually are. Not just not taking easy answers.

Also, over-report everything. You know that old professor in grad school that I was telling you about who told me to never write myself into a story? A great piece of advice he did give me is that if you have five voices in your story, you should have interviewed 20 people. There should be this whole host of folks who didn't make it into your reporting, who were just there because maybe they weren't the right voice, but they are supporting what the main person is telling you. I have four characters in the book, but I interviewed hundreds of people.

I traveled throughout 2018 to the 12 cities that were hardest hit by the crack epidemic, and I spent about a month in each of them, walking the streets, talking to people who were dealers, who were addicts. I felt comfortable presenting Lennie because I had talked to lots of women like Lennie, and I thought that she encapsulated so many of their experiences. You'll find lots of people who fit a demographic, statistically, and can be a character in your story, but they might not be good talkers. Always go with the best talker. You'll make it easier for yourself. If you come across a person who is just charming and witty, and has a way with language, always go with them. Lennie's a great talker.

Your method of implementing both narration and bits from your interviews was really well done. How did you find that perfect balance of implementing both?

It was hard. I am very practical about writing. So as much as we want to have fun and be creative, I've always told myself that journalism is like being a grocer. You’ve got to get the merchandise out before it goes bad. You can't sit on a story forever until it's perfect. We're doing service work. I had, in my book contract, a 100,000-word word limit. I said I want the book to be a balance between personal narrative and history. It was not enough for me to just present the history if we didn't talk about how the history actually played out in people's lives. So very practically, I said: “I need to write at least 50,000 words in history, and then 50,000 words of their personal narratives.”

So all of my research and reporting during that year that I was traveling involved writing the 50,000 words of crack’s rise and fall, getting a good sense of what happened to crack as a character, then putting that in multiple chapters. Then splitting that other 50,000 words between the four characters that I settled on, and trying to give them equal weight.

That’s about 10,000 words per character, give or take. Ultimately, in the end, then piecing it together, trying to find the connective tissue. When you're doing a story that has that many elements, parts, different voices, and characters, chronology is your friend. The only thing people have to hold on to is a timeline. So I knew that the story had to go from the beginning of the crack epidemic to the end. That was the spine of the story. Crack’s rise and fall.

Then I looked into that and said, “Well, what was happening in Lennie's life at this time? Is this the right place to put a Lennie chapter? Kurt was involved in this policy, around this time.” It’s a spine that breaks off into all of these little nerves. Then after those were in place, I thought: “Oh, wow, these characters are in conversation with each other.” There are places now for me to think about moving their stories together, pairing them in some areas. Ultimately, that is how the story came into the structure that it did.