Humanizing History

A conversation with New Yorker editor Michael Luo on his new book 'Strangers in the Land'

In the introduction to Michael Luo’s Strangers in the Land, he tells the story of an encounter in 2016. When he was standing in the rain with his family in Manhattan, a woman yelled at him: “Go back to China!”

That incident, which Luo also wrote about in The New York Times, coincided with Trump’s election to office for his first term as president, and would be followed by a wave of anti-Asian violence during the COVID-19 pandemic, part of a growing “tinder of racial suspicion,” he writes. His monumental new book grew out of these events, but the seeds of it seem to have been stirring inside of him—as these enduring questions about our place in society often do—long before he began to research and write.

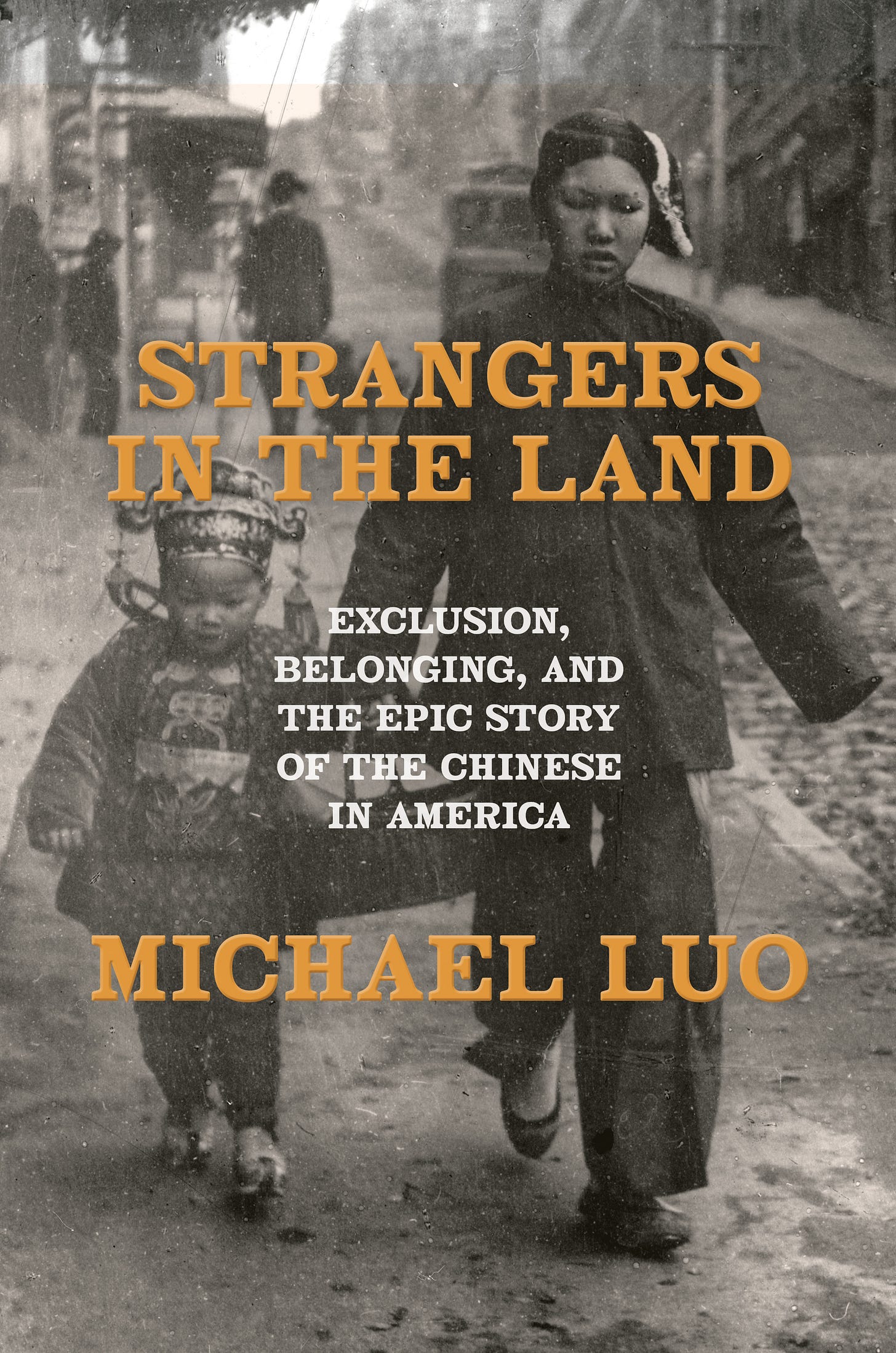

Strangers in the Land, released in April, documents Chinese immigration and exclusion through a tapestry of human stories unearthed from the archives. It is about people with dreams, fears, flaws, hopes, and incredible struggles.

I recently had a chance to interview Luo about his process of reporting and writing this narrative history. Luo and I have both thought and talked about Robert McKee’s famous book Story, how the screenwriter maps out rising and falling action, tension, and character development. Luo’s book follows the arc of history, and the people living and dying along this tumultuous journey.

I was born in the Midwest and spent my childhood and middle school years in an Illinois town surrounded by cornfields. There were few Asian Americans in my neighborhood, and for a period I put up with the “go back to China” taunts and racial slurs daily. By high school, I had moved to a suburb of Seattle, Washington, where I encountered many more Asian Americans and immigrant groups. But I also remember being 15, and feeling absolutely starved for history about race and minority groups in America.

Not receiving this kind of learning in my own classes, I remember digging through libraries on my own, devouring whatever books I could find from the perspective of people I did not hear from in my own classes. I sped through The Autobiography of Malcolm X, Nisei Daughter, and America Is in the Heart. One day, I picked up Ronald Takaki’s Strangers from a Different Shore, finishing it in between my actual class assignments on European world history and the Cold War.

I couldn’t believe no one else had told me before then about the Chinese building the railroads, some of them freezing to death, not to mention the harrowing stories of incarcerated Japanese Americans, the plight of Hmong refugees, or Filipino laborers on sugarcane plantations in Hawaii. I closed the book feeling like the racial slurs of my middle school life suddenly had inciting incidents.

“True character,” as McKee writes, is revealed “in the choices a human being makes under pressure—the greater the pressure the deeper the revelation.” McKee asks what exists beneath the surface of characterization. At the heart of humanity, “what will we find?”

In Strangers in the Land—the kind of book I wish I had a chance to read when I was a teen searching for more illuminating stories like this—the Chinese immigrants are the collective protagonists of the story. Through them, and the unbelievable pressures they endure, we see their true character emerge, and we see America’s as well.

So, I hope you enjoy our Q&A, which took place at the San Diego Central Library, and has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Luo is an executive editor at The New Yorker and writes regularly for the magazine on politics, religion, and Asian American issues. He joined The New Yorker in 2016. Before that, he spent thirteen years at The New York Times, as a metro reporter, national correspondent, and investigative reporter and editor. He is a recipient of a George Polk Award and a Livingston Award for Young Journalists.

Mike also graciously answered a few bonus questions for The Reported Essay (at the end), for any of you writers who aspire to pitch or publish in The New Yorker.

When reading Strangers in the Land, it feels like an odyssey. It is the kind of book you should keep on your shelves for future generations to read. So I’d love to start with how you came to report this epic story.

The personal story I tell in the introduction of the book happened in the fall of 2016. It was October, a couple of weeks before the election. Trump was about to be elected, something that would shock the world. We didn’t know it then, but you could feel a kind of curtain of nativism descending over the country.

A group of us Asian Americans friends had just left church. We were standing on the sidewalk on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, and a well-dressed woman brushed past us. She looked like a typical Upper East Sider, she could’ve been my neighbor or a parent in my daughter’s class. She muttered loudly, “Go back to China.”

It was after church, but I didn’t turn the other cheek. I actually abandoned my daughter in her stroller and ran after the woman. We exchanged words. She yelled back something like, “Go back to China!” My adrenaline was pumping. All I could think to shout was, “I was born in this country!” And I yelled it down the block.

Later, I tweeted about it. This was 2016. And I used the hashtag #thisis2016, lamenting the fact that something like this could still happen. The tweet thread went viral. I remember Bill de Blasio, the mayor of New York at the time, even tweeted back, saying something like, “Mike, you’re always welcome in New York.”

As I walked home, pushing my daughter in her stroller, I felt this overwhelming sadness. I wondered if my kids, who are two generations removed from the immigrant experience, would ever truly feel like they belonged.

That moment in 2016 didn’t lead directly to the book, but it started a personal journey—thinking more deeply about my Asian American identity and the history of the Asian American experience, much of which I honestly didn’t know.

Then came 2020, the pandemic, and in the spring of 2021, the Atlanta spa shootings happened, when several Asian American women were killed by a white man. Whether or not it was explicitly a hate crime, it triggered a wave of anti-Asian sentiment and violence. I wrote a piece for The New Yorker that looked back at the 19th century, particularly at a period I had never heard of before—the “driving out” era of 1885–1886, when nearly 200 communities in the American West physically and violently expelled Chinese people.

That piece led to this book. The more I read, the more I realized how relevant it all felt. The sense of precarity that defines the Asian American experience has never really gone away, and that became the core idea of the book.

Rachel Swarns was a staff reporter you worked with when you were an editor at The New York Times, and I heard her speak about The 272, a book she wrote on the enslaved families who helped build the Catholic Church. She said you once told her: “This is investigative journalism with history as its canvas.” And it really feels like, with this book, you took your own advice. Could you talk about how you blended investigative storytelling with historical depth, and also that human aspect?

Investigative reporters generally fall into two camps: source people and document people. The first build relationships, like Woodward and Bernstein in Watergate. I’ve always been more of a documents guy. In that way, being a historian felt natural. It’s essentially investigative reporting through documents.

On the storytelling side, I see myself primarily as a storyteller. I think of someone like Rick Atkinson, a former Washington Post reporter who wrote an amazing World War II trilogy. He’s sometimes criticized for not making arguments, just telling stories. I read an interview where he responded, “Guilty.” That resonated with me.

For me, though, I am trying to make an argument through the stories. The New York Times ran a wonderful review of my book, and what I loved most was how they highlighted the characters. In the archives, I looked for opportunities to find actual people, especially since the voices of Chinese people are often missing. History is written by the powerful, but if you dig deep enough, the powerless are still there.

I thought of the Chinese people as the collective protagonist of the book. Every chapter had a character or a set of characters to anchor it. Some reappeared across chapters to help tie the narrative together. It was really important to say their names. People who often went nameless in history. And to paint them as fully as possible.

Chapter Five really stood out to me, it reads like a movie script unfolding. You also list every name from the Chinese Massacre of 1871 in Los Angeles, along with a detail about them. It’s an event I had heard of before, but never in detail like this.

The 1871 massacre is largely unknown, even though it's the worst mass lynching in American history, with 17 Chinese victims lynched, and an 18th killed differently. And it didn’t happen in the South; it happened in Los Angeles.

To write that chapter, I gathered around 300 sources. Newspapers, manuscripts, documents. I compiled them in a folder. Then I created a chronology in Evernote, breaking down the events piece by piece. One document was a coroner’s report published in a newspaper. It listed the names, often Anglicized, and sometimes gave a bit of detail. I tried to bring as much life and dimension to them as possible.

One figure I focused on was Gene Tong, an herbal medicine doctor and one of the more well-known victims. He spoke English and had a business that served white customers. Classified ads showed he rented office space from a white furniture dealer. He had a wife, a roommate, and a pet poodle. That poodle detail came from a reporter who visited his ransacked apartment after the massacre. The building was covered in blood and torn apart. Under a table, they found a poodle with a broken leg, whimpering. I included that. It made the loss feel real.

Those narrative details—the poodle, or the clotheslines that became a noose, or the sandals and shirt placed in the coffin—bring this history to life. But parts are also very painful to read. How did you manage the emotional weight of that?

I was conscious that it couldn’t be a relentless litany of violence. That kind of repetition causes the emotional impact to dull. Early drafts were overloaded. Massacre in L.A. in 1871, riot in San Francisco in 1873, rural violence. It was too much.

So I made space for breathing. I expanded a chapter on the legal battles over citizenship, how Black Americans were granted access to naturalization after the Civil War, while Chinese immigrants were still barred. I also focused on individuals like Yung Wing, the first Chinese graduate of an American university, Yale in 1854, who brought Chinese students to study in New England. These chapters allowed readers to step back and take a breath before returning to the heavier material.

When you were in the archives, did you ever wonder if you were the right person to tell these stories? Or did any particular name or story call to you in a personal way, where you thought, “I have to tell this”?

What’s actually interesting is that while my family's story is part of the post-1965 wave of immigration, the heart of my book focuses on the 19th century. It’s a narrative history of Chinese exclusion, starting with the Gold Rush and going through the 1960s, when my parents came to America.

Most of the Chinese immigrants in that earlier period came from southeastern China, the Pearl River Delta, in Guangdong Province. They spoke Cantonese or dialects like Taishanese—languages different from the Mandarin my parents speak. So in some ways, I felt a distance from that history. When you look at photos of those immigrants, they look different. The men wore queues, the traditional braids required by the Qing Empire, which made them seem foreign to me.

But as I immersed myself in the research, I began to connect with their experience as "strangers in the land." That phrase comes from a Supreme Court decision that upheld one of the Chinese exclusion laws. In 1882, Chinese laborers were banned from entering the U.S. in what we now call the Chinese Exclusion Act, though it was actually a series of laws. In upholding it, the justice described the Chinese as “strangers” and said they would never assimilate.

I can relate to that feeling of being perceived as a stranger. And it’s not just about the Chinese. Many immigrant groups have been, or still are, treated as outsiders. I say this in the book: it’s really the story of our diverse democracy. It’s the story of us.

The opening epigraph of the book is from Charles Yu, the novelist who wrote Interior Chinatown. It’s an incredibly imaginative, powerful book—it won the National Book Award in 2020. If you haven’t read it, the main character is a background actor in a cop show about a Black cop and a white cop. His role is “Generic Asian Man,” and his greatest aspiration is to become “Kung Fu Guy.” There’s no space for a fully realized Asian American character.

The epigraph comes from an imaginary courtroom scene in the book where the character is asking, “Who gets to be an American?” That’s the central question of my book. I didn’t quote this part, but the character goes on to say, “We keep falling out of the story, even though we’ve been here for 200 years.” That’s why I wrote the book. Asian Americans have been here as long as many European immigrant groups, but we keep falling out of the narrative.

Earlier you talked about gaps in the archive not meaning silence. You also bring in white historical figures like Denis Kearney and William Speer. Can you talk about how you included their voices?

One goal of the book was to tell the story of the Gold Rush as a global migration event. People from all over the world came. White Americans, European immigrants, formerly enslaved Black Americans, Indigenous people, Mexican Californios. It was an unprecedented experiment in multiracial democracy.

To understand how America responded, I needed to include some white voices. Someone like William Speer, a Presbyterian missionary, is a good example. Many Christian denominations sent missionaries to evangelize the Chinese and kept detailed records.

One highlight of my research was visiting the Presbyterian Historical Society in Philadelphia. They had boxes of handwritten letters from missionaries. William Speer went to San Francisco in the 1850s and became a champion of the Chinese. He even served as an interpreter in a key murder trial where the California Supreme Court ruled that Chinese people couldn’t testify against white defendants.

The law didn’t specifically mention Chinese, just “Black” and “Indian,” so there was a legal debate about where Chinese fit in the racial hierarchy. Speer, who spoke Cantonese, translated testimony in court and later wrote about it in letters to the Mission Board. His voice helped bring that episode to life.

You traveled to archives, uncovered these stories, and shaped them into a narrative. How did you manage all of that while also working full-time at The New Yorker?

I worked on the book for over four years. My routine was early mornings from 5:30 to 7:30, before getting the kids to school. Weekends too. I started during COVID, when I was working remotely and my kids were in remote school.

In the summer of 2021, we moved to San Francisco for five or six weeks. We rented an Airbnb, and while the kids did school in the afternoons, thanks to the time zone, I used vacation time to visit archives. I went all over Northern California, small historical societies, pine country towns like Truckee, Nevada City. Even places where people vacation are full of history.

I also used the Huntington Library in L.A., which is an amazing place to work. I’d photograph boxes of documents, convert them to PDFs, and organize them for research. I hired Berkeley journalism students and other researchers to help too.

Importantly, I was the first to write this kind of history with full access to digitized records. Thanks to digitization, hundreds of 19th-century newspapers are online now, through sites like Newspapers.com, Ancestry, GenealogyBank, and others. COVID really accelerated university efforts to digitize archives, and that helped enormously.

I remember thinking I’d have to fly to Minnesota for one archive, but they offered to digitize it for $900. I paid, and that was that.

Questions from the audience:

What do you hope Chinese Americans who have respect for the past can take away from this story?

One thing I’ll say is, I think this is a hopeful book. When I look at the Chinese American experience, I see a narrative arc, a story of resilience. Erika and I talk about narrative structure. There's a trope in screenwriting by Robert McKee, some people make fun of it, but it's considered the "bible" of storytelling. It’s the idea of a protagonist who faces a challenge, complications arise, there's tension, and then a climactic resolution. It’s the classic American arc. I see that in the story of Chinese America: a story of persistence and resilience.

In the 1880s, Chinese Americans were actively pushed out of this country, but they kept coming back. In the 1920s and 1930s, the Chinese population grew as native populations in America started to take hold. There’s an arc of persistence. And I’m optimistic because, personally, I tend to be optimistic.

What I want people to take away from this is that difference is hard. Think about your friends, workplaces, or churches. It’s easier to be around people like you. But it takes real effort to make diversity work, whether in your friendships, workplaces, or democracy. We need to keep pushing that boulder up the hill.

You spoke about absences in the archive and places where voices can be found. I wonder if this led you to draw on fictional techniques or other forms of creative writing where nonfiction might not suffice.

I don’t really do that I’m focused on building characters, scenes, and narrative while staying true to the documents. History often involves judgment, and documents can be imperfect, many of them were written by reporters with ugly views of the Chinese. You have to sift through those multiple versions to uncover the best version of the truth.

So much of your research dives into these personal, individual stories. You're excavating all these detailed pieces of people’s lives. But at the same time, you’re building a narrative that spans centuries, covering entire regions or communities. Can you talk a bit about how you zoom in and out like that?

This is my biggest fear as a writer. We're getting into nerdy craft territory now. But when I pitched this book, I had to offer comps, you know, what other books might this be like? And I said, this is going to do for Chinese immigration what The Warmth of Other Suns did for the Great Migration. That book is just incredible, one of the best books of the 21st century. Isabel Wilkerson interviewed 900 people who remembered the Great Migration, but she built the narrative around a few key families. Initially, I aspired to do something similar. I wanted to find a few multigenerational families, like five generations, and use oral histories to tell the story through them.

But it was not possible. I was covering a much longer history. So I wrote each of these chapters as almost their own magazine story. They have their own narrative arc. I tried to build it in a way that built towards something, and the protagonists in the book are the Chinese people as a whole. It follows that narrative spine.

Bonus questions for The Reported Essay

You mentioned you wrote this book while working full-time as an executive editor. What does your job at The New Yorker entail and what do you oversee?

The New Yorker is a relatively small operation, particularly when compared to my previous home, the New York Times. We operate with a very flat organizational structure. There are a few of us who make up the leadership team, and we all wear multiple hats. I'm mostly focused on our coverage of news and politics, but I'm also involved in things like hiring, setting our strategic priorities, advising on investigative stories, and partnering with the product team.

Many writers aspire to publish a piece in The New Yorker, or one day publish a book. Do you have any advice for them?

I firmly believe the best way to become a better writer is to write a lot. I don’t recommend writing a book, or writing a ten-thousand word feature early in your writing career.

What is the difference between writing for print or online at The New Yorker, and how does pitching or the editing process work?

We try to approach the features we publish in a platform-agnostic way. All features—in fact, all of the written pieces we publish—go through a similar rigorous process of editing, copy-editing, and fact-checking. We hold a weekly feature pitch meeting in which we discuss the pitches editors have received from writers––whether it be staff and contributing writers who are already in our stable, or people with outside freelance pitches. Ultimately, David Remnick, the editor of the magazine, signs off on all features we assign.

In the daily edition of the magazine, which is how I like to think of our website and app, we publish a rubric we call The Lede, which is meant to be a daily column on Topic A, or what we think should be Topic A. We also run cultural criticism and commentary. We have other rubrics as well, like the Weekend Essay, or the New Yorker Interview. This isn’t an exhaustive list. The best way for writers to pitch is to read what we publish closely and try to tailor their pitches accordingly.

That was a wonderful article. I am new to your newsletter and enjoyed this first read immensely. I am looking forward to reading more of your stuff. Thank you.