Breaking the Narrative

Kristen Martin on reviewing books and redefining orphan stories

In storytelling, we often learn a version of this classic narrative structure: a character who wants something faces a challenge (inciting incident), which sets them on a journey. Along the way, they encounter obstacles that block them from getting what they want. This leads to a climactic moment—at which point it seems they might never achieve their desired outcome. Then, a resolution. The happy ending.

The familiar story form taps into our empathetic neural systems. Some researchers believe it is an aspect of shared storytelling that gave us an evolutionary advantage. We want to understand how others face challenges or threats so we can prepare ourselves if we ever encounter the same.

Perhaps no other narrative trope feeds off this structure more than the “orphan story.” At its center, we find an abandoned or bereaved child who finds their way in this harsh world and makes meaning out of their journey. If the child is adopted, that adoption often becomes the catalyst for a feel-good ending.

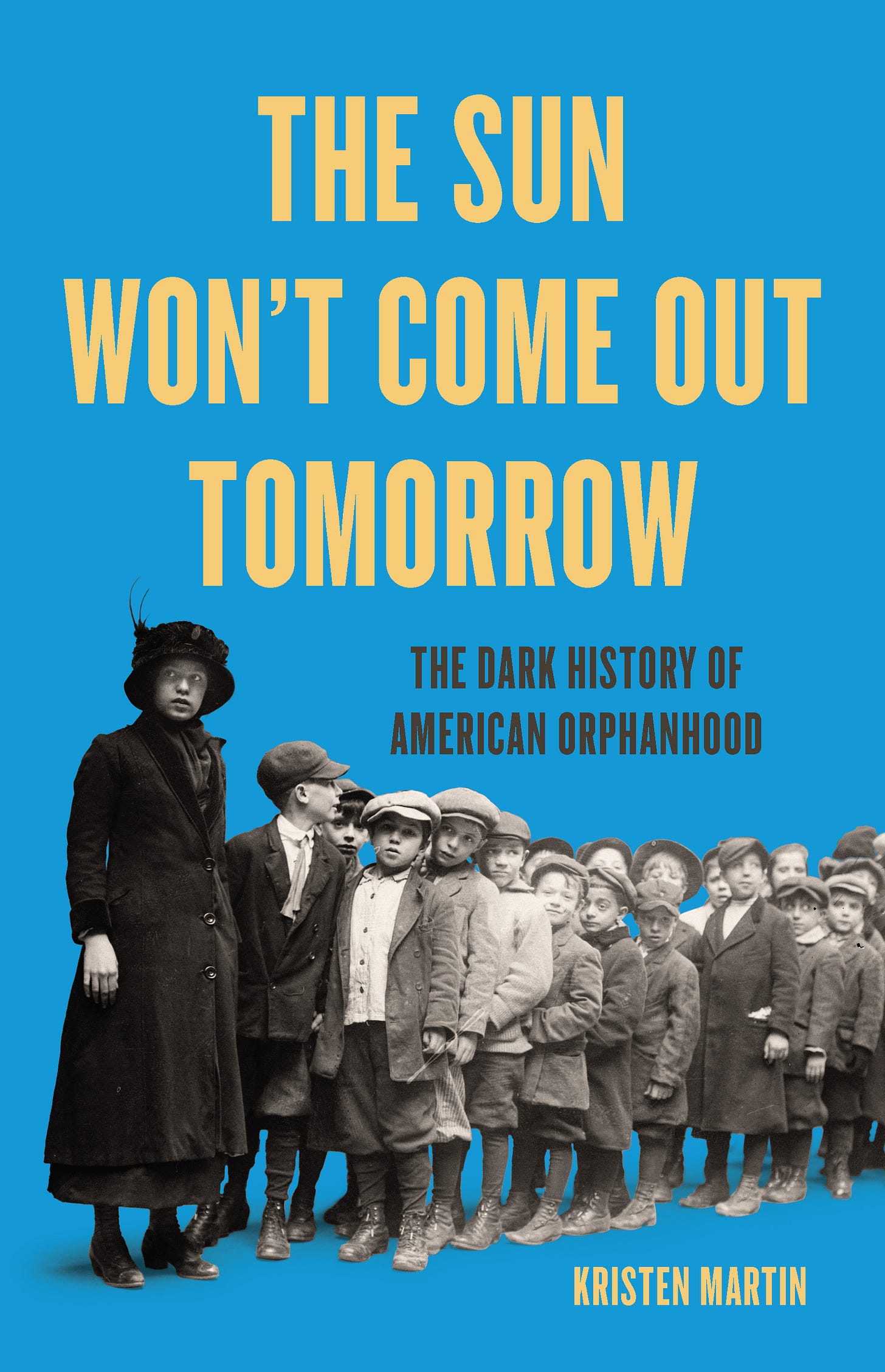

“Once you start looking, it’s everywhere,” said Kristen Martin, author of “The Sun Won’t Come Out Tomorrow: The Dark History of American Orphanhood,” in our interview for today’s Q&A. “I’ve come to see it as a form of propaganda, one that’s emotionally satisfying, narratively useful, and totally normalized.”

Kristen, whose parents died when she was a child, begins her illuminating new book with her personal experience. From there, she blends reported essay-style moments with deep cultural and archival reporting. Kristen delves into the history of orphan trains (which took poor children and often placed them with families who needed farm labor). And she visits the former home of a boarding school notorious for tearing Native American children from their families and forcing them into assimilation. She also brings her cultural criticism lens to the page, dissecting some of the most popular orphan stories we’ve grown up with.

A prolific freelancer and book reviewer herself, Kristen also recently published a piece in The Washington Post: “Uncovering the truth about international adoption,” reviewing two new narrative nonfiction books together: “Daughters of the Bamboo Grove,” by Barbara Demick, and “A Flower Traveled in My Blood,” by Haley Cohen Gilliland, which reveal appalling adoption practices in China and Argentina (*note: both of these journalists will also be featured soon here at The Reported Essay, so stay tuned).

In 2022, I published a narrative nonfiction book, “Somewhere Sisters,” which involved five years of reporting on twins born in Vietnam and separated at birth. One was adopted by a white American family in the Midwest. The other was raised by an aunt and her partner in Vietnam. In alternating historical and contextual chapters, the book also probes adoption practices in Vietnam and worldwide, and the saviorism at the root of so many adoptions.

I came to understand that the reality of adoption is far more uncomfortable and disturbing than society has been led to think. If told honestly, the lived experiences of adoptees will never fit neatly into the story archetypes our culture traditionally promotes or craves.

I was surprised and thankful when Kristen (whom I had never met until our recent talk over Zoom) selected the book in 2022 for NPR’s “Books We Love.” When I read her write-up, I was even more heartened to see that she got it. “On the surface, this sounds like a fairy tale about long-lost family,” Kristen wrote. “But ‘Somewhere Sisters’ is not a fairy tale.”

In recent years, more books and media—including Kristen’s—have continued to upend orphan and adoption tropes. In our Q&A, she talked to me about writing her first book and redefining the narrative. I also asked about her career as a book reviewer. To many, reading books for a living seems like a dream job. Kristen discussed the ups and downs.

Kristen is a writer and critic based in Philadelphia. Her work has appeared in The New York Review of Books, The New York Times Magazine, The Washington Post, The Atlantic, The New Republic, NPR, and elsewhere. She received an MFA in nonfiction writing from Columbia University. She also posts updates about her reviews, writing, and issues she’s following on her Substack, American Orphan.

Our Q&A has been edited for clarity.

I'm curious about your writing journey. I know you said in the book that you worked on the high school newspaper.

I’ve been writing nonfiction for a long time. I was really involved in journalism in high school. The summer before my senior year, I did the Medill Cherubs program at Northwestern, a journalism boot camp for rising seniors.

I loved it. Honestly, most of what I still rely on in journalism, I learned during those six weeks when I was 16. That experience made me realize I didn’t necessarily want to major exclusively in journalism in college. I wanted a broader liberal arts education. I also started gravitating more toward magazine writing rather than daily news. The Cherubs program had us try all kinds of reporting, and it culminated in writing a feature article, which I loved.

I went to the University of Pennsylvania in Philly, and majored in English with a creative writing emphasis. Penn’s undergrad creative writing program is pretty unique; it offers nonfiction workshops in addition to fiction and poetry. I took a class on writing about the arts and pop culture with Anthony DeCurtis, a contributing editor at Rolling Stone, and another class called Writing from Photographs with Paul Hendrickson, who had worked at The Washington Post and written several nonfiction books.

That class with Hendrickson, my senior year, is when I really started writing about my family. Until then, I’d avoided it. I felt like if I brought those stories into a workshop, people would just pity me. I wouldn’t get real feedback, just sympathy, which I’d already heard plenty of after my parents died. But I also wanted to write about them. I was 20 at that point; it had been eight years since my mom died, six since my dad died. I had some distance.

I was also reading books like Joan Didion’s “The Year of Magical Thinking.” Penn had a course where we read the entire body of work of three visiting writers—Didion came when I was a junior. So I was thinking deeply about grief and how to write about it.

The photograph class was a helpful entry point. We wrote short pieces based on photos, starting with family photos. It gave me a way to write about loss in small, manageable scenes. I wrote about a picture from a family vacation in Cape Cod—me, my mom, and my brother building a sandcastle. The photo had boundaries. It didn’t require telling the whole story, just a part of it.

Eventually, I turned those essays into my senior thesis, a collection of personal essays based on photos. Hendrickson supported me through the workshop process. He made sure the focus stayed on the writing.

Did you express that concern to him, or did he just know?

I told him. I remember he called me before my first workshop and we talked about how it would go. He planned how he’d lead the conversation, which I appreciated.

After that, I decided to apply to MFA programs. I took a gap year between college and grad school—worked as a research assistant and babysat. During that year, I applied to MFA programs in nonfiction and also for a Fulbright. I was lucky enough to get both.

The Fulbright was at the University of Gastronomic Sciences in Italy, run by the Slow Food movement. I’d studied Italian since seventh grade and was an Italian minor in college, so I applied. It was a year studying food culture in Italy. I couldn’t turn that down.

I’d worked on a student food magazine at Penn called Penn Appétit, and interned at Philadelphia Magazine working on their food blog. At that point, I was doing some food writing. After the Fulbright, I interned at Saveur magazine and later started my MFA at Columbia. I also did some freelance copyediting for Saveur and Bon Appétit, but I haven’t really written about food since. That year was a bit of a detour, but a great one.

No one could turn that down.

Exactly. So when I applied for MFA programs, I was thinking about writing a memoir. But during my time at Columbia, that shifted into more of an essay collection.

When you first got into journalism, what drew you to it? Was it just an elective, or did you already have a sense of what journalism was?

It was so long ago. I went to a junior-senior high school in Long Island, grades 7 through 12. I joined the junior high newspaper in seventh grade, and that January, my mom died. I honestly don’t remember much from that year, but I think my parents encouraged me to join. A family friend, an English teacher at the school, supervised the paper. It was a way to spend time with her, and I’d always loved reading and writing.

It gave me a way to engage with writing. After my dad died when I was 14, I moved to New Jersey to live with my aunt and started sophomore year at a Catholic school in Edison. They had a student newspaper and a journalism elective. I took that class and began to understand the different types of writing. I started writing cultural criticism—music and book reviews. I somehow convinced my teacher to let me write about obscure emo albums I loved. That’s when I realized I was really interested in entertainment journalism.

Then the Medill program the summer before senior year broadened everything. We did broadcast, radio, scriptwriting, everything. Alumni came to talk about their careers. One of them was at Newsweek writing features, and I thought, that’s what I want to do.

That changed again in college. I wrote for the student paper my freshman year but didn’t stick with it. It was a daily, and if you were on staff, that was your entire life. The building had no windows. You basically lived there. I wanted to try other forms.

In college, I became more interested in creative nonfiction through the writing classes I was taking. I started reading people like David Foster Wallace and exploring different approaches to writing about true things, writing facts in ways that allowed for creativity and experimentation.

You started realizing you could merge your journalism background with creative writing?

Yes, absolutely. During my MFA, I studied with Phillip Lopate, who’s a major figure in the essay world and edited “The Art of the Personal Essay.” That really made me fall in love with the form. It opened up new possibilities for writing about myself in nonlinear ways and playing with structure and form.

I also took classes with Leslie Jamison, who had just started teaching in the program, and Margo Jefferson, who taught an arts writing course. All of that shaped how I approached my work.

Did you know then, especially once you started writing more personal pieces, that you were working toward a book?

Yes, though not the book I eventually published. At the time, I was working on an essay collection. I graduated from Columbia in 2016, and around then I connected with the person who became my agent. She had read a piece I wrote for Lit Hub about Donald Trump’s first campaign, the Central Park Five, and Joan Didion’s essay “Sentimental Journeys.”

She liked it, we had lunch, and I sent her my thesis from Columbia, a collection of essays about my family, grief, and loss. That wasn’t quite what she wanted to represent, but we stayed in touch. Eventually, I signed with her. Her name is Jamie Carr. She was at WME at the time and is now at The Book Group.

We worked on a revised version of the collection and tried to sell it in 2018, but it didn’t go anywhere. I rewrote it again, and we tried to sell it a second time in spring 2020, truly the worst time to try to sell a book. It still didn’t sell.

That was the grief book?

Yes. It was a collection of essays about life, grief, and death. Over time, it had evolved from straightforward personal essays into more of a hybrid—personal narrative mixed with cultural criticism. I had an essay about watching “Six Feet Under” and processing my parents’ deaths, and another about society’s obsession with resilience that critiqued Sheryl Sandberg’s “Option B,” probably one of the worst books I’ve ever read. I’d still love to publish that piece someday, though it’s a bit dated now.

That was the concept of the collection. But looking back, I think I missed the brief window when essay collections were marketable. They had a five-year run, and then unless you had a huge platform or were already famous, they became very difficult to sell. After the first failed attempt to sell the book, my agent and I talked about pivoting to a narrative nonfiction project. Those tend to be easier to sell.

Right. Even when you’re bringing yourself into the story, if there’s reporting and structure, there seems to be more appetite for that.

I think with narrative nonfiction, the appeal shifts from the writing itself to the subject. Readers and publishers focus more on the topic. So I asked myself: If I were to write a reported book, what would it be about?

I started thinking about orphans. At the time, I didn’t know anything about the actual history, but I’d been reflecting on the prevalence of orphan characters in fiction. I’d even written an essay for Catapult about that, beginning with “Harry Potter,” which I read before my parents died. I realized how many orphan protagonists I’d encountered in childhood, but never thought deeply about it until afterward.

Initially, I approached the subject from a cultural criticism lens, which was more familiar to me. But after the second failed attempt to sell the essay collection in 2020, I shifted focus more seriously to the orphans project. As I started researching, I was stunned by how strange and unfamiliar the real history was, even to me, as someone who had been orphaned.

So you were able to pitch it as something that began with your story and expanded outward?

Yes. The proposal changed a lot over time. When I first pitched it to my agent, it was heavy on cultural criticism. Then, based on her feedback, I revised it to emphasize social history and reporting. That’s how we eventually sold it. The overview and structure were similar to what’s in the final book, but at first, the cultural criticism was mostly in the introduction.

Ironically, once editors started weighing in, they all wanted more cultural criticism. So I restructured the book so that each section, tracking a different historical period, opened with a chapter of cultural analysis.

As I worked on the book, it also became less about me. My own experience just didn’t reflect the broader history. I was surprised toward the end of the process when I looked at the draft of the index and saw my parents’ names listed, and that they only appeared on six pages or so. Originally, I thought the book would center much more on my own story, but over time, that receded.

You’ve also done a lot of book reviews and cultural criticism. How does all that reading shape how you write a book? Do you think about how your voice fits into the nonfiction landscape?

Definitely, and it can be overwhelming. It’s easy to lose your mind over it.

A lot of writers avoid reading books similar to their own because it sets up impossible comparisons. Or they worry they’ll accidentally echo something.

Totally. One challenge I faced is that so many narrative nonfiction books, especially those dealing with history or structural injustice, focus on one central story. A single person or family becomes the emotional anchor for the reader. I couldn’t do that, because my book spans a huge time period, from the 1800s to today.

I had to figure out how to weave in characters to bring the history to life. That was something my agent and editors focused on with me. We asked: “How can we make the history feel lived-in and human?” I tried, though it’s not my natural strength. I tend to think in bigger-picture synthesis rather than tight, narrative storytelling.

I loved how you used the archives, especially letters you discovered, which spoke about children on the orphan trains.

Yes. Most of the people I initially hoped to interview from older eras were no longer alive. I thought maybe I could find someone who had ridden the orphan trains, but anyone still alive would be over a hundred. So that was impossible.

Instead, I turned to the archives. Finding those letters was huge. I also got copies of books put out by a group called the Orphan Train Heritage Society of America. It was a historical association formed in the 1980s that started holding reunions for former riders. Many of them had believed their experience was unique, they didn’t know it was part of a massive system run by multiple charities.

I have six volumes of their first-person accounts, sort of written oral histories. There was also a PBS “American Experience” documentary from 1994 that I tracked down on DVD. I got some stories from that, too. I had to be creative in finding ways to bring these stories to life, especially when direct interviews weren’t possible.

I wonder if you could talk a little about the process of going through the archives. You also offered reflection in moments. There are scenes where you're clearly moved and disturbed, and you share that, which I think is helpful.

I found out early in my research, through library databases, that the New-York Historical Society had the papers for the Children’s Aid Society—one of the main orphan train organizations—and the New York Foundling Hospital, a smaller Catholic organization doing similar work. I made appointments to access those archives.

When you're using archives at places like that, especially since I had to travel from Philly to New York, your time is limited, maybe two or three days to go through material. So I had to figure out how to capture a lot without lingering over every letter or paper. I asked ahead of time if I could take photos, and they said yes. I downloaded the Dropbox app and scanned everything as PDFs with my phone. I’d quickly open pages, scan them, move on. Of course, I paused when something caught my eye, just to understand what I was looking at. Even though things were organized and there was a finding aid, the descriptions were minimal compared to what was actually in the folders.

I started with the annual reports rather than the letters. That’s where I saw how the Children’s Aid Society described their own work. It was essentially propaganda. One early report claimed that if they weren’t doing this work, New York would be ruined by poor children and families flooding the streets. There was so much xenophobia and fear-mongering about European immigrants, how it was essential to get their kids out and into “good Christian homes” elsewhere.

Then I started reading the letters and saw how terrible the record-keeping was—often just two lines about each child sent west. For decades, there was little to no information kept. That contrast, the polished narrative of the reports versus the reality in the archives, was really striking.

With the Foundling Hospital, what really got to me were the forms filled out by people who had been sent west as children, now in their 70s or 80s, asking for any information about themselves. They didn’t know their birth years, parents’ names, nothing. That reminded me of issues adoptees face today, trying to access original birth certificates. The secrecy enforced by the Foundling Hospital was extreme. I saw that again in legal documents in the collection.

They had never even been told anything, right? Just sort of left there?

Exactly. So I also found myself thinking about what it meant for me to be reading those letters. If they were addressed to parents, why were they still in the organization’s files? Clearly the organizations kept copies, or the letters were never sent. Once I had the PDFs, I sorted and reviewed them alongside journal articles and historical books written by scholars who had also gone through some of these archives.

In terms of how I decided to bring emotion into the writing, I experimented with different ways of approaching the material. I was really conscious of not sounding dry or academic, because I'm not a trained historian. And because I already had a personal angle, I felt I had the flexibility to include my reactions. My voice helped me bring some life and tone into the history.

When you go into places like the Native American boarding school, there’s this powerful sense of place. It reminded me of Clint Smith’s book “How the Word Is Passed.” He visits historical sites, but uses those visits as a framework to bring in reporting, research, and reflection. It’s effective.

I wanted to do something similar in that chapter about the Native American boarding schools. I did archival research for that too, less of it made it into the book, but I wanted to explore the tension between how the school and town tell the story versus the actual experiences of the children.

That same approach informed how I wrote the orphan train sections, interrogating the official narratives from the organizations, and then revealing the consequences and harm. The deeper I got, the more I saw the same themes repeating: racism, classism, religious control. It became a book about poverty and fear, and how the U.S. defines which families “deserve” to stay together.

I think there’s this idea we’re taught that narrative must follow one person or one family. That’s what I was taught too: find the person, follow the journey. But what happens when you can’t do that?

Exactly. Readers naturally gravitate toward learning through a single representative story, it’s easier to follow. I was taught that too, even back in high school: find the “blade of grass” that represents the whole. It’s something I’ve taught in my own writing classes. But in this project, I couldn’t do that. So instead, I had to find multiple stories—fragments, voices, documents—that could illustrate the bigger picture.

I hadn’t come across many of these histories until your book.

I think that even the parts of family separation we are familiar with, like international adoption or private infant adoption, have their own layered histories. But they’re relatively recent. Private infant adoption, as we understand it now, really took off in the mid-20th century, especially during the Baby Scoop Era in the ‘50s and ‘60s. And international adoption is even more recent. It’s also declined significantly in recent years, which I think is a good thing.

What struck me is how many patterns repeat. The same justifications, the same public-relations-style narratives—the way these organizations or governments frame their work. Even when you were describing the unanswered letters, the files tucked away, the mothers being coerced—it all felt so familiar. It echoed things I’ve come across when reporting in Vietnam, or hearing about recent separations at the border.

Exactly. As I kept digging, I realized I was writing a book about American attitudes toward poverty, and how those attitudes intersect with race, class, immigration, and religion. It’s about who we believe deserves to have a family. The same themes kept resurfacing: the idea of the “deserving poor” versus the “undeserving,” who gets to parent, who gets support. These ideas haven’t gone away. They just evolve.

And now, in the moment we’re living through—with families being separated at the border, ICE raids, children left behind—it’s overwhelming to even track all of it. How do you see the conversation your book is having intersecting with what’s happening right now?

It’s all part of the same pattern. Nothing has changed, really. The mechanisms and justifications shift slightly, but the core ideas remain. There’s a book by scholar Laura Briggs called “Taking Children” that I drew from. It’s about the long history of governments forcibly taking children. In the introduction, she mentions Hillary Clinton tweeting in 2018 that family separations under Trump were “un-American.” And Briggs says, no, they’re actually deeply American. The U.S. has been separating families since before it was the U.S.

Activist Joyce McMillan, who I interview in my book, has this line: “They separate children at the border of Harlem too.” It’s true. Family separation is daily, mundane, in many neighborhoods. It’s just that we notice it more when it happens in politically explosive ways.

There was a story just recently in Florida: a teenage boy placed in foster care was taken by ICE from his foster family. There’s now a whole category of foster care just for children whose parents were detained or deported. We still haven’t reunited over a thousand families from the first Trump administration. And I wouldn’t be surprised if some of those kids have since been adopted by American families.

Your book reminds us how entrenched these romanticized narratives of orphanhood are.

It’s everywhere, especially in kids’ media. I hadn’t even realized “Lilo & Stitch” is an orphan story until the recent live-action remake. I missed that movie when it first came out, but now I’m seeing it everywhere. And from what I’ve read, the remake made those themes even more overt.

I think most people consuming these stories don’t even notice it. They’re not asking why orphan characters show up so often, or what it signals. But once you start looking, it’s everywhere. I’ve come to see it as a form of propaganda, one that’s emotionally satisfying, narratively useful, and totally normalized. That realization came slowly, over the past decade of thinking about this.

And because it’s so common, it’s hard to push back. I talk about this in the book’s conclusion, how I’d track book deals for research. At one point, I mention 50 orphan-themed book deals. But it’s more like 100 now. I see them weekly in Publishers Marketplace. Just this week, I spotted two more. It’s such an easy trope, it simplifies storytelling and tugs at heartstrings. And we keep recycling it.

I kept thinking about how much material you must’ve had. How did you decide what to include, how to structure it, and what to leave out? Because with research-heavy work like this, the refinement process is huge.

That’s always the question. I found that the structure that made the most sense was to go linearly through time. Even that was tricky, because the periods overlap a lot. But once I started really digging into the history, from the 1800s to now, I saw three distinct philosophies around caring for “dependent children,” or what society labeled as orphans.

The first era was orphanages. The second was the orphan train movement. And the third, and still current, is foster care. The overlap is messy: orphanages ran well into the 1940s; orphan trains operated from the 1850s to 1929; and foster care, as we know it, started around the 1920s and continues today.

So the complication was: how do I track the philosophical shifts through these overlapping systems? Once I had those three eras laid out, I could figure out how to organize the chapters. Within each section, I included relevant cultural representations, like Little Orphan Annie and those strange novels about orphan trains, and then more modern portrayals of foster care on TV, where shows often sidestep or sanitize the reality.

So you laid out the structure, and chronology obviously helped. That’s often a good starting rule.

Yes, and I’ve found that when you go against chronology in historical nonfiction, it often comes back to bite you. I’ve read plenty of books that try to break away from linear structure, and what happens is you end up revisiting the same time periods over and over. It gets repetitive. Even with my overlapping time periods, I still repeated some events. But overall, it made the most sense to go chronologically.

I think it’s especially tough when writers are juggling multiple timelines, switching back and forth by chapter. It can get confusing, especially when there’s overlap, which is often why those timelines are being paired to begin with. But if I’m reading it quickly for a review, I can follow. Your average reader might pick the book up once a week and forget where they were. If I find it confusing while reading closely, it’s a red flag.

Just to pivot to book reviews: I’m curious: how often are you reviewing books? How many do you read? What’s your process?

I start a lot of books and don’t finish them. That’s just part of the job. I’m constantly reading and pitching reviews. Usually I pitch two to three months before publication. By the time I pitch, I’ve read at least a quarter of the book, enough to know I want to keep going and that I have something to say.

Sometimes I’ve read the whole thing because I couldn’t stop. Sometimes just half, to get a strong sense of the arc and how it develops. For some outlets, your review is more like an essay with a clear argument. For others, it’s more straightforward, which is easier to pitch.

Right now, I have four or five reviews due this month, one of them covers two books. That’s a lot. But freelancing’s unpredictable. You pitch and don’t know what will get picked up. Sometimes everything hits at once.

That’s a heavy load. You’re reading to assess potential, not just for fun.

Exactly. I read a lot just to figure out if I want to review something. I try to give books more than one chapter, but sometimes you know early on if it’s not for you.

I find it really rewarding. But it’s not paid nearly well enough. And cultural critics in general, book critics especially, aren’t treated like journalists. Our work is undervalued, even though it is journalism.

I’m part of the Freelance Solidarity Project through the National Writers Union. We have a cultural critics working group that’s done panels, campaigns, and advocacy around this. We document how many hours a single piece takes, because it’s a lot. Reading, re-reading, researching the writer and context. It’s time-consuming. But I genuinely love reading nonfiction. It’s what drew me to journalism in the first place: learning deeply about all kinds of topics without needing to become an expert in just one.

That’s so true. But I imagine it’s getting harder now, even for you, as someone with experience.

It is. I’ve been doing freelance criticism regularly for about six years. And it’s gotten tougher. Outlets are folding or scaling back reviews. Even The New York Times is putting out way more listicles than in-depth reviews.

And it’s hard to pitch longform. I love to write 3,000-word essays on books. But it’s nearly impossible to get that assigned. Most reviews are 800 to 1,000 words. Some outlets, like The Nation or New Republic, give you 1,700 words, but they don’t pay that well. So it’s a constant balance.

Yeah, and so many book review sections have just cut back or disappeared altogether.

Exactly. And it's a problem across all of cultural criticism. Film, music, books. The entire sphere is dealing with the same challenges.

Even if you're writing a book, there's only so many places that will actually review it, if they even still run reviews.

Yes. That was definitely on my mind while my own book was coming out. As a critic, I get dozens of pitches every week from publicists. And there’s just not enough time. Which leads me to a hot take: too many books are published. It’s just the reality. Everyone’s stretched so thin.

And being on the other side now, publishing your own book, did you go into it already knowing how difficult it would be to get visibility?

Oh, 100 percent. I went in knowing how it works. Every publishing season, the imprint decides which titles they’re going to push in terms of publicity and marketing. And usually, it’s not your book. I knew that going in. You also have to forget about bestseller lists, especially for nonfiction. Those lists are basically preordained based on what titles get big marketing budgets, often celebrity memoirs or political books. And let’s be honest, many of those political books are awful.

And also, the publicity game has changed a lot in recent years. It used to be that there were certain steps you could take to get a review in The New York Times or to land a spot on a particular radio or TV show. But now, those things aren’t guarantees, and even if you get them, they don’t guarantee a book’s success anymore. Everything has changed. So knowing how messed up the industry is going in really helped me temper my expectations. Of course, you still hope for breakthroughs or good luck here and there. I felt very lucky to get a wonderful review in The Washington Post. But yeah, it’s tough.

I guess in the end, when you think about why write a book at all, people ask themselves that question, it’s different for everyone. But you really do have to go into it knowing that even people who seem like they have a platform don’t always have books that take off.

There’s a difference between how a book hits critically—I understand that as a critic—and how it hits with general readers, which feels like a total mystery to me. People ask all the time: “Do book reviews help sell books?” And my answer is no. I don’t think many people read reviews, unfortunately.

So it’s tough to answer the question, why write the book? It’s been a roller coaster for me the past six months. But I’ve been gratified by notes from readers with family connections to the history I wrote about, who say the book changed how they understand their own lives. That’s been very meaningful. Also, the book has resonated strongly with adoptees, which surprised me a bit because I’m not an adoptee or a foster care alum myself.

To hear them say, “I see myself in this,” or that they appreciate how I write about these myths because they also affect adoptees, that’s been really important.

Wow, such an in-depth interview with great insights. I love how she gets into granular detail about her evolution as a writer and the evolution of her book. As a freelance essayist who has also written book reviews, I agree with her points about the reviewing process. Enjoyed this detailed post.

Thank you. The author’s journey on revealing the layers to adoption is a compelling one. It also begs the question, do we really want to know? Do orphans really want to know?